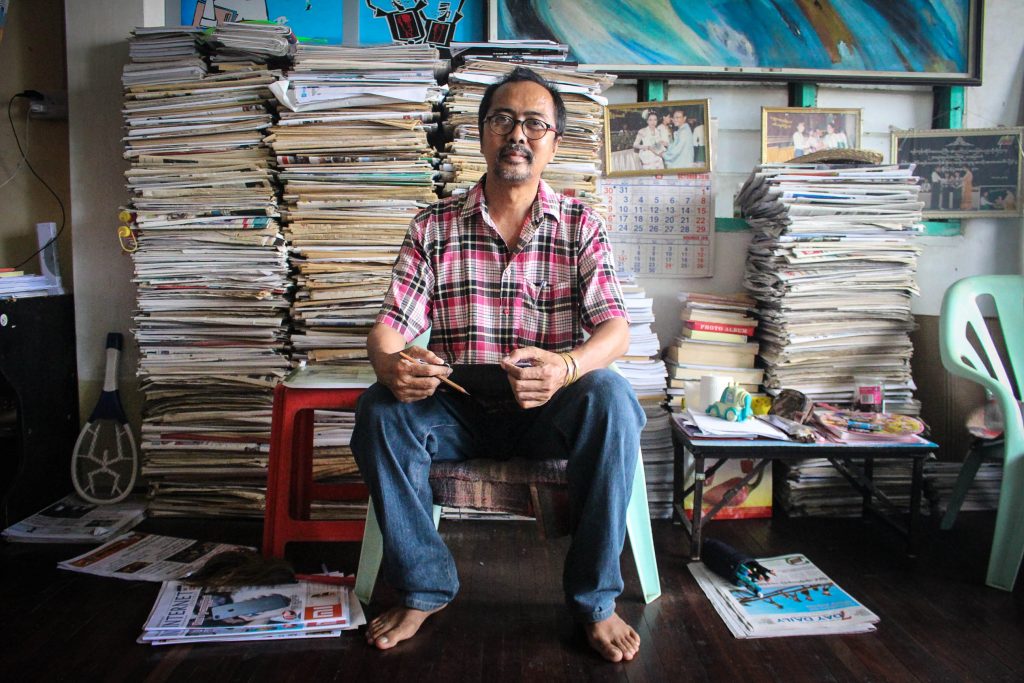

“Have you been to the national library?” asks San Mon Aung. The author and local publisher at WE publishing house and NDSP Books sits opposite me, on the edge of his stool, leaning his elbows on the table supporting his animated hands as he talks. It’s only 10 minutes into the interview and already the tables have turned and he’s the one asking questions.

He continues, “or better still, you should ask youth today on the streets, not even if they have been but where is the national library?”

San Mon Aung has made it his mission to reconnect Burma’s younger generation with books. He plans to open the first book plaza in Rangoon next year. It will include book shops, offices, cafes and a memorial space for famous authors. He hopes the space will be more than just a commercial building, but rather somewhere “the younger generation can hang out”— share ideas, hold poetry events and experiment with ideas.

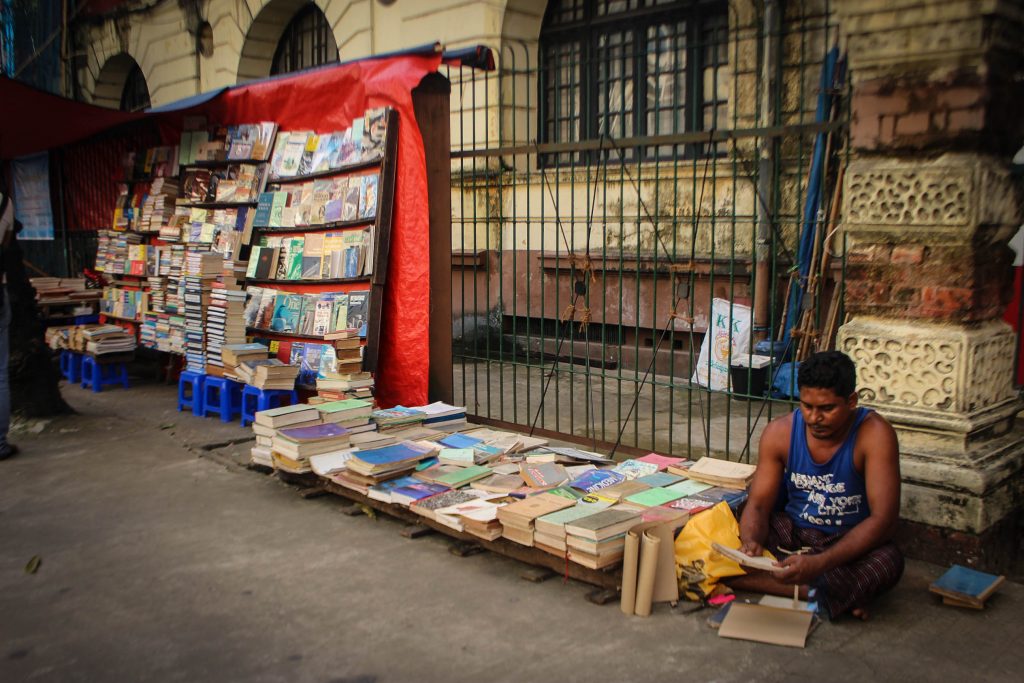

While other countries have experienced the closing down of bookstore chains like Borders, the publishing industry is yet to take off in Burma. Rangoon might be famous for its open-air second-hand book stands, but new books are still a rare luxury.

Previously writing under censorship, San Mon Aung used the pen name “Myay Hmone Lwin”. He says the former military government “thought writers were a public enemy.” Writers, journalists, and many members of the art community were subject to censorship, intimidation, unwarranted searches, arrest or long spells in jail.

He said it was difficult to know what the censorship board would ban and what they’d allow, as there were no clear rules. He recalls how he was asked to make changes to his work for random reasons. On one occasion, he was asked to change the front cover of a collection of short stories because the authorities said an illustration of a character with a bald head resembled Zarganar, the well-known comedian who was a political prisoner at that time. “There were many ridiculous things,” shrugs San Mon Aung. “I was really surprised and asked why. To be bald is not criticising the government. So I couldn’t understand what they meant.”

On another occasion, he was banned from using the number 54 as it was thought to be a metaphor for Aung San Suu Kyi, whose house is at 54 University Avenue in Rangoon’s Bahan Township.

Since the press scrutiny board was dissolved in 2012, artists and writers have thrived in the new freedom to express their views both critically and creatively.

But when asked if there is total freedom of expression in society today, San Mon Aung hesitates. While he certainly believes the situation is much better than it was in the past, he warns, “we do have to be very careful about religion and the military.” Other topics like erotic fiction are also still taboo.

The powerful weapon of the pen

Political cartoons have historically been one of the areas in which the artists of Burma could poke fun at the government or the military elite but dance around the laws of defamation or censorship. After the 1962 military coup, the authorities instituted censorship and clamped down on political expression. Cartoonists were tested in their ability to draw cartoons that planted subtle messages that were abstract enough to escape the wrath of the authorities, yet still communicated their intended satire and entertained audiences.

Soe Thaw Dar was inspired to pick up the pen when he came across cartoons of the revolutionary era after colonialisation, such as those by political cartoonists Shaw Talay and U Ba Gyan.

“The political cartoon culture was born at the same time as the political condition in 1915,” states Soe Thaw Dar.

He divides cartoonists into three categories: those who draw for children, those who deal with social issues, and political cartoonists. His own interest, he says, has always been in political cartoons. “Particularly from 1988 to 2012, during the previous era, the people were oppressed and discontented so I had this feeling that I wanted to express what the people felt.”

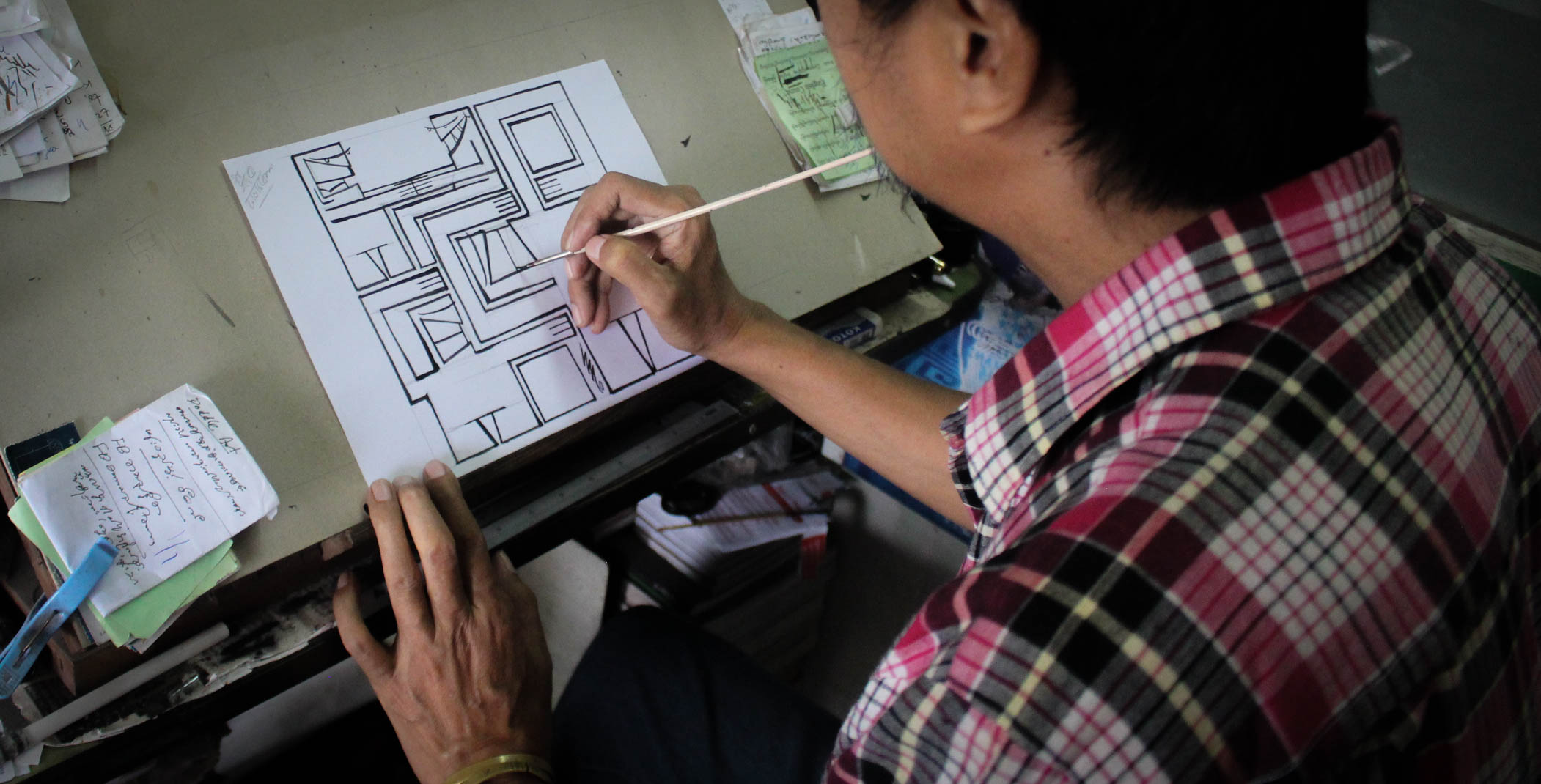

Rather than seeing technology as a threat, Soe Thaw Dar eagerly embraced the computer and particularly programs like Photoshop. “Technology has helped me a lot — before I couldn’t use the computer so I had to copy and paste my images to make an artwork.” Now his process involves freehand sketching. He then scans his image into the computer and experiments with different colours and textures and creates cartoons that have a certain pop-art or collage quality to them.

One of his recent cartoons for 7 Day News illustrated the case of the tourist who unplugged a speaker during the broadcast of a Buddhist recitation in Mandalay. His cartoon, “The silent protest”, touches on the taboo subject of religion, which is so sensitive that it is difficult to even discuss the use of loudspeakers for religious events.

Education and art

Singing reggae music is not a profession but a life choice for singer Saw Phoe Kwar. Not content with just spreading the message of peace by recording songs and making an album, he has recently started a new mission of visiting schools and communities in areas of intense conflict. Last week he visited northern Shan State and performed several small concerts where he interacted with the young local audience.

“I want to target children from the ages of seven to 20 years old [with] only one message,” he says, pausing for a moment to clear his throat before continuing: “Peace and one love for our future.” He encourages children to ask questions at his performances and invites former political prisoners onto the stage to talk about their experience. “The children can learn for example, ‘Hey, this guy was a prisoner for 20 years but he doesn’t have feelings of revenge, he loves only peace’.”

Described as Burma’s Bob Marley, he performed mostly underground or in small festivals during the era of censorship. When it came to recording songs, he experienced the same challenges as artists in other fields. On his first album the censorship board objected to three of his songs, including one that used the phrase, “Let’s do the right thing, let’s say the truth.” They didn’t explain what was wrong with this — they just put a firm red line through the words.

Despite the new freedom for songwriters, he says there is still a major barrier in people’s minds. Young artists still believe covering popular songs is the key to becoming a famous singer. Saw Phoe Kwar disagrees with the copycat culture that he says prevails in Burma’s entertainment industry: “If you take my song, [you] are a thief, the same as if I did like that. Everyone has a different gift. They just need to use it.”

San Mon Aung also believes that targeting the younger generation at a school age is important for instilling the seed of creativity and encouraging children to explore. He believes that updating the school curriculum so that there are new and engaging texts is important “to change the education system totally and also our reading society.”

In time he hopes more writers will push boundaries: “There are still a lot of challenges and our society is very closed off and narrow-minded so a lot of people don’t accept experimental things.”

What all artists have in common is their emphasis on the individual, the artist, as an agent of change. “People think that when the government changes, their life suddenly changes — it’s not true,” says San Mon Aung. “If you want to change, you must change yourself. You must change your society, your family, first.”

Saw Phoe Kwar puts it simply: “Love one another.”

By the way, the national library is on Thiri Mingalar Yeikthar Road in Yankin Township.