The Committee for Scrutinizing Remaining Political Prisoners (CSRPP) will continue work through 2014 – despite government claims that all political prisoners were released by 31 December – according to committee member Bo Kyi, who is also the founder and joint-secretary of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners in Burma (AAPP-B).

He told DVB on Tuesday that “we need to continue because there are still political prisoners in Burma.”

President’s Office Minister and Committee Chairman Soe Thane, in keeping with official statements that all prisoners of conscience had been freed by the end of 2013, said that the CSRPP will continue so that, “if something happens, the committee will be ready,” according to Bo Kyi, who added that the government has not conceded that any other activists are still in detention.

The AAPP-B, which has maintained a roster of current political prisoners since 2000, says that upwards of 33 prisoners of conscience are still behind bars, despite the government’s insistence that they have all been freed.

The CSRPP was established in early 2013, just prior to President Thein Sein’s June 2013 promise to free all dissidents by the end of the year.

Complete amnesty for political prisoners was a common condition among Western governments for lifting decades-long sanctions imposed on the former military-ruled country.

While a series of presidential pardons have been welcomed by the international community and Burmese activists alike – nearly 1,200 political prisoners have been released since May 2011, 57 in December alone – political and human rights groups have shown reluctance to reward the government.

“I am very pleased for the families of political prisoners who have been released, but we must remind ourselves that they should not be in the prison in the first place,” read a 3 December press statement by the Kachin National Organisation (KNO).

[related]

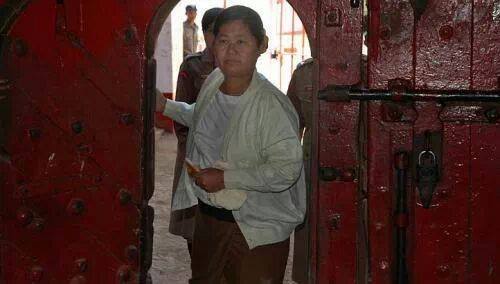

The group said that while many were pardoned for crimes they should not have been jailed for, others are still being held on charges they consider dubious, such as Kachin land rights activist Bawk Ja, who is currently in custody awaiting trial for “negligent homicide” after a patient in an unauthorised clinic died, allegedly under her care. The KNO called this a “politically motivated case to handicap her political career”.

Similarly, Naw Ohn Hla, well known across Burma for her role in the anti-Latpadaung mine protests, was recently charged for “religious offences” she purportedly committed in 2007. The charges were brought against her within one month of a November amnesty, during which she was pardoned for sedition charges associated with the anti-mine demonstrations.

The trend towards re-imprisonment has been dubbed “the revolving door” of Burma’s prisons. DVB reported last month that at least two of those freed in an 11 December amnesty were put back in jail the very same day on separate but related charges.

It has also been suggested that the pardons have been used as “political bargaining chips”; the 11 December amnesty, which – temporarily, at least – freed 41 people, was announced on the same day as the opening ceremony for the SEA Games, an international sporting event that drew nearly one million visitors to Burma including foreign heads of state, and threw the country momentarily into the international spotlight.

Soe Thane has reportedly requested and cancelled two CSRPP meetings already since the start of the month, and no further assembly has been scheduled. As the year unfolds, Bo Kyi says that the CSRPP will continue to identify and advocate for the release of all political prisoners, as soon as they reconvene.

“The committee needs to exist because we are not finished yet,” he said.