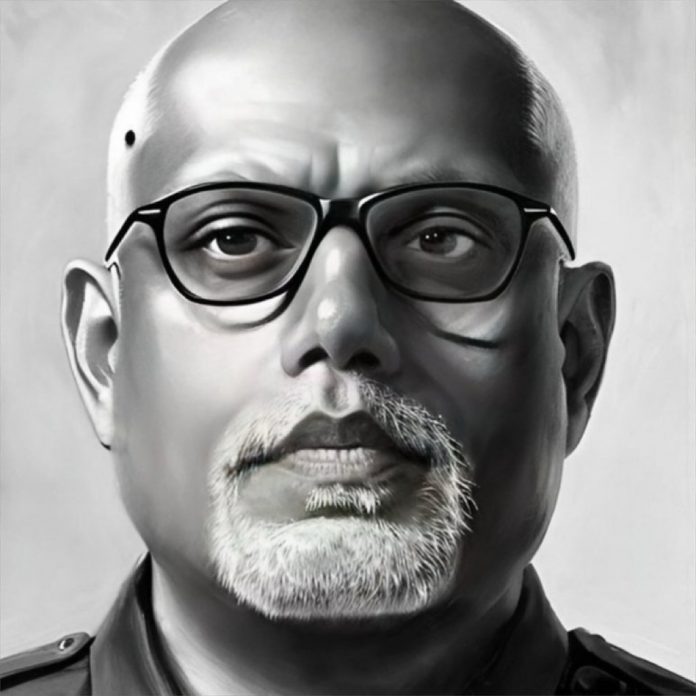

Guest contributor

Shafiur Rahman

The surging violence in Arakan State has opened a pandora’s box of political machinations, with key figures like Twan Mrat Naing, the Arakan Army (AA) commander-in-chief, and Khaing Thukha, the AA spokesperson, taking centre stage in an unsettling show of power.

Khaing Thukha’s pronouncements on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) and Radio Free Asia (RFA), along with Twan Mrat Naing’s BBC Burmese interview and social media posts, have cast long shadows across the landscape of community relations.

These are not isolated missteps but rather indicative of a pattern that serves to reinforce a singular narrative – one where the Rohingya are pawns in a greater geopolitical game of chess.

Just as disquieting has been the conspicuous silence from Rohingya diaspora spokespersons, and particular individuals who have historically been vocal and forthright in their advocacy for the Rohingya cause.

Let’s recap. The early months of 2023 have been tumultuous in Arakan (Rakhine) State, marked by a series of violent incidents, forced conscription, and significant impact on the Rohingya community and other civilians.

The international community, represented by voices like the U.N. Secretary-General and the U.N. International Children’s Fund (UNICEF), has expressed alarm over the escalating violence and its impact on civilians, particularly the Rohingya.

Violence has significantly escalated since last year unaffected by the China-brokered ceasefire on Jan. 11 between the Myanmar military and the ethnic rebel Brotherhood Alliance, but did not include Rakhine State. Since then, the AA has seized control of nine towns in Arakan State, as well as Paletwa Township in southern Chinland, as part of its offensive against the military.

Most recently, an airstrike in Minbya Township killed at least 23 Rohingya, including children, and injured many others. Similarly, artillery landed at Myoma market in Sittwe killing 12 civilians and injuring 30 others. On March 9, artillery landed in a Rohingya neighbourhood and killed at least five people.

Over 300,000 individuals have become Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Arakan State, with the total number of IDPs nationwide surpassing 2.8 million.

In Buthidaung and Sittwe townships, the military orchestrated a protest involving hundreds of Rohingya against the AA, using coercion and threats of violence.

Participants were reportedly transported to the town and forced, reportedly under the threat of having their homes burned down, to carry signs with messages reading “We don’t want war” and “No AA.”

The underlying message of the banners suggested that the arrival of the AA in their area would precipitate conflict.

Khaing Thuka acknowledged that the military orchestrated the protests in Buthidaung, in an interview with RFA. However, his subsequent criticism of the coerced Rohingya participants in the same interview is deeply contradictory.

His characterisation of the event as “one of the worst betrayals in history” disturbingly ignores the reality of the Rohingya’s plight, where the threat of violence looms large over any choice they might have.

Such a response suggests a wilful blindness to the coercive power exerted by the military and frames the victims as willing actors in this charade of propaganda, rather than as people manipulated by them into a display of allegiance.

Khaing Thukha’s assault on the Rohingya’s coerced participation in the protests is not only dismissive of the compulsion they faced but hypocritical given the broader political alliances within Arakan State.

While the AA and the military are engaged in conflict, it’s an oversimplification to ignore that a substantial segment of the Rakhine population, along with various political parties and political leaders (Aye Maung, Saw Mra Raza Lin), have found common cause with the military, be it for political expediency, strategic advantage, or survival.

The irony is profound within the Rakhine-dominated police and immigration services, where the majority, deeply integrated into the military regime’s apparatus, face no such accusations by the AA spokesperson.

This double standard further invalidates Khaing Thuka’s singling out of the Rohingya as betrayers. His condemnation, rather than challenging the regime’s manipulation, contributes to the rhetoric of division and undermines the collective struggle against the military’s oppression.

It is a concerning signal that, in the pursuit of their political objectives, the AA might be sidelining the very people they profess to protect.

If Khaing Thuka’s condemnation is a calculated manoeuvre in the high-stakes game of identity and allegiance in Arakan, then his boss, Twan Mrat Naing, has escalated the tension even further.

On social media, Twan Mrat Naing wrote: “Nothing is wrong with calling Bengalis ‘Bengalis’. They have been our neighbours, our friends and fellow citizens for centuries. Let’s be honest and embrace this reality to build a better future.”

In another post, he wrote: “As immediate neighbours, it is a fact that the Arakanese (Rakhine) ppl reside in Bangladesh as Bangladeshi citizens and there are ethnic Bengali citizens in Myanmar vice versa. However, some irrational individuals refuse to acknowledge the presence of Bengali ppl living in Arakan.”

In his remarks, Twan Mrat Naing deploys a strategy that is threefold, each element contributing to a broader narrative that distorts the complex plight of the Rohingya.

Through his choice of words, the shaping of historical context, and the framing of citizenship issues, he embarks on a course that significantly undermines the dignity and rights of the Rohingya community in three key ways:

By focusing on the supposed rationality of calling the Rohingya “Bengalis” and accusing dissenters of irrationality, Twan Mrat Naing’s statement overlooks the genocidal consequences of such identity politics. He disregards the severe human rights abuses and atrocities the Rohingya face, which are intimately connected to the denial of their identity.

The genocide against the Rohingya is marked by systematic efforts to erase their history, culture, and very existence in Myanmar – a reality that demands acknowledgment and action, not dismissal under the pretence of embracing a shared history.

By insisting on the term “Bengalis,” he denies the Rohingya’s distinct cultural, historical, and social identity, deeply rooted in Arakan for centuries. This denial transcends a mere terminological dispute. It dismisses their legitimate claims to belonging and rights within Myanmar.

By framing the issue as a straightforward matter of citizenship and cross-border presence, Twan Mrat Naing overlooks the impact of colonial and post-colonial policies on the region’s demographics and political struggles.

He is deliberately choosing to ignore the British colonial administration’s role in altering the socio-political landscape and how post-independence Burma policies further marginalised ethnic minorities.

The current discourse surrounding the Rohingya and Rakhine needs to be contextualised within these historical manipulations to understand the roots of the conflict.

The Arakan Army leader’s statement fails to acknowledge these manipulations and their lasting impacts on inter-ethnic relations and the political struggles in Arakan State.

These narratives de-legitimise the Rohingya’s identity to justify exclusion, discrimination, and violence against them. This strategy mirrors historical patterns where political elites have manipulated ethnic tensions.

In short, the social media posts from the AA leadership contributes to these harmful narratives which have facilitated the ongoing persecution and marginalisation, read genocide, of the Rohingya.

The deafening silence of Rohingya spokespersons, particularly Tun Khin, Nay San Lwin, and Reza Uddin, in the wake of Khaing Thukha’s and Twan Mrat Naing’s disparaging remarks serves as an indicator of the large chasm between the realms of activism and geopolitics.

Recently back from a mission to Bangladesh aimed at recalibrating Rohingya youth perspectives on the Rakhine community and the Arakan Army, this trio now appears to be paralysed by the intense scrutiny that has followed.

Their silence in the face of AA rhetoric has left them exposed to criticism and the impression of being ineffective.

Their recent endeavours, which included earnest engagements in Zoom meetings and a particularly telling interview with Zita TV, were designed to persuade the Rohingya to adjust their stance towards the AA but this may have backfired.

Their predicament is further exacerbated by the complex dynamics of Bangladesh’s own strategic interests, a maze that these spokespersons must navigate. This is a task for which their advocacy experience may not have fully prepared them.

Nay San Lwin’s prior statement: “The military is trying to create racial riots as it is losing the war,” now seems lopsided, as he fails to directly address the “Bengali” epithet directed at his community from the AA.

Previously, he was extremely vocal about the use of the term ‘Bengali’, calling out all who dared to use it, including the Japanese ambassador, and demanding an apology.

Similarly, he criticised the Myanmar Times, referring to it as Myanmar’s Rwanda Radio and a “genocidal paper.” Yet, he has now fallen silent.

The AA stance, oscillating between derogatory terms and gestures of goodwill towards the Rohingya, exposes a facet of its strategy that could alienate allies and undermine its moral standing.

As recently as 2017, Twan Mrat Naing was using the derogatory term “kalar.” Yet his shift to extending Eid greetings and condolences for the assassinated Rohingya leader, Mohibullah, suggested a pragmatic evolution aimed at enhancing his international image and accommodating the realities of administering territory with Rohingya inhabitants.

His most recent stance raises doubts about the authenticity of the AA commitment to inclusivity and the potential for lasting peace.

His approach, particularly the use of language that contributes to the genocide narrative, could have lasting repercussions, deepening divisions and sowing distrust among communities that might otherwise unite against common adversaries.

Ultimately, the rhetoric of inclusion and unity could succumb to political expediency with the most vulnerable paying the highest price.

I reached out for comments from two of “the trio” but I did not receive a response. I also received no response from the AA leadership.

Shafiur Rahman is a documentary filmmaker working on Rohingya issues.

DVB publishes a diversity of opinions that does not reflect DVB editorial policy. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our stories: [email protected]