Burma’s President Thein Sein meets with an ethnic delegation tomorrow for talks that could shape the country’s future. However, several important issues remain unresolved or uncertain.

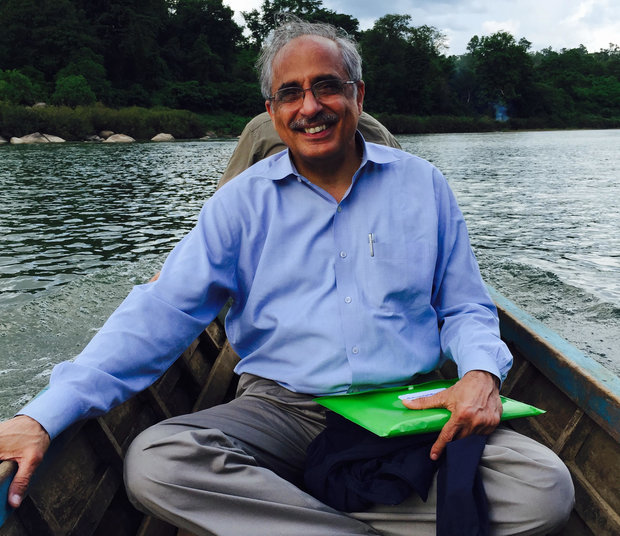

DVB speaks with Vijay Nambiar, the Special Adviser on Myanmar to the UN Secretary-General, who has sat in as an official observer on ceasefire talks, and asks him his opinions on whether the much-anticipated Nationwide Ceasefire agreement, or NCA, will ultimately prove successful.

Q: You have observed the peace talks first hand. What is your overall assessment?

A: We may be reaching the end of the first step towards solidifying ceasefires and the beginning of a comprehensive political dialogue that may set a path to genuine peace in Myanmar [Burma] after decades of civil war … a civil war that has cost numerous lives, forced hundreds of thousands into leaving their homes and robbed many generations of the opportunities for improved health, education and livelihoods. These are not the first ceasefires to be negotiated in Myanmar. There is a history of failed efforts and broken promises. But I do believe that there exists today a genuine will to negotiate and the beginnings of an effort to address political and economic grievances. Obviously this will not be easy. I am sure we will face many setbacks along the way. This is true of every peace process around the world. However, it would be a mistake to undervalue the significance of having an ongoing process where stakeholders are able to meet and talk. We must realise that the world is changing rapidly and Myanmar too is undergoing huge transitions and transformations. We must be willing to learn the lessons that history teaches us. But we must also learn not to be bogged down by the past and find new solutions for the future. I believe that such an approach can bring solutions previously unavailable to us.

I feel very honored to have been invited, on behalf of the United Nations and the Secretary-General, to observe the peace talks together with China during the last few years. I have also been privileged to be invited by the government and the Ethnic Armed Organisations to observe several summits and conferences in the course of the peace and reconciliation process. As an observer, I would like to say that the patience and perseverance shown by all sides has been truly impressive. Clearly the issues involved in the negotiations, not only between the two sides across the table, but even within the concerned parties themselves are deeply complex. Over the past months, the UPWC [Union Peace-making Work Committee] and NCCT [Nationwide Ceasefire coordination Team] have pursued a very nuanced and carefully crafted path. It would be difficult to comprehend these complexities without seeing, at first hand, the detailed nature of the consultations at many different levels through the negotiations and the amount of detailed thinking and technical work that has gone into every stage. I truly feel the way this homegrown process has evolved is unusual. While there is little doubt of the ownership of the process, we can also see the responsibility that it implies towards everyone involved.

There are questions raised, at times, as to why the UN has not tried to assume a more direct mediatory role over the process or take on bigger responsibilities. I have three comments. First, any such role by an outside party requires prior agreement by the conflicting parties, not only in principle but also in respect of critical details. A comfort level has to develop over time. Second, any negotiation that can be handled between the parties themselves is better handled directly. In my view, it is the affected parties that are the only ones who have the potential to truly understand both the complexities and historical weight of the various issues affecting each side and to be able to make decisions on behalf of their people that can carry conviction and legitimacy. Third, the more time I spend observing and dialoguing with the two sides, the more convinced I am that there are critical details of the ground situation that require a understanding of context and fluency in local languages that can only come from within. Ultimately, it is only such direct contact that can build trust and confidence on which any sustainable peace can be built. Outsiders can provide only a supporting environment. This we are prepared to do. But the trust must come from within.

Q: The talks have lasted eighteen months, but that’s not all that long relative to ceasefire negotiations held in other countries around the world. What are the elements you have observed that have allowed this process to consistently move forward over the period since 2013?

A: The ceasefire process has lasted longer than 18 months. By the time we came in as observers to the process in early 2013, many EAOs had already signed bilateral ceasefires with the government. This process has been going on since 2011. The process that started 20 months ago was to achieve a nationwide ceasefire that was one of the steps towards the commencement of a political dialogue. The peace process itself has not lasted long from an international perspective and everyone involved seems aware that it is only beginning. But, the main reason, I believe, the process continues to move forward is that there is a genuine will on the part of the people of Myanmar to have peace. I think the negotiating parties on both sides recognize this. I also think that the government has made an important concession by guaranteeing that EAOs may hold on to their arms until such time as a political settlement has been reached. The commitment to build a democratic federal union is also unprecedented in addition to agreements to form implementing mechanisms to monitor ceasefires as well as initiating a political dialogue. I have been deeply impressed by the strong determination and commitment shown by many leaders on both sides of the table in their effort to overcome the mistrust and grievances of the past. And even where the mistrust continues, there seems to be a strategic recognition that only by moving forward with the process, conditions can be improved and a sustainable basis for peace on the ground created.

Q: What are the consequences if the nationwide ceasefire agreement falls through – if a lasting agreement fails?

A: I shall not venture to speculate in that direction. But I do believe that many commitments have already been made and it is our hope that these will be respected and built upon.

Q: At the opening of the Lawkheela ethnic summit on 2 June this year, you said, ‘We all know there is no military solution to the conflict in Myanmar. The only way forward is through a political dialogue that will give everyone a voice and space to work for their political rights.’ Could you elaborate on what you meant by ‘space to work for their political rights’? Do you still stand by this?

A: A military solution is never a good solution. It brings continued suffering and misery. It is rarely a situation where people are enabled to work together for a fair and sustainable future for all the parties involved. I believe that the people on either side who are pushing for a military solution, or who believe that a civil war can be ‘won’ are misguided. I also believe that this is not the time for grandstanding and threats from either side.

Q: The current state of play appears to show an impasse on the issue of whether to include six ethnic armed groups – the Kokang MNDAA and its allies – in the NCA. Where do you stand on this issue?

A: As an observer to the process, we do not wish to take a stand on particular issues. We continue our close dialogue with both parties supporting them to find ways to move forward for mutual benefit and in accordance with the values that guide the United Nations. While the process is ongoing we encourage all parties to remember and to respect the conflict affected communities on the ground.

[related]

Q: The Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO) is remaining adamant that the six excluded EAOs be re-admitted to the NCA. Can there be an NCA without the KIO? Do you have a specific message for the KIO leadership?

A: First, just to clarify that the KIO is not one of the six groups you mention (TNLA, AA, Kokang, ANC, LDU and WNO). And as I just said, this is not for the UN to decide. We have had very constructive conversations with the KIO as well throughout this process. We trust that their leaders are committed to peace and finding positive ways to move forward. Personally, I would like to say that it has been a privilege for me to have been able to come in such close contact with the leaders in Kachin state and to be acquainted with its people. My visits to Kachin, including to the KIO headquarters in Laiza have been inspiring. They have helped me better understand the many challenges the people face. The UN will continue to work for the de-escalation of conflict and for improved humanitarian access in Kachin. Most recently, we have been concerned for the IDPs in Sumprabum. However, throughout the process, we have deliberately kept a low profile and tried to talk to the people directly rather than through the media. This is not a process that belongs to either the UN or the international community. It is the people of Myanmar who own both the process and its outcome. For the UN, our responsibility and commitment will be to support their effort, not to create a parallel process. This has been the mantra of our engagement. As I have said privately on many occasions, in many complex situations around the world, you can choose either to be seen to be doing good or actually do some good. It is hard to do both together.

Q: Is there a fear that the most important elements of a future peace are being postponed in an attempt to rush through the NCA before the election?

A: Elections pose challenges for many peace processes around the world. At the same time, free and fair elections are a crucial milestone for any democracy. The general election in Myanmar is a reality and a necessity. Nobody involved in this process has ever believed that the contours of a future peace will be entirely settled before the elections. But for any progress to be made, the drawing up of some preliminary framework and building of a prior commitment is necessary. My hope has always been that the NCA process could open up greater space for the ethnic groups and communities to be included in the larger national transformation in a more meaningful manner and to a more substantial degree. There are great resources and much capacity within the ethnic communities in Myanmar. This is something I have seen at first hand. It is my hope and expectation that many of these individuals and groups are able to take on larger national roles in the future and represent not only their own constituencies, but bring their values to all the peoples of Myanmar. I sincerely believe that only when the peoples of all ethnicities and religions in the country stand together to build a federal union and when such a genuine commitment to power sharing is reflected in the constitution, that democracy can become a sustainable project for Myanmar.

Q: Does the process as it stands hinge on the re-election of the Thein Sein administration?

A: No process relies on the election or re-election of a single individual. I believe the president has made a great contribution by defining peace as a priority for his administration and his public commitment to establish a democratic and federal union based on the outcome of a political dialogue is encouraging. I also appreciate his stated commitment to resolve all conflicts though political means and not militarily. The international community has high hopes and expectations that any administration in Myanmar will make peace and reconciliation its highest national priority. What has already been agreed can become an important benchmark upon which any new government can build.

Q: You said ‘real trust can only be established during a period of political dialogue’, and that ethnic groups must take a ‘leap of faith’. Do you expect a ceasefire to be adhered to by groups that do not trust each other not to break it?

A: No ceasefire agreement is likely to be perfect. Indeed, during the initial stage of its operation, tensions could even tend to escalate. That does not necessarily mean that a ceasefire has failed. Instead this initial period should be used as an opportunity to flush out spoilers who may wish to continue conflict, identify hotspots and use the situation to design working mechanisms for monitoring that may help prevent future skirmishes and make clear to all involved as to who is actually responsible for fresh breaches of the agreement. Furthermore, processes are likely to be set up for leaders to come quickly to the negotiating table when fresh skirmishes happen. This is crucial to prevent escalation. This is what we mean by making a ‘leap of faith’. Apart from its symbolic value, having an agreement will impart a sense of responsibility and obligation to abide by promises made. We know that many ceasefires fail. But it is rarer still for peace to come about without a ceasefire. As such, a ceasefire agreement is a necessary step along the way. We need to be realistic in our expectations but unless we work hard to enlist the help and support of the people on the ground, our peace efforts are unlikely to succeed.

Q: You asked ethnic groups to make concessions when you met with leaders at the Lawkheela summit in June. What were they? And have the ethnic groups been willing to make them?

A: We have, from the start, appealed to both sides to make compromises. During the last three years we have had many meetings with government, army, parliament and EAOs together and individually, and my message has been that concessions will need to be made on all sides, not on one side alone. As an observer at the meetings, I am also aware that both sides have, indeed, made many concessions and found creative solutions to many points of difference that have emerged during the negotiation process. In any such process, the difficult issues are normally left to the end. Our message to parties now is that they recognise that the best does not become the enemy of the good. It is the responsibility of all sides to overcome these last hurdles and move into the next phase. I think it is also important to not see the NCA as an end, but as a beginning of a new, perhaps more difficult, process.

Q: You also warned that the UN may reconsider its current support for ethnic groups if the ceasefire process is stalled beyond the election. Would the UN punish ethnic groups for not entering a ceasefire?

A: I am glad you have raised this point. I know that in Lawkheela a wrong perception was created as a result of a misinterpretation of my speech to the EAO Leader’s Summit. I would like to make this point abundantly clear. What I said was: ‘The UN will lend you all the support we can muster in this process. However, if such a process were to be delayed until after the elections, even we may not be able to say with certainty what the scenario from the UN angle will be. But nailing it down now could bring greater immediate commitment from the UN as well as the international community.’

The involvement of the United Nations in the peace process is based on the invitation by both sides. We cannot expect to enter the peace process without the explicit invitation by the parties involved. Every time the two sides have invited us, we have ensured that we were present. The UN remains committed to respond to any joint request and to deliver on them as long as they are within the Charter of the United Nations and the mandate of my office. While we have kept a low profile, we have been present at a large number of dialogues and summits. Our representatives have escorted armed groups’ representatives across the frontlines in Kachin before and after each peace dialogue. We have also been consistent in not pushing the parties or proffering help that was not asked for. But we have continued to stay strongly supportive and to respond to any agreed wish on the part of both sides. As for the future, no one knows what the political situation will be like a year from now. We have no clear indication of what the next line of leaders would wish from the UN in terms of its presence and involvement. Our initial presence was a concession from the UPWC to the KIO. The NCA does stipulate a continued engagement by the current observers to the process and if signed, we shall continue as such. If not, it will be for future negotiators to define the role of the UN in the process in consultation with us. We are not aware of many examples of high-level UN presence in Asian peace processes. After two years of our involvement, there may be some who may take the involvement of the UN for granted. But I shall only say this and say it unequivocally: The UN remains committed to the peace process and to supporting the people of Myanmar in their efforts at national reconciliation, regardless of the differences in their ethnicity, religion or gender. We trust the constructive elements from all sides in the country to come together, but I will also encourage you to set your own agenda and to be clear about how the international community can best help you.

Q: The Senior Delegation representing ethnic groups has said it will facilitate a meeting between President Thein Sein, army chief Min Aung Hlaing and Kokang group the Myanmar Nationalities Democratic Alliance Army (and the TNLA and AA). Will you be attending this meeting? What are the best case and worst case scenarios?

A: We have not been invited to these meetings and I shall not engage in any speculation about any possible scenarios. Many outside observers have provided their opinion on the peace process, judging it and drawing conclusions. I must say I am unable to make any quick judgment about something as complex and difficult as creating peace in Myanmar. I am aware of the time and effort invested by many leading figure in the peace process. These are people who have spent most of their lives in struggle. It is these people, and others who have suffered and continue to suffer but still persevere in their quest for peace. They have my utmost respect and admiration. I am also aware of the concern voiced through the media and social media from a wide variety of viewpoints. While some have been strongly dismissive of particular strategies they have not suggested alternatives. As I have already mentioned to you, the UN remains committed to the peace process and to supporting the people of Myanmar in their efforts at national reconciliation, regardless of the differences in their ethnicity, religion or gender. We trust the constructive elements from all sides in the country to come together, but I will also encourage you to set your own agenda and to be clear about how the international community can best help you.