When the former UN chief Kofi Annan wrapped up his year-long probe into Burma’s troubled northwest on 24 August, he publicly warned that an excessive army response to violence would only make a simmering conflict between Rohingya militants and Burmese security forces worse.

Just three hours later, shortly after 8 p.m., Rohingya insurgent leader Ata Ullah sent a message to his supporters urging them to head to the foot of the remote Mayu mountain range with metal objects to use as weapons.

A little after midnight, 600 kilometres northwest of the country’s largest city Rangoon, a rag-tag army of Rohingya militants, wielding knives, sticks, small weapons and crude bombs, attacked 30 police posts and an army base.

“If 200 or 300 people come out, 50 will die. God willing, the remaining 150 can kill them with knives,” said Ata Ullah in a separate voice message to his supporters. It was circulated around the time of the offensive on mobile messaging apps and a recording was subsequently reviewed by Reuters.

The assault by Ata Ullah’s group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), was its biggest yet. Last October, when the group first surfaced, it attacked just three police border posts using about 400 fighters, according to Burmese government estimates. The Burma Army is now estimating up to 6,500 people took part in the August offensive.

Its ability to mount a much more ambitious assault indicates that many young Rohingya men have been galvanised into supporting ARSA following the army crackdown after the October attacks, according to interviews with more than a dozen Rohingya and Arakanese villagers, members of the security forces and local administrators. The brutal October response led to allegations that troops burned down villages, and killed and raped civilians.

The crisis in ethnically-riven Arakan State is the biggest to face Burma’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and her handling of it has been a source of disillusionment among the democracy champion’s former supporters in the West. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres appealed to Burmese authorities on Tuesday to end violence against Rohingya Muslims, warning of the risk of ethnic cleansing, a possible humanitarian catastrophe, and regional destabilisation.

Rohingya leaders and some policy analysts say Suu Kyi’s failure to tackle the grievances of the Muslim minority, who have lived under apartheid-like conditions for years, has bolstered support for the militants.

Major counteroffensive

The fledgling militia has been transformed into a network of cells in dozens of villages, capable of staging a widespread offensive.

Burma’s government has declared ARSA a terrorist organisation. It has also accused it of killing Muslim civilians to prevent them from cooperating with the authorities, and of torching Rohingya villages, allegations the group denies. The latest assault has provoked a major counteroffensive in which the military says it killed almost 400 insurgents and in which 13 members of the security forces have died.

Rohingya villagers and human rights groups say the military has also attacked villages indiscriminately and torched homes. The Burmese government says it is carrying out a lawful counter-terrorism operation and that the troops have been instructed not to harm civilians.

Nearly 150,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since 25 August, leading to fears of a humanitarian crisis. Some 26,750 non-Muslim villagers have also been displaced inside Burma.

Suu Kyi has said she would adopt recommendations of Kofi Annan’s panel that encouraged more integration. She has also previously appealed for understanding of her nation’s ethnic complexities.

In a statement on Wednesday, she blamed “terrorists” for “a huge iceberg of misinformation” on the strife in Arakan. She made no mention of the Rohingya who have fled.

Suu Kyi’s spokesman, Zaw Htay, could not be immediately reached for comment.

On Monday, however, he told Reuters Burma was carrying out a counterterrorism operation and taking care of “the safety of civilians, including Muslims and non-Muslims.”

‘Not how humans live’

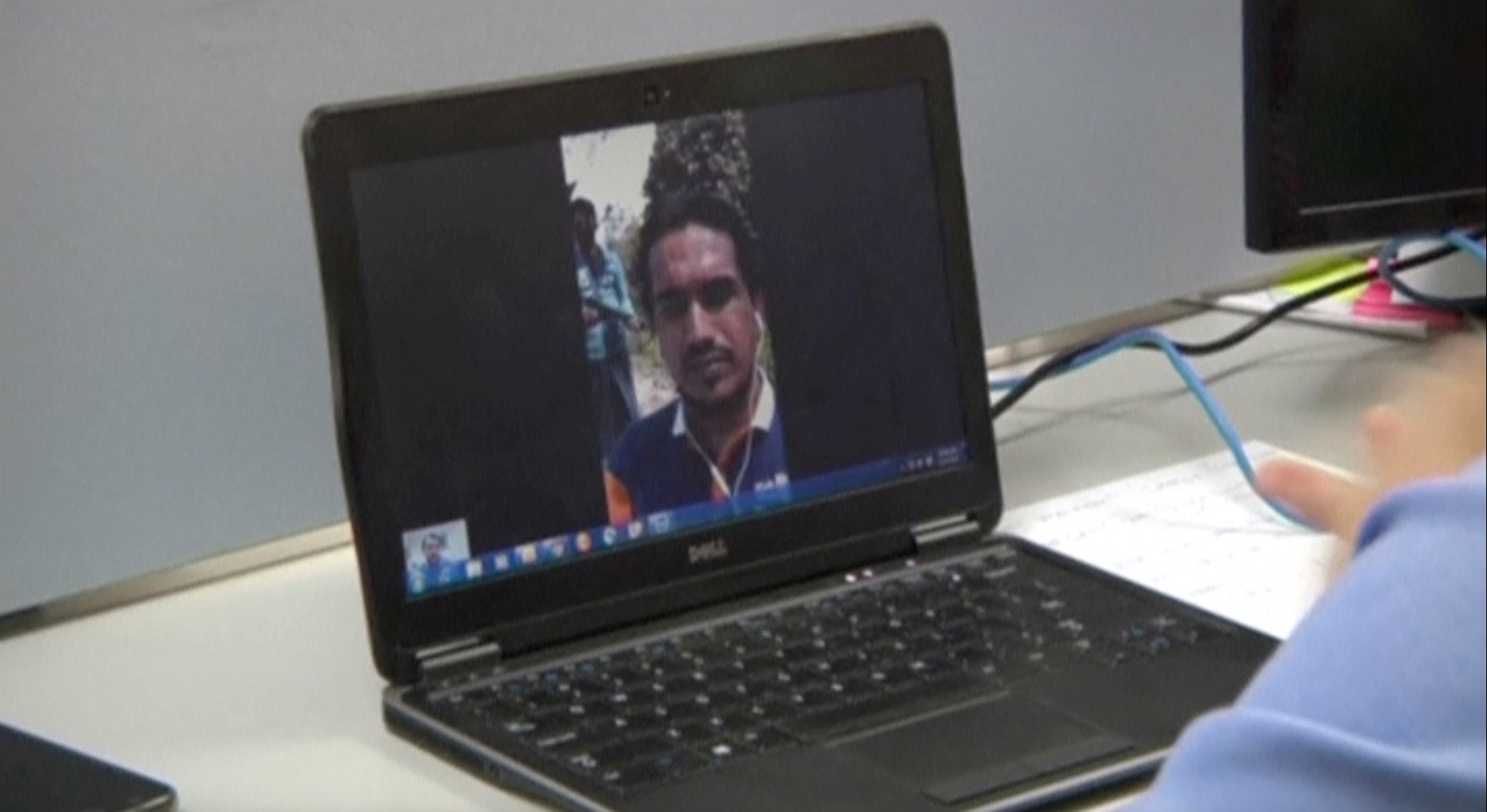

In an interview with Reuters in March, Ata Ullah linked the creation of the group to communal violence between Buddhists and Muslims in Arakan State in 2012, when nearly 200 people were killed and 140,000, mostly Rohingya, displaced.

“We can’t turn the lights on at night. We can’t move from one place to another during the day,” he told Reuters in previously unpublished remarks, referring to restrictions placed on the Rohingya population’s behaviour and movements.

“Everywhere checkpoints: every entry and every exit. That’s not how humans live.”

[related]

A Rohingya community leader who has stayed in northern Arakan said that, while the rest of Burma enjoyed new freedoms under Suu Kyi after decades of military rule, the Muslim minority has been increasingly marginalised.

Support for the insurgents grew after the military operation last year, he said.

“When the security forces came to our village, all of the villagers apologised and asked them not to set the houses on fire — but they shot the people who made that request,” he said.

“People suffered because their sons got killed in front of them even though they begged for mercy, their daughters, sisters were raped — how could they live without constantly thinking about it, that they want to fight against it, whether they die or not.” Reuters couldn’t independently confirm the villagers’ accounts. Last month, a Burmese government probe — led by former military officer and now vice president, Myint Swe — rejected allegations of crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing during the crackdown last year.

Cell network

Villagers and police officers in the area say that ARSA had since last October established cells in dozens of villages, where local activists then recruited others.

“People shared their feelings with others from the community, they talked to each other, they told their friends or acquaintances from different regions — and then they exploded,” said the Rohingya community leader.

Rohi Mullarah, a village elder from the Kyee Hnoke Thee village in northern Buthidaung Township, said the leaders sent their followers regular and frequent messages via apps like WhatsApp and WeChat, encouraging them to fight for freedom and human rights and enabling them to mobilise many people without the risk of being caught going into the heavily militarised areas to recruit.

“They mainly sent phone messages to the villagers, they didn’t … move people from place to place,” he said. He said his village was not involved in the insurgency and even posted a signboard in front of it that said any militants would be attacked by the villagers if they attempt to recruit people.

Many Rohingya elders have for decades rejected violence and sought dialogue with the government. While ARSA has now gained some influence, especially among young, disaffected men, many Rohingya elders have condemned the group’s violent tactics.

Campaign of terror

In recent months there had been reports of killings of local administrators, government informers and village chiefs in the Arakan region, leading to speculation the insurgents were adopting brutal tactics to stop information on their activities from leaking to the security forces.

“They cut out the government communication by instigating a campaign of fear and took charge in the region,” said Sein Lwin, police chief in Arakan State.

An army source directly involved in operations in northern Arakan also said it was now much more difficult to get information on ARSA’s plans.

The strategy resulted in the “shut down of government mechanisms” in some places “because no government servants dared to stay there,” the army source said. A village head from northern Buthidaung Township, who asked not to be named, said the insurgents called him several times pressing him to allow some young villagers to take part in their training — an offer he refused.

“I tried to stay safe and sometimes I had to sleep at the police station and local administrator’s house,” he said.

Intercepted messages

Despite the largely successful clamp down on information by the insurgents, it was a tip-off by an informer that stopped the 25 August attacks from being much worse for the Burmese security services, the army source said.

About an hour after Ata Ullah’s men headed for the jungle in the evening of 24 August, the army received a signal from the Rohingya informer saying the attack was coming.

The 9 p.m. message mentioned imminent multiple attacks, but it did not say where they would occur. The warning was enough for the security forces to withdraw some troops to larger stations and to reinforce strategic locations, saving many lives on the government side, the military source said.

The raids by the insurgents came in waves from around 1 a.m. until sunrise, and took place mostly in Maungdaw Township. This time, though, the distance between the northern- and southern-most points was as long as 100 km (60 miles). The Rohingya also struck in the north of the neighbouring Buthidaung Township, including an audacious bid to storm an army base.

“We were surprised they attacked across such a wide geographical area — it shook the whole region,” said the army source.