The Union Parliament (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) engineered a constitutional crisis in September last year when they impeached six tribunal judges for issuing a ruling they did not agree with. Since then the crisis has only worsened.

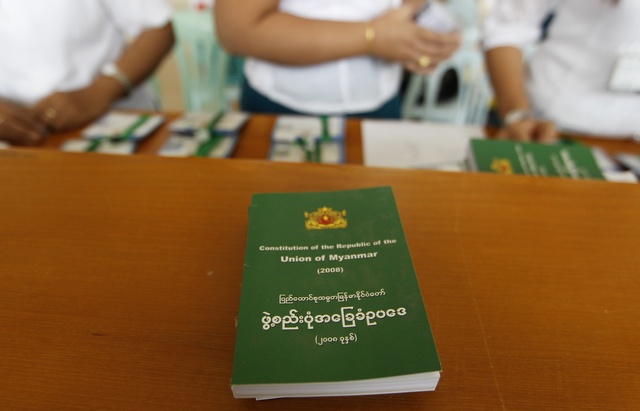

They are currently pushing through amendments on the existing constitutional tribunal law, even though the president has described them as “unconstitutional”. Indeed, President Thein Sein has highlighted three major points, which violate the 2008 constitution.

Article 321 of the constitution states that it is up to the president to submit the name of a candidate to be assigned as the chairperson of the constitutional tribunal to the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw for its approval. But the Hluttaw’s amendment contrarily mentions that, in selecting the candidate, the president shall consult with the speakers of the lower and upper houses of parliament.

Secondly, the legislator’s amendments require all members of the constitutional tribunal to submit regular reports to the president and both speakers of the two chambers.

President Thein Sein argued that such provisions infringes on the rights of the constitutional tribunal, as the highest court of the country, to adjudicate constitutional issues independently. The act also contravenes the judicial principle, that is, to administer justice independently, in accordance with Article 19 (A) of the constitution.

The president also noted that the amendment restricts the power of the tribunal, by prescribing that the resolution of the constitutional tribunal shall be final and conclusive only with disputes submitted by a court. This measure implies that, for other constitutional disputes, a party, who is not satisfied with the resolution of the tribunal, can appeal or revise the decision, which is also contrary to the constitution.

If the provisions in the amendment are contrasted with the relevant articles in the constitution, even laymen can vividly understand that the Hluttaw has violated the constitution, which was adopted as the supreme law of the land.

Despite the fact that the president raised these constitutional issues, he did not stand against the resolution of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw. He was well aware that even though he refused to sign the bill, after the completion of a 14-day period the legislation would become a law as if he had signed it in accordance with Article 106 (C) of the constitution.

[pullquote] “Authentic political power in Burma primarily lies with the legislator, not with the president” [/pullquote]

More importantly, if he refused to sign the amendment, tension between the Hluttaw and himself might reach a tipping point and result in Thein Sein’s impeachment by the parliament, a fate that was meted out to the justices of the constitutional tribunal when they dared to cross the legislators. As a result, the Hluttaw has strengthened their hand.

Authentic political power in Burma primarily lies with the legislator, not with the president. U Khin Aung Myint, the speaker of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw has proclaimed its power by repeatedly stating in the past that, “above the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, there is only the sky.”

The recent episode clearly demonstrates that the president is subservient to the parliament. However, it’s important to remember that the authorities have created a “win-win situation” for both the president and the Hluttaw.

So why then did president Thein Sein publicly address the constitutional dispute? He elaborated, while also noting his awareness of the constitutional violations enacted by the Hluttaw, that he was signing the legislation to show his respect to the will of the parliamentary majority.

There may be several background scenarios at play here.

Thein Sein may be concerned about his standing within the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), which holds a majority of the seats within both legislative bodies. Although he still heads the USDP, the Hluttaw’s rejection of his comments reveals that he may be losing support within his own party.

The president may also be trying to make an impression with the Burmese public and the international community by portraying himself as a democratic leader, who values transparency as far as the lawmaking process is concerned. He also likely hopes to portray himself as a president who appreciates democratic values, promotes the independence of the judiciary and preserves the rule of law.

Superficially speaking, this may be the case. Thein Sein may achieve his political objective should the Burmese people and the international community fail to analyse the situation manifestly.

Understanding the parliament

The majority of members within the incumbent Hluttaw do not value democratic principles, given that they were not chosen by the people in free and fair elections. During the general elections in 2010, the USDP won a majority of seats in the legislature by employing fraudulent practices. The Union Election Commission even admitted as much.

In addition, without being elected, the representatives from the military, who were hand selected by the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, constitute one fourth of the total number of both chambers. As such, Thein Sein’s statement that he paid respect to the will of majority of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw is groundless and does not reflect his embrace of genuine democratic values.

Even if the Hluttaw were a genuinely elected legislative body, they shouldn’t be allowed to adjudicate legal and constitutional issues by simple democratic means, i.e. after listening to arguments from four people, two of which are military representatives.

While Thein Sein addressed the independence of the judiciary, he failed to mention two key points – the appointment procedure of judges and judicial tenure. The 2008 constitution lacks the necessary provisions in this regard. Legal academics from the International Bar Association recommended forming a judicial appointment board to support the emergence of an independent judiciary in December 2012. Neither government authorities nor MPs paid any attention to these recommendations. Contrary to the 2008 constitution, judicial tenure was outright guaranteed in the 1947 Constitution of Burma.

In a nutshell, the constitutional crisis faced by both the Union Parliament and the president emanated from their ploy to subordinate the judiciary.

President Thein Sein said that he would submit this dispute to the constitutional tribunal, which would be reactivated with the newly appointed members. What would happen if the tribunal rejects their amendments?

If the Hluttaw complies with its resolution, as the final and conclusive one provided for in article 324 of the constitution, the impact would be far-reaching. The amended law, already signed and promulgated by the president, would be abrogated.

Most importantly, the resolution of the new constitutional tribunal would also affect the status of the former one. When the former tribunal made a resolution, which denied parliamentary committees union-level recognition, the Hluttaw refused to abide by that. Because the parliament was unhappy with that resolution, all nine members of the former tribunal were impeached and forced to resign.

Should the Hluttaw comply with the resolution of the new tribunal, it would mean that it practices selectivity. In that case, the rule of law effectively goes out the window. And if the legislator does adopt the resolution of the new tribunal as a final and conclusive one, legal questions would undoubtedly arise.

Was the Hluttaw’s denial of the resolution passed by the former tribunal illegal? In that case, what would be the legal remedy? Do the members of the former tribunal, who were forced to resign, have any legal right to claim for their grievances? Would previous resolutions made by the former tribunal still be effective, as final and conclusive rulings?

If the Hluttaw should refuse to comply with an unfavourable decision made by the new tribunal, the constitutional crisis would escalate. What would the former do? Would it impeach all members of the new constitutional tribunal repeatedly? Would it amend the constitution? Burma has no way to overcome this constitutional crisis if the authorities observe the genuine principles of the rule of law. Thus, this may also be beginning of the end for the 2008 constitution.

Aung Htoo is a human rights lawyer. Email him at: [email protected]

-The opinions and views expressed in this piece are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect DVB’s editorial policy