[dropcap]A[/dropcap] growing interest in Burmese contemporary art is providing new opportunities for artists to gain international exposure, while the lifting of censorship laws in 2012 has enabled local galleries to exhibit avant-garde works that previously wouldn’t have seen the light of day. However, developing a thriving contemporary art scene in Burma will take time because market prices remain undervalued, training in contemporary art is non-existent and the number of fakes being produced is on the rise.

The National Museum in Rangoon was established in 1952 and has twice been relocated to bigger sites. It currently occupies a five-storey building and has two large art galleries.

The owner of Pansodan Gallery, Aung Soe Min, described the museum’s fine arts collection as “very good” – albeit somewhat dated. During the 1950s and early 1960s, its gallery director purchased the works of famous artists such as U Ngwe Gaing from the family estate after the artist passed away.

“The director made some really good decisions, but after General Ne Win came to power [in 1962], the gallery wasn’t in a position to make decisions, so the collecting stopped. It hasn’t really resumed and there’s not much understanding of contemporary art,” Aung Soe Min said.

Bizarrely, up until a decade or so ago, Burmese people themselves were unwelcome in private galleries. The sought-after clientele were foreigners, who were assumed to possess both an appreciation for art and deeper pockets.

“Gallery owners just couldn’t believe that a Burmese person would actually want to buy a painting. I remember going to a gallery about 13 years ago and when I asked the price of a painting, I was simply told, ‘Never mind.’ I couldn’t understand it,” he said.

Undervalued art and weak infrastructure

“Even if we exclude China and India, where prices are stratospheric, I don’t think there’s any other country in Asia where it’s possible to buy a large canvas by a top artist for under US$15,000 or $20,000,” said Gill Pattison, the owner and curator of The Strand’s River Gallery and River Gallery II.

According to Aung Soe Min, fine art prices have trebled over the past five years, which he attributes to the rise in the number of foreigners visiting the once-isolated country and a growing interest among local collectors. However, with an average inflation rate of 5 percent since 1999 and the cost of living spiraling ever upwards, the vast majority of Burma’s artists have yet to find any breathing space.

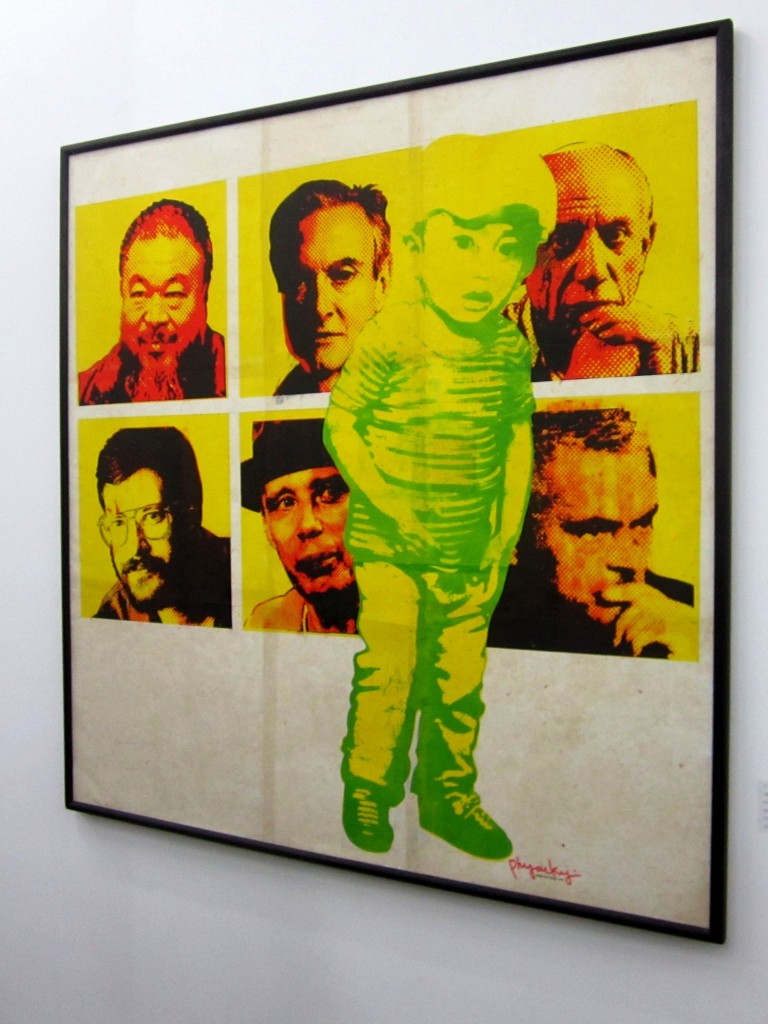

Phyoe Kyi, 38, has struggled to make a living as an artist for almost 20 years, despite having cultivated a strong reputation in mixed media. He is among the only artists in Burma who works with silkscreen: one such collection on Shan paper and canvas was featured at ts1’s opening exhibition in April (the gallery is owned by Ivan Pun and has quickly established itself as one of the city’s edgiest spaces). However Phyoe Kyi, who lives in Taunggyi, Shan State, told DVB that it’s almost impossible to compare prices in Burma with other countries in the region because local art dealers are such a mixed bunch: Some are kind and fair while others are brazenly profit-driven.

“In 2001, a dealer in Yangon [Rangoon] bought one of my paintings for just $15 and then sold it to a collector abroad for $600,” Phyoe Kyi said. “During that whole year, I sold more than a hundred paintings but I ended up with just $2,000 – which was a whole lot less than the dealer.”

Pattinson added that such buying practices makes it difficult for artists to learn how to properly market and sell themselves.

“Like every education system in Myanmar, our art courses aren’t so good.”

“Artists have no opportunity to learn about the business side of things, such as how to package themselves as artists or the type of galleries they target. That means that artists either pick it up by osmosis or they don’t. It’s very difficult for them because most aren’t business orientated and don’t want to be,” said Pattison.

The country’s only two art schools – the University of Culture in Mandalay and the State Fine Arts School in Rangoon – are under-resourced and offer no instruction in art career management. Admissions to the State Fine Arts School are few: Only around 15 graduate each year. Most of the teachers are self-taught and classes are limited to watercolour, acrylic and oil painting.

“Students get a very thorough grounding in depicting Myanmar’s [Burma’s] heritage items and religious icons – they all come out knowing very well how to depict Budddhas, temples and traditional motifs,” Ms Pattison said.

“Like every education system in Myanmar, our art courses aren’t so good,” Aung Soe Min said with a shrug.

Another factor that has traditionally worked against artists’ ability to make a living is the fact that private art collections were rarely considered a status symbol among the Burmese elite. And during the decades Burma spent under military rule, it wasn’t unknown for a high-up official to acquire a piece of artwork gratis.

“There was nothing that could be done to prevent it because these kinds of people were all powerful,” Aung Soe Min said.

For the most part, preferences remain strongly in favour of more traditional themes, such as serene landscapes or the well known combination of monks, parasols and pagodas. Paintings which contain a nationalistic element are also popular, Aung Soe Min said. Fortunately, he’s noticed a significant increase in the number of local collectors in recent years, although most remain unfamiliar with contemporary art.

“The art market was absolutely tiny in the days before reforms – things have certainly improved. But while we’re now seeing a lot of people turning up to exhibitions, I don’t think there’s been a significant rise in sales,” said Ms Pattison.

Predicting market trends

Pundits in the art world predict that Burma’s art market is poised to follow in the footsteps of China, whose contemporary art market took off in the 1990s following a wave of economic reforms that began in the late seventies. Today, China’s top contemporary artists can earn tens of millions of dollars for a single painting.

“Finally, curators from major museums all over the world are coming and meeting with Burmese artists – this is the first step in increasing market value,” said Nathalie Johnston, gallery director of ts1.

Ms Johnston, who wrote a thesis on performance art in Burma at the Sothebys Institute of Art in Singapore, described art valuation as a “strange and nebulous market”. Factors often taken into consideration include an artist’s reputation in terms of who has bought their work, where it has been exhibited, and who has written about it.

“I’m sure that there will soon be a rise in sale and market value in Burmese contemporary art. In fact I think there already is – it’s night and day if we look back five years,” she said.

Another means of gauging market value is simple supply and demand. In Burma, supply is limited because “the number of accomplished artists who have that magic combination of creativity and technical skills is small,” Ms Pattison explained.

She said that investing in Burmese contemporary art could become a good portfolio in years to come.

“There are maybe 10 or 12 Burmese artists who are really special and in a league of their own, and their work is definitely undervalued. Look at this big canvas by Zaw Win Pe, for example [which costs $11,000]. He is one the most original and accomplished artists in Burma and I’m quite sure he’ll be featured in art history books a hundred years from now,” she said.

The end of censorship?

The lifting of harsh censorship laws following the transition to quasi-civilian rule in 2011 has given artists greater scope to exhibit their work, which is the natural precursor to making a sale. During military rule, exhibitions were screened by censorship boards prior to public openings. Artwork that was deemed unacceptable to authorities – such as nudes – were simply confiscated.

“Even during the socialist era, there was a lot of good art being created – many artists kept on doing what they wanted to do. But the end product would hang on someone’s wall at home – it would never be shown in public,” said Aung Soe Min.

Ms Pattison used to keep certain paintings in the gallery’s back room: They were reserved for trusted customers rather than public display. “The types of paintings I’d keep in the back room included nudes, those which were overtly critical of the regime or showed great poverty and desperation,” she said.

When Ms Pattison launched River Gallery II in late 2013, she selected a fiberglass installation (the first of its kind in Burma) that would without a doubt have fallen afoul of censorship laws. Aung Ko’s “Ko Swe” or “Golden Men” featured half a dozen naked men in a loose circle of various poses, with some pointing golden pistols. In the centre lay a man whose full frontal genitalia was impossible to ignore.

“It certainly tested the boundaries of nudity – but no one fainted,” Pattison said with a laugh.

However, there are worrying signs of backsliding in newfound artistic freedoms. Johnston said that members of the Special Branch Police visited ts1 prior to a performance art exhibition last month.

“I told them there would be ten women performing for 15 minutes each – but I didn’t know what they would be doing – the point of performance art is that you’re not supposed to know,” she said.

“I’m really shocked and depressed about what’s happening; that Burma could be returning to the old ways,” Johnston added.

Fakes on the rise

Unfortunately, as Burmese artists start to gain the financial recognition they deserve, others keen to cash in their success are producing fakes. According to Ms Pattison, it’s a phenomenon that’s becoming increasingly common.

“A lot of the big names are fakes. It happens all the time and there are no efforts to stop it,” Aung Soe Min said.

One source told DVB that there are small stables of artists in Rangoon employed to copy artwork by well known names.

For the meantime at least, the practice is far less rampant than in China and Vietnam – Johnston told DVB that there is a city in southern China with several factories producing copy-cat works.

Tun Win Aung, 39, is one of Burma’s most celebrated contemporary artists. His solo and collaborative work with his wife Wah Nu have been exhibited everywhere from Tel Aviv to Brisbane, as well as New York’s Guggenheim Museum.

“Wah Nu and I have seen other works that are very similar to ours. There have been times that we were absolutely sure that they were copied from our originals. While some people are simply doing it for inspiration, others are attempting to copy the works of late artists and that’s a big problem,” he said.

Tun Win Aung said that fakes are sold at Bogyoke Market as well as a handful of galleries in Rangoon.

“Be aware of the artists that are being shown in reputable galleries and then if you see something that’s a bit of a bargain, you should probably assume that you are getting what you paid for,” cautioned Ms Pattison.