“Do you have an emergency basket at your door?”

This is a question that Ph.D. candidate Jenny Hedström soon learned to ask whenever she interviewed Kachin women about their support for and involvement with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) for her research on gender, peace and security issues in Burma.

“I spoke to a woman in an IDP camp who had lived through three episodes of very intense bombings in her village and was so fed up with it, but she had these clear patterns — almost obsessively making sure she had a basket ready for all her immediate family’s needs,” says Hedström.

“I then began to ask everyone who was a bit older, ‘Did you have a basket at the door?’ and they would all say, ‘of course’,” she recalls.

For women in Kachin State being prepared to flee a Burmese army attack at a moment’s notice is a skill every bit as important as growing rice, cooking food and caring for children.

An estimated 100,000 civilians have been displaced over the past five years of conflict in Kachin State — which is just one of many strife-torn parts the country.

One issue that often gets overshadowed in this and other conflicts is how they create conditions that make women more vulnerable to sexual violence and rape.

Renewed fighting in resource-rich Kachin State and elsewhere in Burma has often resulted in sexual crimes by members of the country’s armed forces.

“Rape is still being committed by those in the military. It’s about authority and it is very clear that they have impunity,” says Moon Nay Li, secretary of the Kachin Women’s Association Thailand (KWAT).

The way to eliminate sexual violence in conflict areas is by reforming the legal system and involving more women in the peace talks, say women’s rights groups. As Moon Nay Li notes, the system as it now stands is so deeply flawed that justice is all but impossible to achieve.

“We are trying to engage in a legal way but it is very difficult to find justice for any case committed by the Tatmadaw [Burmese armed forces],” she says. “Before the cases get to the Supreme Court, they disappear, they’re dismissed.”

KWAT is just one of several women’s groups working in Shan and Kachin states attempting to address the authorities’ silence by recording instances of rape and sexual violence targeting women in conflict situations.

One of the most brutal cases was last year’s alleged gang rape and murder of two Kachin volunteer teachers, Maran Lu Ra and Tangbau Hkawn Nan Tsin. More than a year later, no charges have been laid against those suspected of committing this brutal crime, prompting accusations of a cover-up.

This month, the Women’s League of Burma (WLB), an umbrella group of 13 ethnic women’s organisations, released a statement calling for a special independent inquiry into the murder of the teachers. Once again, however, the power of the armed forces in Burma’s political affairs continues to be an obstacle to justice.

“The same pattern remains: The military is not going under the government’s ruling even though we have a [political] transformation,” says WLB secretary Julia Marip. “We need to minimise the power of the military.”

The WLB has just submitted its shadow report on the UN Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) ahead of its scheduled meeting in Geneva in July.

The WLB’s recommendations highlight the prevalence of sexual violence in conflict areas and call for swift punishment of perpetrators. Additionally, they call for the permanent withdrawal of troops in ethnic areas; gender sensitivity training for public officials; involving men in efforts to eliminate violence against women; and for the government to allow community-based organisations to operate freely without restrictions or harassment.

“Conflict-related sexual violence is used as a tactic of war to demoralise ethnic communities, as punishment for supporting ethnic armed organisations,” states the report. “To achieve lasting peace the military must cease committing human rights abuses and women must have a significant roles at all levels of the peace process.”

To date, the Burmese military continues to turn a blind eye to the problem. It claims, however, to have provided “human rights education including all forms of violence against women” in defence academies.

Part of the problem is that despite Burma’s transition to democratically elected, civilian rule, the armed forces remain untouchable. Article 343 of the constitution grants the country’s generals complete jurisdiction over all matters related to national defense, including discipline for military personnel who commit conflict-related sexual violence.

Barriers to seeking justice

Another problem is that documenting rape is no easy task, as many of the ethnic villages are isolated and in conflict zones where women do not know their rights, says Khin Ohmar, coordinator of the organisation Burma Partnership, a network of regional and Burma civil society organizations.

“These areas are hard to get to, so what that tells us is the cases that many groups could document are still hugely under-recorded,” she says.

In 2014, WLB released a report detailing over 100 cases it has documented since 2010, including 47 gang rapes perpetrated by the Burmese military involving victims as young as 8 years old.

The culture of silence and the justice system’s failure to address such crimes is completely unacceptable, says Khin Ohmar. “The police and the court just throw the ball to each other and if the perpetrator is from the army, then the police say there is nothing they can do about it.”

She cites the court’s dismissal of the case of a 71-year-old woman who was raped in 2012 as an example of the weakness of a legal system that continues to fail victims of sexual crimes — something that has been evident again in the case of the two murdered teachers.

The social stigma surrounding rape also makes it difficult for victims to come forward.

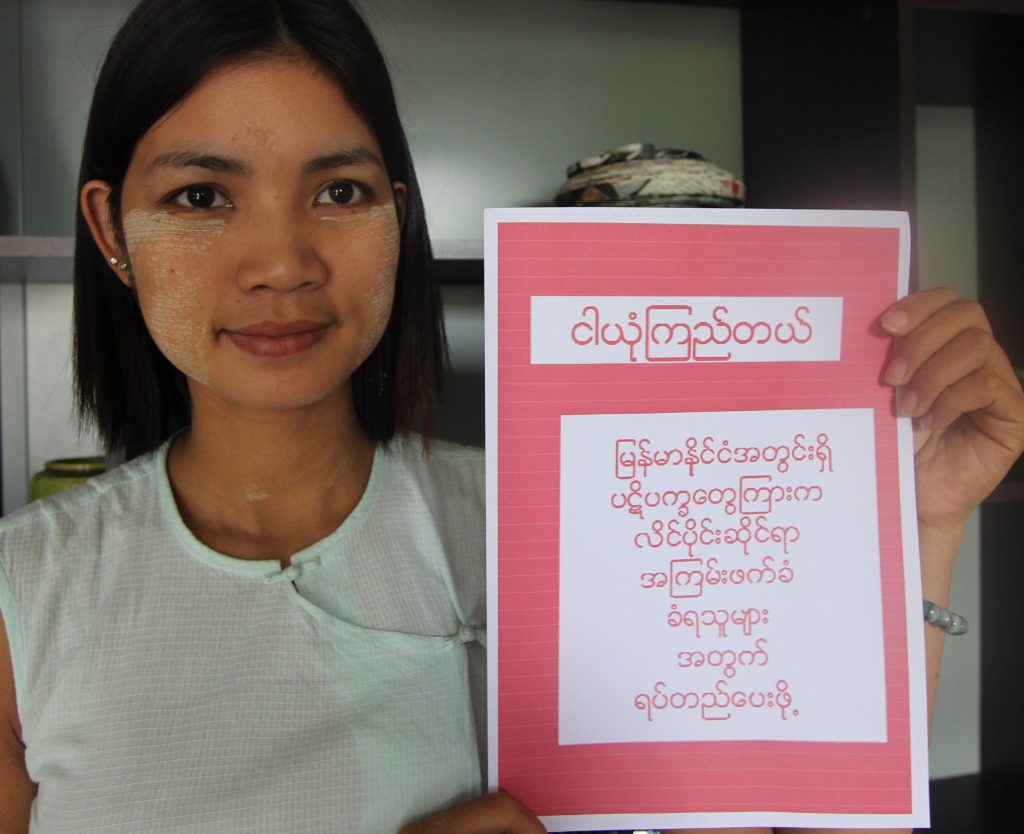

Akhaya Women, a Rangoon-based organisation that educates women about their body rights, recently launched their #webelieveyou #Isupportyou campaign to tackle the culture of victim blaming.

“Women need to know that we will believe them if they come forward to report these human rights abuses and that they are not alone,” says Maggi Quadrini, the group’s communications officer.

The campaign encourages women to share information through social media about support services for victims. The group has also launched a petition calling for an end to the silence of unreported crimes of sexual abuse.

Encouraging women to come forward and report rape is a challenge — not only because of the emotional trauma and fear of the military, but also because ethnic women are unable to access the formal justice system due to language barriers, costs and isolation from the nearest court.

Due to these barriers and other obstacles, including the government forbidding international non-governmental organisations from going to remote or sensitive areas in ethnic states for “security” reasons, many female victims try to resolve claims of violence through local village leaders.

KWAT is responding to these conditions by running one- to three-day workshops in ethnic communities with the aim of opening up the conversation on sexual violence.

“First we found that women didn’t want to talk about their experiences as it was like being raped again, sharing and retelling their story,” says Moon Nay Li. But they’ve found that open-group survivor empowerment programs are encouraging more women to come forward. They are also filling the void in government support services by building their own safe houses for victims of violence.

Empowering women

The only way to move forward towards peace is to start including women, says Hedström, the Ph. D. candidate: “I think it is pretty clear that the peace talks haven’t gone anywhere and so we need a new approach.”

According to Burma’s 2014 census, in Kachin State, it has the fourth highest reported rate of female headed households, yet they are still locked out of political talks.

Hedström says there is a common misconception that in ethnic areas, women lack the education and knowledge of the outside world they would need to play a more active part in moving the country towards peace.

“The women’s groups have the expertise that is needed to drive this peace process forward, because they are actively traveling internationally and they have experience in hearing conflict resolutions,” she says.

If the government is serious about making changes, quotas at all levels of government and in the peace talks needs to be mandated, say women’s rights advocates.

“At every level we are trying to promote women leadership and empowering survivors at the same time,” says Moon Nay Li.