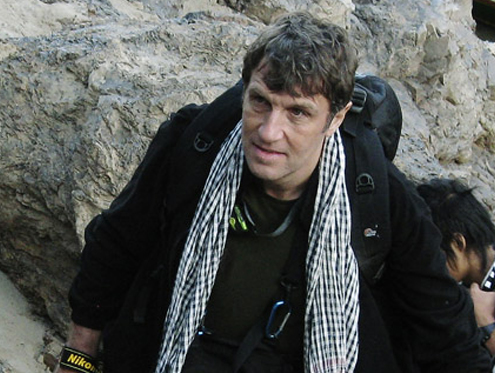

Thierry Falise, author of the newly released Burmese Shadows: Twenty-five Years Reporting on Life Behind the Bamboo Curtain, has spent a good portion of his professional career documenting Burma as photographer. Falise spoke with DVB’s David Stout about his new book and the challenges Burma is facing as the country continues to open up after decades of isolation and civil war.

First and foremost, congratulations on the new book. After spending 25 years documenting life in Burma, what do you hope your book shows readers during this time of optimism about the country?

My first hope is that this book will remain as a testimony of a rather long period (25 years, an entire generation) of the country’s recent and tragic history. As we all know, a country’s future can only be built upon its past. My ultimate wish is that most of the pictures in this book illustrating the more somber chapters of that history (oppression in ethnic territory and against the Bamar population, hard work, ethnic guerillas, child soldiers, production and distribution of narcotics, refugees and illegal migrants, etc) will one day become impossible to take.

What encourages you the most about this reform period and what do you think is being most overlooked at this time?

I went back two times to “Burma Proper” since August 2011 (just after Aung San Suu Kyi and president Thein Sein’s first meeting). In my eyes, the wall of fear has all but collapsed, it’s a sort of revolution in the people’s mind. The people I met (and whom I have sometimes known for years) in Yangon or Mandalay are not afraid any more to express their political opinion publicly (even though they all agreed to talk about these issues previously but in a very discrete way). I would even go further by claiming that this change of mindset is irreversible. If – in the worst scenario – the military (or part of it) decides to drag the country back into a dictatorship, I think the people would be ready to go down and die in the streets as they did in 1988.

For the second part of the question, I would say that as usual, the so-called “west” has a trend to shift from an extreme position (all black) to another (all white) with a sort of naivety or precipitation. I think the road towards a solid form of democracy (or at least of “liberalisation”) is still long. The path will be rocky. There will be backlashes. There is also the risk of an increase in the gap between the “two countries” – urban and rural Burma.

You’ve covered Burma for the past 25 years, what areas would you like to sharpen your focus on during the reform period?

I was always amongst these observers who believe that the complex issue of ethnic nationalities must be solved alongside other major issues. You must remember that the National League for Democracy in the late 1990s undertook its own “aggiornamento” by shifting from a bipartite to a tripartite dialogue. Political and economic stakes are too high in ethnic territories to be regarded as second priorities in the development of a new Burma.

With regards to how new investment will likely change Burma, what do you believe the government must prioritise with its preservation efforts?

As usual when a country opens its door to the outside world, it attracts all kinds of people, from the worst opportunist to the ethically minded entrepreneur (which is more rare!). We are observing this process now. There is a traffic jam of businessmen in Yangon, from the Eastern European crook to the worldwide American conglomerate’s CEO (which does not necessarily mean that the latter is ethically-oriented…). In an ideal world, Burma – as it restarts its economy from scratch – would be a perfect setting for the implementation of a new model that would allow for a more balanced economy. Unfortunately, we are not – and probably never will be – in an ideal world!

Now, one of the biggest issues that needs to be resolved for the country to move forward are the civil wars with several of the country’s ethnic minority groups. What can you say about the resolve of these groups that you’ve covered?

We cannot deny that a real and unprecedented effort has been undertaken by the government and under the lead of Minister Aung Min with the signing of ceasefires [with several armed groups]. Unfortunately, these positive steps are overshadowed by the dramatic situation in Kachin state (where a 17-year ceasefire between the government and the Kachin Independence Army broke down last year).

Still, although the situation in Karen state has largely improved (particularly after the signing of a ceasefire with the KNU) and for the first time in decades the civilians are experiencing a life without (or with much less) fear, the situation remains fragile. Much more concrete steps have to be taken by the Burmese army (troop withdrawal, resupply suspension, etc) before the KNU leadership and local population start to believe in a brighter future and in establishing a relation of trust.

Similar scepticism can be observed with other groups such as the New Mon State Party. The level of distrust toward the Burmese authorities remains very high amongst ethnic populations. As you know, there is a fear within ethnic ceasefire groups (and also with the Kachin Independence Organisation, hence the resuming of the conflict) that the government is trying to prioritise economic interests over a political settlement.

For me, ethnic groups’ main political goal – the establishment of a sort of federation – is very realistic. The world is full of federations, which are working. A new model focusing on ethnic lines must be sought after. It’s not going to be easy but it’s not impossible. The problem is that so far, in the Burmese military’s mindset, the word federation remains synonymous with separatism…

During your time covering Burma, you’ve documented the use of child soldiers. The Burmese government pledged this summer to end the practice. What will be the biggest problems to face with eliminating this scourge?

The use of child soldiers goes hand in hand with the absence of the rule of law. No modern army in the world – except in exceptional circumstances such as those engaged in wars – incorporate children into their ranks. So as soon as the rule of law is observed and reinforced in the country, the use of child soldiers will naturally vanish. Still today, part of the army – especially troops in remote ethnic areas – has not yet gotten rid of this bad habit and resorts to conscripting children.

A similar observation can be made within ethnic armies although the use of child soldiers by ethnic groups has rarely been as systematic (except with drug lord armies) as it is by the Burmese army. All in all I am rather optimistic about a positive and rather quick evolution concerning this issue.