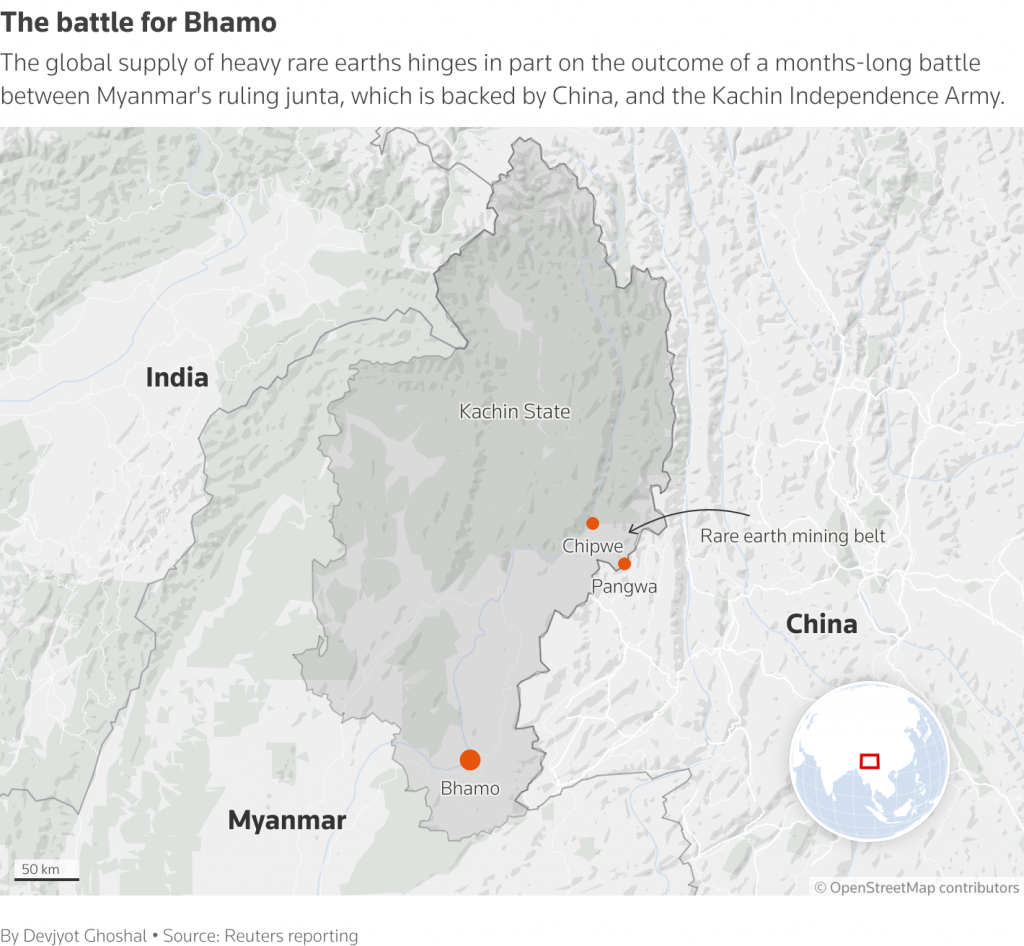

The global supply of heavy rare earths hinges in part on the outcome of a months-long battle between a resistance army and the Chinese-backed military regime in the hills of northern Myanmar.

The Kachin Independence Army since December has been battling the regime over the town of Bhamo, less than 62 miles (100 km) from the Myanmar-China border, as part of the conflict that erupted after the 2021 military coup.

Nearly half the world’s supply of heavy rare earths is extracted from mines in Kachin State, including those north of Bhamo, a strategically-vital garrison town. They are then shipped to China for processing into magnets that power electronic vehicles and wind turbines.

China, which has a near-monopoly over the processing of heavy rare earths, has threatened to halt buying the minerals mined in KIA-controlled territory unless it stops trying to seize full control of Bhamo, according to three people familiar with the matter.

The ultimatum issued by Chinese officials to the KIA in a meeting earlier this year, which is reported by Reuters for the first time, underscores how Beijing is wielding its control of the minerals to further its geopolitical aims.

One of the people, a KIA official, said the Chinese demand was made in May, without detailing where the discussions took place. Another person, a KIA commander, said Beijing was represented by foreign ministry officials at the talks.

Reuters could not determine whether China had carried out its threat. Fighting in the region has restricted mining operations and rare-earth exports from Myanmar have plunged this year.

China spooked global supply chains this spring when it restricted exports of the minerals in retaliation against U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs. It is now using its dominance to shore up Myanmar’s beleaguered regime, which China sees as a guarantor of its economic interests in its backyard.

China’s foreign ministry said in response to Reuters’ questions that it was not aware of the specifics of deliberations with the KIA.

“An early ceasefire and peace talks between the Myanmar military and the Kachin Independence Army are in the common interests of China and Myanmar as well as their people,” a ministry spokesperson said.

A senior KIA general did not respond to a request for comment.

The KIA official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters, said Beijing also offered a carrot: greater cross-border trade with KIA-controlled territories if it abandoned efforts to seize Bhamo, a logistics hub for the regime that’s home to some 166,000 people.

“And if we did not accept, they would block exports from Kachin State, including rare-earth minerals,” said the official, who did not elaborate on the consequences of an economic blockade.

Beijing is not seeking to resolve the nationwide conflict since the 2021 coup but it wants fighting to subside in order to advance its economic interests, said David Mathieson, an independent Myanmar analyst.

“China’s pressure is a more general approach to calming down the conflict.”

Defying China

The battle for Bhamo began soon after the KIA wrested control of the main rare-earths belt in Kachin State last October. After its takeover, the KIA raised taxes on miners and throttled production of dysprosium and terbium, sending prices of the latter skyrocketing.

Supply has been squeezed, with Beijing importing 12,944 metric tons of rare-earth oxides and metals from Myanmar in the first five months of 2025, according to Chinese customs data. That is down half from the same period last year, though exports rose more than 20 percent between April and May.

The KIA, which analysts estimate has over 15,000 personnel, was founded in 1961 to fight for the autonomy of Myanmar’s Kachin minority. Battle-hardened through decades of combat and funded by a combination of local taxation and natural resources, it is among the strongest of Myanmar’s resistance groups.

The KIA is confident of its ability to seize Bhamo and believes Beijing won’t ultimately carry out its threat to stop exports due to its thirst for the minerals, two of the people said.

Myanmar has been in crisis since the military overthrew a democratically-elected government in 2021, violently quashing protests and sparking a nationwide armed rebellion.

Swathes of territory were subsequently seized by anti-regime forces, but the KIA have come under Chinese pressure to make concessions to the military. Beijing has also sent jets and drones to the regime, which is increasingly reliant on airpower, according to the U.S.-based think tank, the Stimson Centre.

China, which has major investments in Myanmar, last year brokered a ceasefire for the regime to return to Lashio, a northeastern town housing a regional military command.

More than 200 km to the north, some 5,000 KIA and allied personnel have been involved in the offensive for Bhamo, according to a KIA commander with direct knowledge of the fighting.

Losing Bhamo would cut off the military’s land and river access to parts of Kachin and neighbouring region, isolating its troops housed at military bases there and weakening its control over northern trade routes, according to Maj. Naung Yoe, who defected from the military after the coup.

The regime spokesperson’s office told Reuters that China may have held talks with the KIA, but it did not respond to a question about whether it had asked Beijing to threaten a blockade.

“China may have been exerted pressure and offered incentives to the KIA,” it said in a statement.

Beijing first advised the rebels to pull back from Bhamo during negotiations in early December, according to the KIA official.

Instead of withdrawing from Bhamo after those talks, the KIA doubled down, according to the commander and the official.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies said in a May briefing that the battle for Bhamo had cost the KIA significant resources and hundreds of casualties.

Beijing became more confrontational during further discussions that took place in spring, when its representatives threatened to stop rare-earth purchases, the official said.

A disruption in the movement of heavy rare earths from Kachin could lead to a deficit in the global market by the end of the year, said Neha Mukherjee of U.K.-based consultancy Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

Supplies of the critical minerals outside China were already constrained, she said: “In the short term, during the brief disruption period, prices outside of China could shoot up higher.”

Battle for Bhamo

The KIA has pushed regime troops into a handful of isolated pockets, according to the commander.

But the regime retains air superiority and has devastated large parts of Bhamo with relentless airstrikes, according to the KIA official, the commander and a former resident of the town.

The regime spokesperson’s office said it was permitted to strike such sites because the KIA had been using them for military purposes, though it did not provide evidence.

Nathan Ruser, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute think-tank who has reviewed satellite imagery of Bhamo, said much of the damage across the town appeared to be from airstrikes.

Airstrikes have killed civilians, including children, and destroyed schools and places of worship, according to Khon Ja, a Kachin activist from Bhamo who said her home had been bombed.

“I don’t know for how long that the revolutionary groups will be able to resist Chinese pressure,” she said, adding that existing border restrictions had led to shortages of petrol and medicine in Kachin.

Despite the obstacles, KIA leaders believe capturing Bhamo would shift momentum in their favour and strengthen public support.

If the KIA were to take control of the entire state, then Beijing would have no option but to negotiate and sideline the regime, the commander and the official said.

“China, which needs rare earths, can only tolerate this for a limited time,” the commander said.

REUTERS