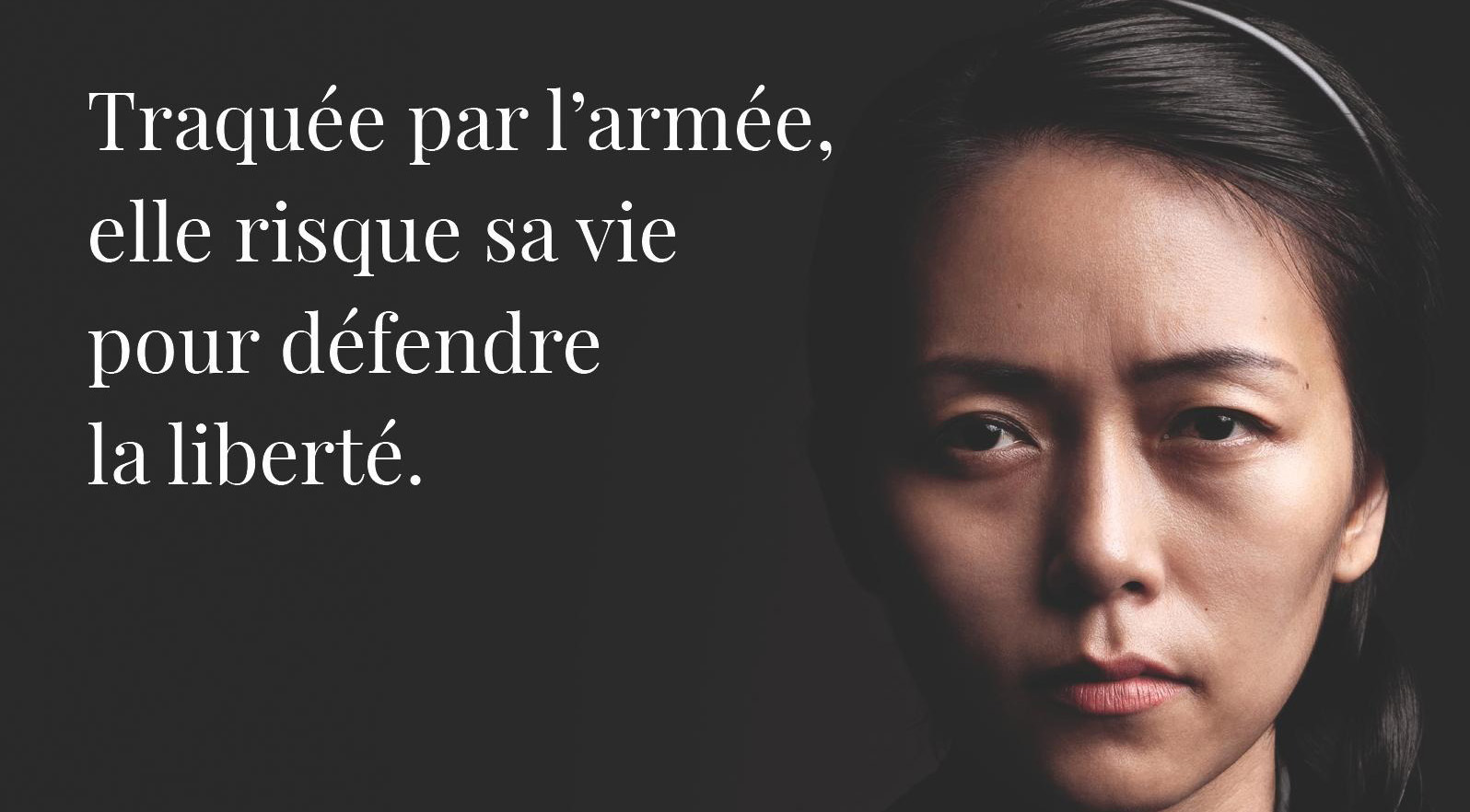

Yesterday saw the publication, in France, of Mon combat contre la junte birmaine, a memoir which will likely prove to be the first of many vital foreign language accounts flowing from the Spring Revolution.

DVB sat down with pro-democracy activist, Thinzar Shunlei Yi, and her Paris-based co-author, journalist Guillaume Pajot, to discuss their personal experiences of activism, the coup, and living and writing in Burma under the spectre of the military.

Give us an oversight of the plot of the new book. When does it start, and what can we expect it to include?

Shunlei —The book covers the history of Myanmar’s revolution in both the past and the present through the story of a young woman who successfully transformed herself from pro-military to pro-Aung San Suu Kyi, and from pro-Aung San Suu Kyi to a human rights defender and democracy activist.

Freedom of expression is under the worst possible attack in Myanmar. This book is one of many ways that we are combating the attack on our free speech; it is a defense of the right to publish.

How has your attitude towards activism changed since February, if at all? How has the coup changed your day-to-day work?

Shunlei —The February coup did not change any concept that I had developed over the past five years; it just proved that the “reforms are fake” argument was correct. This attempted coup made us busier: first in organizing, mobilizing, and resisting, and then in turning our efforts into a full-blown revolution to root out the military ideology that has been deeply embedded in society for decades.

We are not merely a handful of activists anymore. We have been joined by many innovative activists all of whom have different resources and capacities.

You are telling your story for a global audience, perhaps for some who do not know what is happening in Myanmar. How do you balance telling an authentic and detailed narrative while also keeping it accessible to readers from around the world?

Shunlei —I have been an advocacy coordinator for a grassroots political coalition for more than six years now. I still work with grassroots leaders, and I advocate their demands to politicians and the international community. These previous experiences have developed my understanding of what to say, how to say it, and whom to say it to across different situations whilst remaining principled.

It also requires me to keep myself balanced whilst also being aware of what is going on on the global stage. It has taken me many years to hone this skill and understand this balance, and I’m still learning from my seniors. Essentially, this book is another attempt at the kind of advocacy that I was performing in the past; I did TV shows, forums, conferences, panels, statements, protests, performances, festivals, radio podcasts, articles, reports, using many different stages to reach a wider audience. This book is another tool for advocacy in which I discuss my roots and other detailed personal information.

I have never before let anyone know the details of my personal life, or of the thoughts that I have developed whilst undertaking this journey in activism. This is my first attempt at trying to explain why I’m doing what I do, and also at outlining what I believe readers should be doing for Myanmar.

Name some obstacles that prevent citizens of Myanmar from telling their stories.

Shunlei —People are telling their stories in their own ways: by writing on social media, like everyone else, and by acting against the junta. We need to listen closely to each of them who choose to speak up. Where people are stopped from speaking out, we need to use our freedoms and privileges to be a voice of the oppressed. We must respect and amplify the Myanmar peoples’ on-going struggles and voices from the ground.

Should publishers decrease their reliance on the Western academic narrative when talking of Myanmar? If so, why?

Myanmar hosts the world’s longest running civil war: seven decades. No world leaders have ever put an end to this fire. The recent ten-year transition period and the peace process was also a failure. We say that this window provided many opportunities, but we must admit that we failed to address the deep-rooted problems of justice and accountability with the military-drafted 2008 constitution. It was as if we walked out of this window newly created, but naked and not knowing where we were heading. Myanmar’s solutions are in the hands of its own people. Minority communities have been fighting against the same institution for so long: they know their enemy the best, they have the answers. We need to listen to them harder, to ask questions. Myanmar people need charity, but we need solidarity the most.

What do you feel needs to be done to amplify Myanmar voices in publishing globally?

Shunlei —International media should remind people who believe that they live in a parallel universe on the same globe that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”. Myanmar’s continued struggles and conflicts constantly highlight the need for change within the UN system, and the world’s wider mechanisms for justice. The impunity that the junta’s leaders have been enjoying are beyond limitation; the brutalities that Myanmar people face are a direct threat to humanity as this impunity inspires aspiring dictators around the world.

As someone from a military family, what do you think are the constraints on those in a similar position who wish to speak up? Would you say that most children of officers feel conflicted by the current situation?

Shunlei —I noticed long ago that children of the military are caught in the middle, confused about where to stand on difficult issues. They need the exposure to life and the knowledge that I once needed. I used to organize low-risk political activities, inviting my classmates—juniors and seniors from the military high school I attended—to participate. They were close to me and my growing activism. In the wake of the coup, I saw that those who had got involved with the activities that I led were clear who to support.

I would say that, in general, the younger generations of those from military families have a clear consciousness of what is happening around them, and more of an ability to stand for what is right. However, the ability to speak up publicly involves another level of risks that they must take—I’m publishing my story now to encourage them that not supporting the junta isn’t enough. We need to be proactive against the junta; I’m currently co-organizing panels that invite defected soldiers and military family members to speak up their truths, to advocate for further defections from the military.

What do you see yourself focusing on in the next six months?

Shunlei —When I look back at the past six months, I see myself pushing boundaries that I never thought I could. Also, I saw myself implementing ideas that I had developed over the previous six years. It’s the revolution and the spirit of the Myanmar people that allows a young woman like me to continue to be the best version of my fighting self during the revolution. The next six months seems very far to me now and, with a heavy sigh, I would say I wish that, in that time, I could go back home and see my family.

Guillaume, what brought you to Myanmar, and what is your own personal experience of the coup? What has been most personally affecting, most impressive?

Guillaume —I went to Myanmar for the first time in January 2011. Back then, I was a young journalist, and it was another junta. Two months later, in March 2011, the military announced the power would be transferred to a “civilian government”. It shocked me, I came back, followed the story and never stopped reporting from Myanmar, even though I’m based in Paris.

On February 1st, 2021, I woke up and turned on my phone. Suddenly, I was flooded by messages from friends and sources in Myanmar, telling me about the coup, because in France we’re not in the same time zone. I was deeply worried, many of them are journalists or activists, so I checked on everyone’s safety. I started a Twitter thread to document the coup, day by day. I felt powerless, but kept on writing articles and stories, on the military, on Insein prison or else, even though I couldn’t enter Myanmar.

The coup isn’t just another coup, it’s been a life-changing moment for many Burmese. I saw friends protesting, then fleeing the country, hiding in the jungle or taking arms. Some of them have been arrested. Some others tortured. Their stories need to be heard.

Would you say that your work on Burma is now more important than before?

Guillaume —I have been working on Myanmar for almost a decade and to me, it has always been important to follow the country closely: the so-called “democratic transition”, the Rohingya crisis… There were so many important stories to tell.

Today, the important work is done by local journalists and photographers. They are doing an amazing job at great risks. Myanmar Now, Frontier, DVB, Khit Thit Media… I read what they publish everyday. They are the ones doing the important work.

Has the book been edited to appeal at French audiences in particular? If so, why?

Guillaume —We wrote the book for a wide audience, but not specifically French. It’s a full narrative, there are twists and turns. Anyone can relate to the story, we explore themes like family issues, growing up in Myanmar, feminism, fighting an authoritarian regime, friendship… And of course we explore the last decade in Myanmar, the coup and its aftermath, and we dive deep into Thinzar Shunlei Yi’s childhood in the military barracks – it tells you a lot about the military mindset. I write in French, but the book is for everyone. I hope there’ll be translations in English or Burmese at some point.

Mon combat contre la junte birmaine, published by Robert Laffont, can be purchased here.

Thinzar Shunlei Yi is a Burmese democracy activist defending Human Rights for over a decade. Amongst the first to oppose the military regime, she has been singled out by the Obama foundation and is a laureate of the Women of the Future Southeast Asia Award in 2019. She is followed on social media by a large community of Burmese as well as by people from all around the world – more than 40,000 followers on Facebook and Twitter.

Guillaume Pajot is a French journalist and a specialist on Myanmar. He has worked for prestigious French and international newspapers and magazines such as Libération, XXI, L’OBS or GEO… His documentaries have made the shortlist of the Albert Londres Prize, the highest French journalism award, as well as of the Bayeux Calvados-Normandie Award of War Correspondents.