Germany’s media development agency DW Akademie hosted the Beyond Borders conference Oct. 31 to Nov. 3 in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Rohingya Maiyafuinor Collaborative Network co-founder Noor Azizah delivered the keynote speech.

Thailand hosts conference on forced migration in Asia

Myanmar looks more like ASEAN’s Syria than a democracy-in-waiting

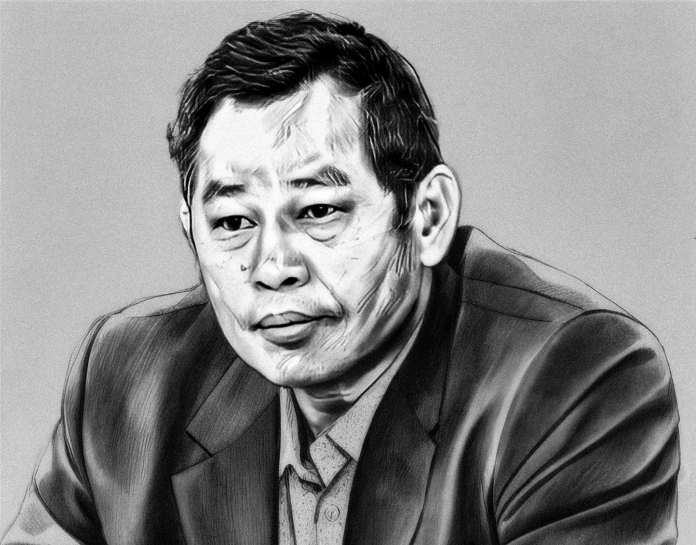

Guest contributor

Maung Zarni

Almost four years after anti-coup protests engulfed my birthplace, Myanmar under Min Aung Hlaing’s military junta looks more and more like Assad’s Syria in the wake of the United States’ failed color revolution. The escalating conflict in the ASEAN country has morphed into a brutal civil war.

Over the past year, anti-junta ethic armies have made significant military gains against the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s China- and Russia-backed military junta that seized power from Aung San Suu Kyi in 2021.

Myanmar’s armed conflicts are, tragically, no longer a simple, binary morality tale of good versus evil. Yes, the Tatmadaw remains the country’s largest armed organization and regularly commits atrocities. On their part, the anti-junta adversaries fighting “the common enemy” also perpetrate their fair share of atrocities against localized “enemy” ethnic populations.

Not all of these groups share an inclusive, democratic vision for the country of 55 million.

In October, Nicholas Koumjian, head of the United Nations Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar (IIMM), wrote that war crimes and crimes against humanity were “being committed with impunity across the country.”

Today, the violence in Myanmar is both vertical (the central state versus the rest of society) and horizontal (internecine ethno-communal conflicts), with different parties spouting political bromides like “democracy” and “revolution” to justify their violent actions.

Take Rakhine State. Civilians from all ethnicities in Rakhine have suffered, but especially vulnerable are the now stateless Rohingya people, who have been directly targeted in a slow genocide for over four decades.

Rohingyas who survived Myanmar’s state-organized genocide in 2017 have long been caught in what I call the “genocide triangle” in the shifting alliance between the Myanmar military and Islamophobic Rakhine Buddhist nationalists since the country’s independence in 1948.

According to the war-fleeing Rohingyas, anti-junta Rakhine groups like the Arkan Army (AA) have become the spearhead of a new wave of genocidal violence while talking up human rights.

“Once again, the Rohingya people are being driven from their homes and dying in scenes tragically reminiscent of the 2017 exodus,” said Agnès Callamard, secretary-general of Amnesty International.

“But this time, they are facing persecution on two fronts, from the rebel Arakan Army and the Myanmar military, which is forcibly conscripting Rohingya men.”

Alarmingly, on Burmese- and Rakhine-language social media accounts, supporters of AA publicly cheer on Israel’s ongoing genocide of “Muslim terrorists” in Palestine. Some of them express their admiration for the Jewish state as their Rakhine nation-building model.

The junta’s active campaign of mass conscription has also resulted in the panicked exodus of thousands of working age young men and women.

In collaboration with the Myanmar junta, Beijing has shut down China-Myanmar overland trade. Beijing is pressuring the anti-junta ethnic groups based in border areas to fall in line with its goal of ending the armed conflicts and reestablishing stability in Myanmar.

Consequently, the prices of essential commodities like rice, medicine, food and machine oil have surged. Chinese authorities have added to the misery by cutting off water, electricity and the internet in rebel-controlled border regions.

Are the junta’s battlefield and territorial losses, then, a win for multiethnic peoples? Yes and no.

Yes, because these regions are ancestrally non-Myanmar ethnic regions where the junta’s imposition of brutal military control for decades has generated so much local resentment.

No, because these armed groups have so far been unable to translate their military victories into policy victories that will bring communal stability (law and order), economic betterment, social and health services and education, and ultimately, an interethnic peace plan both within these regions and for the nation at large.

The junta’s retaliatory aerial bombings have also hampered any efforts to rebuild local institutions or start new community structures.

Worse still, the big picture of international power politics provides little hope for an end to this civil war.

China’s significant policy shift to back the unpopular generals could not have come at a better time for the junta. Beijing has enabled the junta to operate, at least within Southeast Asia, as a de facto state.

In October, the junta hosted the well-attended and important ASEANAPOL conference, while no U.N. member appears ready to recognize the anti-junta National Unity Government (NUG) as the country’s legitimate government.

Even under the chairmanship of Indonesia, ASEAN’s big actor, the regional bloc has proven incapable of moving beyond its Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar. ASEAN’s policy failure is due to its members’ conflicting interests and divisions over how best to help end Myanmar’s all-out civil war.

At the end of the Cold War, the U.S. was seen, rightly or wrongly, by many pro-democracy activists as a force for good.

Washington’s vicious global war on terror post-9/11, its failed attempt to build the unipolar world it planned to dictate and, presently, its unconditional support for Israel’s genocide and ethnic cleansing in Palestine has shattered the U.S.’ image as the white knight of human rights.

Today, Washington’s nominal backing of the Myanmar resistance has become both a moral and strategic liability. Understandably, China wants no group it sees as U.S. lackeys to be in power next door.

Recently, activists and artists from the predominantly Buddhist nations of Cambodia and Vietnam organized a solidarity event for the people of Gaza. Their conspicuous silence about the ongoing civil war in Myanmar, another predominantly Buddhist nation, speaks volumes about just how morally uninspiring Myanmar’s anti-junta resistance is.

No moral citizen of the world wants to support a resistance movement that demands human rights, freedom and democracy only for their own ethnic groups, but refuses to extend the same rights to Rohingya genocide victims.

Four years into the anti-coup movement, I have had the time and privilege to reflect on my early post-coup optimism. On March 26, 2021, I wrote an optimistic op-ed in The Washington Post, shared my hope for a better future in Myanmar with the BBC World Service, and argued confidently that a post-Aung San Suu Kyi Myanmar was going to be morally different.

I believed that the Nway Oo Revolution, or Myanmar Spring, and its multiethnic armed resistance, which I supported financially and otherwise, would usher in an era of progressive change and transform my homeland into an inclusive society.

Alas, my optimism has been proven rather premature. Last week, U.N. Special Envoy for Myanmar Julie Bishop pointedly told a U.N. General Assembly committee: “Myanmar actors must move beyond the current zero-sum mentality. There can be little progress on addressing the needs of the people while armed conflict continues across the country.”

Myanmar people who care about the country’s future must swallow the bitter pill of reconciling with those they view as “enemies”. Otherwise, our strife-torn country will become permanently fractured, like Assad’s Syria.

Maung Zarni is the co-author of Essays on Myanmar’s Genocide of Rohingyas (2012-18). He is a UK-based Burmese exile with over 30-years of first-hand involvement and scholarship in Burma affairs.

DVB publishes a diversity of opinions that does not reflect DVB editorial policy. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our stories: [email protected]

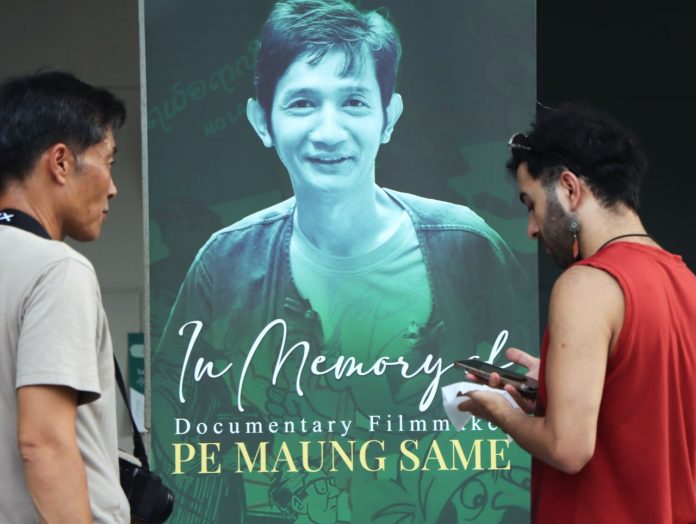

Human Rights Lens – Episode 10: Myanmar’s political prisoners

Human Rights Lens – Episode 10 investigates the treatment of Myanmar’s political prisoners. It’s brought to you by the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) and the National Unity Government (NUG) Ministry of Human Rights. It is co-presented by the NUG Minister of Human Rights Aung Myo Min.

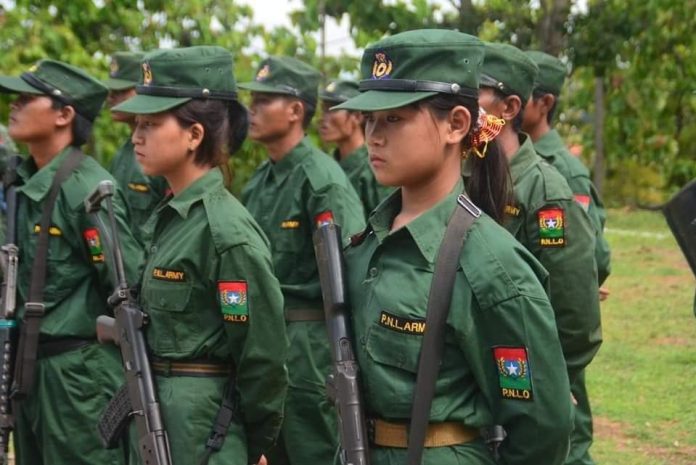

What’s happening in Myanmar’s Pa-O Self-Administered Zone

In southern Shan State’s Pa-O Self Administered Zone, two ethnic armed groups have taken sides since the 2021 coup. One is fighting alongside the military, while the other has joined the resistance. But a split in the resistance has one faction willing to fight the military and the other wanting to continue negotiations with the regime in Naypyidaw.

Regime nationwide census faces deadly consequences

At least 43 people were killed by anti-coup resistance forces after they had warned civilians against assisting or participating in the regime’s nationwide census last month. Naypyidaw stated that the census was conducted with 40,000 workers in order to compile voter lists for elections tentatively scheduled for November 2025. Myanmar’s previous census was held in 2014.

The Oct. 1-15 census was later extended to Oct. 31. Among the dead were 35 military personnel and police officers, five administrative staff, and three teachers. Pro-democracy activists warned citizens against participating in the census, adding that it’s an attempt by the regime to gather personal information.

The military detained around 40 people in connection with attacks on census workers, while resistance forces state that they had arrested 20, including administrative staff, education workers, and other people they accuse of collaborating with the regime.

Resistance forces claimed to have carried out 36 attacks during the census with incidents reported in Sagaing, Mandalay, Tanintharyi and Bago regions. Five administrative offices were attacked in Yangon Region. The regime has denounced all attacks and arrests as “terrorism.”

Fifteen soldiers were killed en route to collect census data by the People’s Defense Force (PDF) in Yamethin Township, which is located 54 miles (87 km) north of the capital Naypyidaw and 125 miles (201 km) south of Mandalay.

Legal expert Kyi Myint questioned the regime’s authority to conduct a nationwide census, given that it went against the 2008 constitution when it seized power after the 2021 coup. “Min Aung Hlaing has no authority to hold elections or emergency powers. The census collection and related activities are just deceptions and are illegal,” he told DVB.

The regime announced that it has collected census data from approximately 13 million households. However, data was not collected from areas under PDF or ethnic armed group control. The U.N. states that there are 3.4 million Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) who have fled their homes, mostly due to conflict.

The National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory in the 2020 general election, which was held four years ago today, on Nov. 8. The military justified its coup on Feb. 1, 2021, claiming that there were widespread voting irregularities. International organizations have found no evidence of this and declared the election results largely free and fair.

The Mon State Federal Council, which represents resistance groups in Myanmar’s southeastern state, opposed the regime census and said it will also oppose any regime-run election next year.

“Our main opposition activities will prioritize preventing political parties from participating in the fake election, preventing campaign activities, discouraging people from voting, and preventing polling stations and elections from operating,” said Thiri Mon Chan from the Mon State Federal Council.

Cyber scams operating again near Myanmar-China border

Cyber scam compounds have expanded into new areas of Myanmar’s Shan State, following a crackdown on operations near the Myanmar-China border in February. These illegal activities have been established in four townships under both regime and ethnic armed group control in Shan State.

“There are more than three major scam centers with hundreds of employees,” a resident of Tangyan Township, located 83 miles (134 km) southeast of Lashio in northern Shan State, told DVB on the condition of anonymity. Residents claim these operations are protected by regime authorities, including soldiers, police, and administrators.

Cyber scam compounds were set up in Tangyan in 2023 after a crackdown in Panghsang (Pangkham), the capital of Wa State – officially known as the Wa Self-Administered Division – an autonomous zone administered by the United Wa State Army (UWSA) along Myanmar’s borders with China and Thailand.

“They’re all involved. It’s devastating our youth—some have even died from drug abuse,” a Tangyan resident told DVB.

On July 11, the UWSA deployed thousands of its troops to Tangyan “to prevent the spread of ongoing conflicts” and to protect its interests in northern Shan State.

Jason Tower, the Myanmar director for the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), told DVB that cyber scam compounds in Tangyan are under the protection of the UWSA.

“Tangyan is notable because it’s a township where the Myanmar military agreed to the UWSA coming in. There’s essentially a form of joint governance going on between the military and its remaining forces in Tangyan and the UWSA,” said Tower, who has been monitoring the spread of cyber scams across Myanmar.

Cyber scam compounds have also relocated to areas under the control of the pro-military Mong Ha militia in Mongyai Township, which is located around 56 miles (90 km) south of Lashio. Mongyai town has been occupied by the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP/SSA) since July.

“When the scam sites were being cracked down on the Chinese border, a group moved into the territory of the Mong Ha people’s militia,” a Mongyai resident told DVB on the condition of anonymity. “They’ve set up operations near Man Kyu village. They employ about 3,000 people.”

The regime in Naypyidaw reestablished its Northeastern Regional Military Command (RMC) headquarters in Mongyai after the Brotherhood Alliance, which includes the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Arakan Army (AA), took control of Lashio on Aug. 3.

“The cyber scam sites are operating around 25 miles [40 km] from Mongyai town. They coordinated with [Myanma Posts and Telecommunications] to extend fiber optic lines there for internet access,” another Mongyai resident told DVB.

Scam compounds have reportedly been set up in the village of Wanhai, which is 43 miles (69 km) south of Mongyai in Kyethi Township. Wanhai serves as the headquarters of the SSPP, which is an ally of the UWSA.

Chinese cyber scam operations have also been established in Laihka Township of southern Shan State, which is located around 89 miles (143 km) east of the Shan State capital Taunggyi.

The cyber scam compounds are guarded by pro-military militias. A Laihka resident told DVB that the its workers have caused the price of essential commodities to surge in the township.

Cyber scams have expanded in Myanmar since the 2021 military coup along its 1,370 mile (2,204 km) border with China, according to the U.N.

Relations between Beijing and Naypyidaw have been strained as many Chinese nationals were trafficked and forced to work at the compounds in areas controlled by militias loyal to the regime.

Many Myanmar-China political analysts believe that Beijing gave its tacit approval to the Brotherhood Alliance to launch Operation 1027 on Oct. 27, 2023 over Naypyidaw’s failure to crack down on cyber scams along the border.

Min Thein, regime ambassador to Austria, claimed during the 12th U.N. Convention against Transnational Organized Crime held in Vienna earlier this month that Naypyidaw has taken action to crackdown on cyber scams in Myanmar.

But according to a report released last month by USIP, operations in Myanmar have accelerated over the past year.

“What’s interesting here is that we’re seeing trends that kind of parallel what has happened with narcotics more broadly in that China asserts pressure immediately on its border [in northern Shan]. Other actors respond by shifting a lot of that production to the south,” added Tower.

At least 120,000 people across the country may be held in areas where they are forced to carry out online scams, added the U.N.