DVB’s Editor-in-Chief on launching a shortwave radio station to provide Burmese citizens with independent information, in the aftermath of the devastating earthquake in March.

Originally published on Public Media Alliance

On 28 March, a 7.7 magnitude earthquake struck in Myanmar, close to the country’s second largest city, Mandalay. According to the military junta in May, there were more than 3,700 casualties, although many believe the real number is much higher.

Disaster risk reduction and crisis response are fundamental responsibilities of public service media, and there are countless examples of how public media strive to meet this challenge. Often, it involved close collaboration with the civil defence authorities and emergency services.

So how does this work in Myanmar, under the control of a military dictatorship, where many of the media companies are in exile, where citizens often face internet shutdowns, and much of the information provided by the authorities is treated with scepticism?

While this challenge affected all media companies trying to report on the earthquake, it was especially tricky for media companies who serve audiences inside Myanmar. Reaching these audiences has always been hard enough, but in the wake of the disaster, it proved even more essential that people in Myanmar could access independent and accurate information.

One organisation’s approach was to launch a shortwave frequency, where two half hour bulletins were broadcast to the entire country every day.

PMA’s editorial manager spoke to the Editor-in-Chief of the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), Aye Chan Naing, on why they took this approach, and how they covered the earthquake.

Harry Lock: How have the past few weeks and months been since the earthquake for DVB? What’s it been like getting information out of Myanmar? What have been the main challenges that you’ve been facing?

Aye Chan Naing: It was a devastating. We started around-the-clock coverage right after the earthquake. We moblized our CJ [community journalists] network in the earthquake-impacted areas and we managed to get a lot of stories.

Our main aim is to inform the authority and volunteers, hoping that they can save people who are being trapped. It was painful to watch [the] lack of assistance and negligence by the authorities as the days [went] to safe lives.

The main challenge is getting information from some of the areas because there is no phone line, no internet, and roadblock because the damaged cause by the earthquake.

HL: From a personal perspective, it must’ve been difficult, as I know a lot of the DVB staff will have family and friends still in the country – what toll has that had on DVB staff?

ACN: It is difficult as we all had families, relatives and friends in those areas. But luckily, no one was badly impacted.

HL: There’s been a lot of discussion about getting accurate information from Myanmar, with government officials tightly controlling the release of information to the rest of the world. What about for people inside of Myanmar – what sort of information are they receiving? And how accurate is it?

ACN: I believe most people [get] their news from exile media organisations like us. No one believes government news. For example, our Facebook page usually has about 30-32 million views before the earthquake. But on the day and the days after the earthquakes, it went over 100 million views.

HL: Prior to the earthquake, what have been the main methods of distributing DVB content to audiences in Myanmar?

ACN: We have satellite TV and varies online platforms. We have got 20 million followers on our Facebook page and three million subscribers on YouTube.

HL: Can you talk about the process of DVB launching a shortwave broadcast into central Myanmar? What steps did you go through before you made the decision?

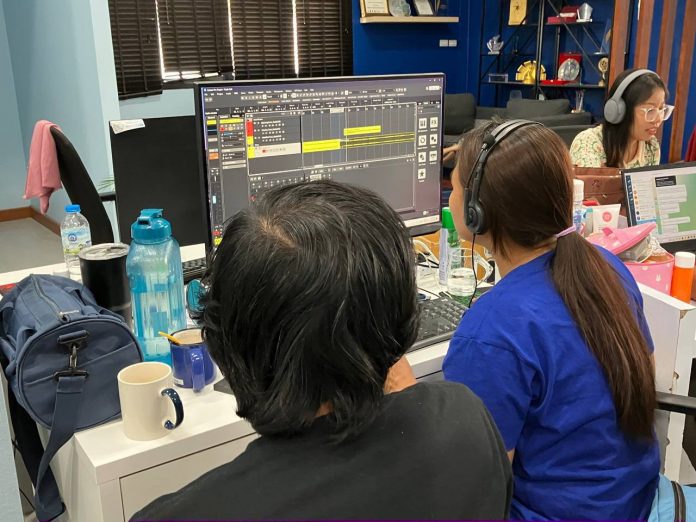

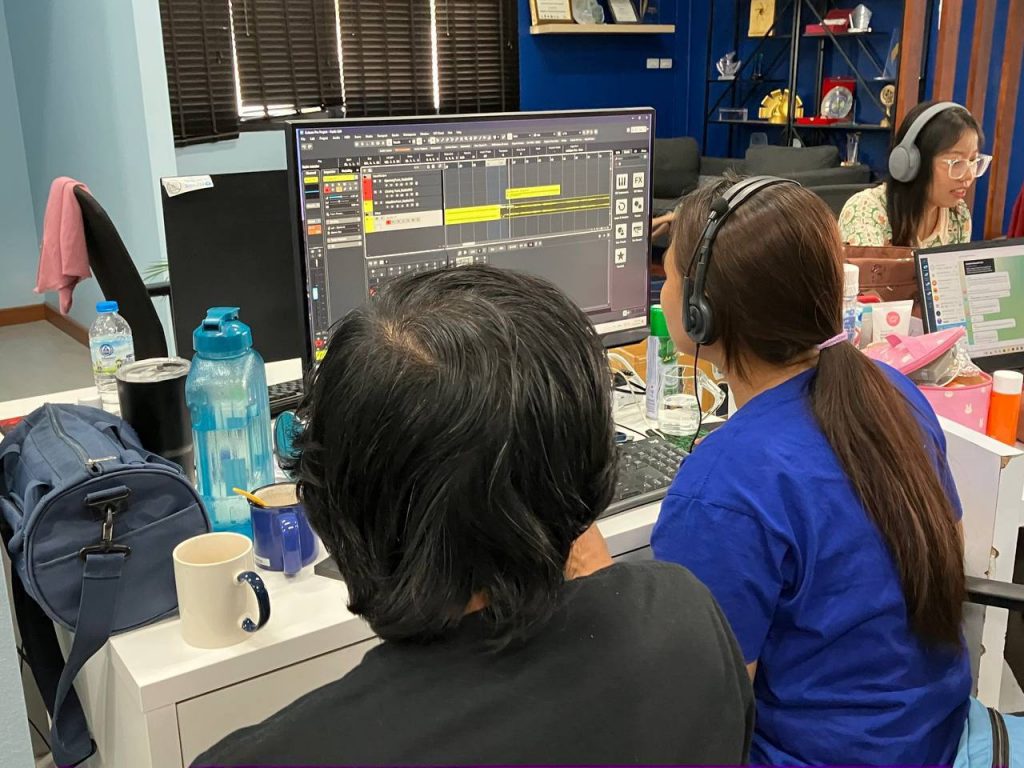

ACN: Since we had experience with last year cyclone emergency radio broadcast, this year’s broadcast was not difficult. And quite a few of our reporters have past experience in radio work. The same shortwave company provided the technical assistance for broadcasting and we have a team of 7-8 people working for the show and we aired half-an-hour morning and evening shows.

“Most people [get] their news from exile media organisations like us. … Our Facebook page usually has about 30-32 million views before the earthquake. But on the day and the days after the earthquakes, it went over 100 million views.”

Aye Chan Naing, DVB Chief Editor

HL: This time around, you’re attempting to distribute the shortwave signal across the entire country – in terms of infrastructure, cost, resourcing etc., how much more challenging is it to do this, rather than just one particular region/state?

ACN: It covered the whole country but unfortunately, we had to ended the broadcast mid May because we could raise the fund for transmission fees.

HL: Why shortwave?

ACN: Shortwave is the best way to reach people inside Burma. Many regions in Burma don’t have internet and electricity. Shortwave is the only medium that could reach [a] wider audience in the country.

HL: What sort of content are you broadcasting on this?

ACN: It is strictly limited to earthquake-related news and emergency assistance.

HL: Why does DVB decide to do this? What is your mission with this service?

ACN: Our mission is always public service. Inform, educate and entertain are our core mission.

The Public Media Alliance is the largest global association of public service media organisations.