After a chance encounter with a trishaw driver in Mandalay, Canadian Zen monk John D. Stevens formed a friendship that led to him forging a long-term connection with Burma, where he was inspired to build schools in poor, rural areas. This year his foundation, 100schools, will build its 50th school in November. John sat down to talk to DVB about how it all began.

Question: Tell me about what brought you to Burma?

Answer: In 1996 they opened the borders, so I’m a curious person and I wanted to know and see what it was that we weren’t allowed to see. In the beginning I was more of a tourist, but I really was taken with the place.

Q: Tell me about your first encounter with the people?

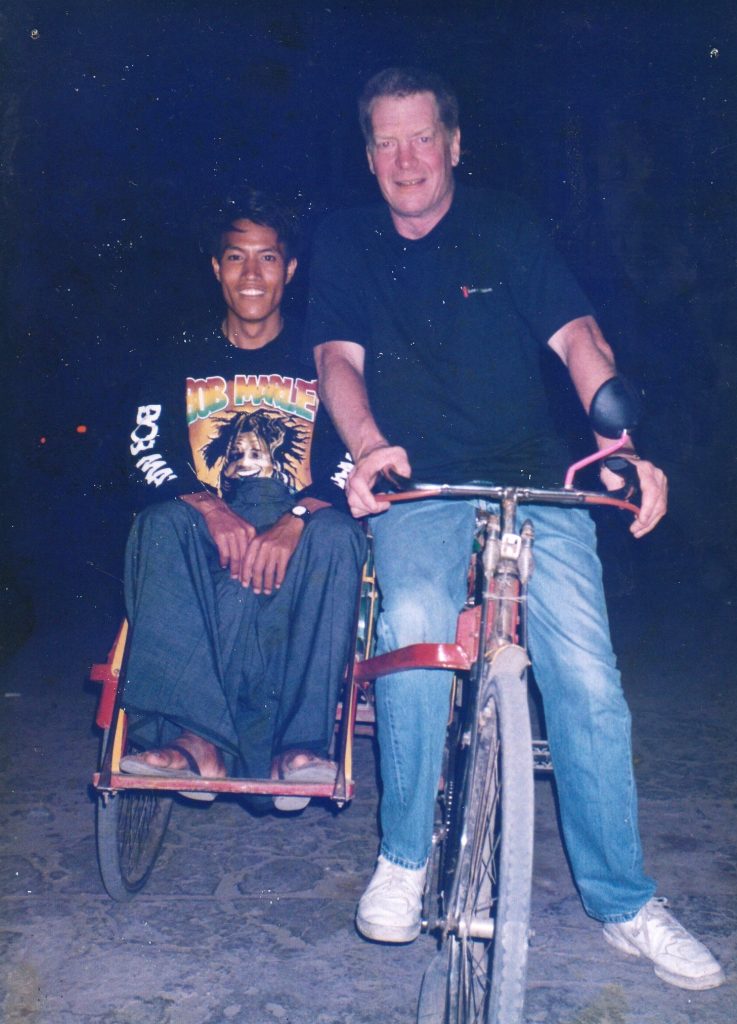

A: The very first person I ever met was this trishaw driver, Maung Maung Gyi, who takes me to dinner and refuses to take any money. I ended up being there for a week and at the end of that week I said you’ve got to let me pay you, but he just said, “No, no I just want to practice my English.” So I thought how do I pay this guy? I found this school where a teacher gives you some tapes and you sit in this room with everybody else and listen to your tapes. So that’s how I paid him, I enrolled him in this school and Maung Maung Gyi was so proud standing there with his tapes.

Q: When did you decide you wanted to go back to Burma?

A: So I left Burma but I had the bug. I went back to France where I was working as a chauffeur in a chateau near the Zen temple and any holidays I got I would go to Burma. So it ended up I was spending half the year in France, half the year in Burma.

Q: What was it about Burma that appealed to you?

A: It was the people. The villagers. They are the sweetest, most hospitable people. They are so kind and innocent. And what makes it so touching is for so long they were under this hammer since the early 1960s when the military took over. As Aung San Suu Kyi puts it so well, “Once the military took over, the lights went out one by one,” and so that’s the way it stayed for so long. And then I would like to say one by one they are turning back on.

The next time I came back, Maung Maung Gyi takes me to his village. When we pull into the town, Own Don, south of Mandalay, the kids come running out and they are kind of torn between looking at me and looking at the car. They hadn’t seen either of them. Then I met his father, U Pu (“Mr Short”), and we visited his onion fields. U Pu had this irrigation system which was a counterbalance of rocks on one side and paint buckets on the other so it took him all morning to bring up these paint buckets of water. I then bought him this generator and water pump, got it all assembled, fired it up and U Pu mumbles, “I’m retired” and laughs. For this $200 water pump he was not only able to irrigate his seven fields but in the late afternoons he would rent the pump out to other farmers. So U Pu goes from like the poorest guy in the village to the richest.

Then I thought we have got to do something here so it doesn’t create jealousy, so I said to Maung [Maung Gyi] we have to do something for the village, ask them what they need. They came back and said they needed a school.

Q: What were the schools like in Burma at that time?

A: They had this real lamentable situation for a school which every village in Burma did at that time because the government didn’t spend a penny. So all these village schools were over sixty years old and all falling down. We had enough money to put in wooden poles and a roof, but that was it. I took a photo of that school and when I went back to France and showed this picture to my boss, who had a lot of wealthy guests, and before you could say “education Burma kiddies” I had the money.

At first it was just one school a year then it got up to six or eight schools a year. Now we have a crew of 35 masonry workers and carpenters and we keep them working all year. We also build two schools at a time within one hour of each other, so when the concrete is drying on one school we then send the masons over to the other and switch with the carpenters. It takes three months to build two schools.

Q: How did you learn about building so quickly. Did you come from a building background or is it just common sense?

A: One word — Maung. He was working for a while in Thailand and he would work on construction sites and he learned this technique called confined masonry; horizontal bricks reinforced with iron bar frame and concrete. So if you have an earthquake the kiddies are going to be OK. The villagers also help us, which saves a lot of money and it means we can build a better school with nicer toilets, a better-quality roof, trees outside and shade, nice desks and a wall around the school. On some days we get up to 200 volunteers; some bring ox carts, some donate sand, or others might have rocks.

Q: How do you get donors?

A: I do speaking tours. For example, I was flown to Singapore recently to speak at a private school. Again, we also have some main donors: Myanmar/Burma Schools Project Foundation, Myanmar School Project, U R Building Knowledge and Pace Singapore.

If you look at the attendance records, in primary school you have 90 percent, but at middle school it drops drastically to around 60 percent, then lower again at high school. Why? Because the family needs the kids to work with them in the fields. So when we build a school, Maung Maung Gyi talks to the villagers about the reason why we are building new schools — it’s not just a nice new building. So he presses on them the value of education and we make them take an oath [to send their children to school]. Then at the end of my opening speech I thank the villagers, and instead of them sitting back and watching, they can say, “We built this.”

Q: Why did you also start to make uniforms?

A: We brought in the uniforms because I thought it was really unfair that uniforms are mandatory for two days a week but some kids couldn’t afford them. The quality of the uniforms also rubbed me the wrong way — it’s cheesy, papery in the collar — so we started our own uniform factory of five ladies and they sew 25 a day.

Q: What about the students, are you also providing scholarships?

A: We hand out scholarships to those who are really bright from poor families. At the moment we have two kids at college; one who is studying IT for three days a week and then three days he is studying English and then this guy is going to work for us. The other student has also just started college, studying to become a teacher. So soon we are going to start computer labs in schools.

Q: So what’s the future? Are you going to reach 100 schools?

A: When we actually get to the 100th school I will probably be in a better position. Who knows, I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it. I might keep on doing the same thing or I might go to another country, or I wouldn’t mind building 100 RHCs (Rural Health Centres). As for schools — over 7,000 schools are wrecks in the country, and over 2,000 schools are actually dangerous. So you know, I am not going to run out of schools to build — but I want to spread them around. I would like to build at least one school in every division.