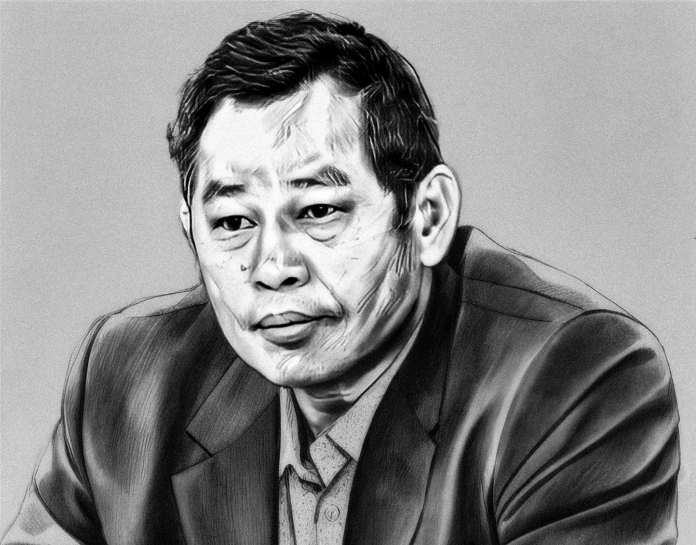

Guest contributor

Maung Zarni for FORSEA

In any history, there are certain events which produce a seismic impact on the course of a country or a people’s future. For the people of Myanmar, that event has to be the July 19, 1947 assassination of Aung San (then aged 32) and half of his pre-independence cabinet of people coming from a multi-ethnic and multi-faith background.

Specifically, Aung San and his post-World War II colleagues succeeded in hammering out the twin framework for the nature of the post-colonial political state, namely federalist power-sharing arrangement, which recognized the right of self-determination of ethnic communities, and an inclusive citizenship framework, which was anchored in both the idea of indigeneity and the status of local residency a decade priority the end of the pre-World War II British rule in 1942.

With the benefit of the hindsight of 77 years, I for one trace the origin of Myanmar’s unfolding internal Balkanization, albeit without the emergence of new republics or alteration of external boundaries.

Both civilian politicians with huge sway over the dominant ethnic Bamar and the three generations of military leaders who have instituted and maintained a military dictatorship since 1962 have discarded, in spirit and in deeds, the country’s founding principles of ethnic group equality and the inclusivity in granting equal and non-tiered citizenship to all persons, irrespective of race, faith, and creed.

During the first military dictatorship of General Ne Win from 1962 to 1988, Rohingya suffered the blatant denial of their citizenship and official ethnic inclusion as an integral community of multi-ethnic Union of Burma. The 1982 Citizenship Law created, in effect, an apartheid system of tiered citizenship, wherein the fascist-inspired idea of “blood-based” citizenship was elevated at the expense of equally valid historical residency.

Consequently, the non-Rohingya public, both the Bamar majority and other indigenous public, typically referred to as “Taiyintha” sleepwalked, as cheerleaders (and collaborators, in the case of Rakhine Buddhists), into the military-initiated decades-long persecution. My scholar colleague Natalie Brinham (pseudonym Alice Cowley) and I sounded alarm over this breach of international law and civilizational norms with our three-year study: “The slow-burning genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingya” (2014).

Three years on in the fall of 2017, this persecution climaxed into a textbook example of genocide, resulting in the exodus of nearly one million Rohingya – and countless deaths and destruction of over 300 villages and neighbourhoods in northern Rakhine (Arakan) State, at the hands of the Myanmar Armed Forces, aided and abetted by local anti-Rohingya Rakhine collaborators.

By 2019, the state of Myanmar was hauled before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the principal judicial organ of the U.N., for its alleged breach of the inter-state treaty called the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide.

Then in her capacity as State Counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of the martyred national leader Aung San, represented Myanmar as a state party to the Convention to defend what she calls with pride and public affection: “My father’s army.”

As if it hadn’t ever perpetrated genocide. She dismissed any allegations and evidence of the military’s mass rape against hundreds of women whose identity as ethnic Rohingya she categorically refused to recognize.

Suu Kyi’s attempted erasure of the victims’ group identity is a part and parcel of a textbook genocide, from Palestine to Myanmar. It is in breach of an ethnic group’s right to self-identify and against the mountains of official and historical documentation of Rohingya presence and identity in Myanmar.

In November 2017, I had travelled to Rohingya genocide survivors’ camps in Bangladesh and recorded in-person interviews with over a dozen Rohingya women who survived or witnessed the rape in Rakhine State across the land and river borders from Bangladesh. I knew the daughter of my role model and hero, both childhood and to this day, Aung San was lying through her teeth.

A word about Aung San.

Born in the ethnic heartlands of the Dry Zone (or Upper Burma) in 1915 to a small land-owning family, the young student anti-imperialist agitator-cum-Marxist revolutionary leader, was a self-made man who lived his singular dream of liberating the colonized society of multi-ethnic peoples, both those who claimed indigeneity and who adopted colonial Burma as their homes.

He drew his inspiration in defining who belonged in the country not from the blood-anchored conception of a Burmese or non-Burmese indigenous person, but from the progressive citizenship definitions of both the USSR and U.S. In his widely listened to public addresses, he made his radical post-ethnic/-racial definition of “taiyintha” or “children of the soil” as anyone who adopted the country, expressed his or her concerns for the collective welfare of all people and contributed to the country’s progress.

In a country where the majority Bamar possessed fascist and authoritarian tendencies, which were publicly pointed out by Thakin Ba Hein, Aung San’s peer at Rangoon University in the 1930s and subsequently the general secretary of the Communist Party of Burma, a small band of Marxist-inpired university-educated revolutionaries, including Aung San, broke free of these psycho-cultural impediments. They attempted to advance the non-racist and non-authoritarian conception of political citizenship – and ethnic group equality among the soon-to-be independent colonial Burma.

I learned first hand about these two remarkable revolutionaries from my great-uncle who was classmates and friends with both Aung San and Ba Hein. Between the two leaders, who headed the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) and the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), Ba Hein died first a natural death in my old high school in Mandalay, which was converted into a World War-time hospital by the occupying Japanese fascist authorities.

Months later, Aung San and his multi-ethnic colleagues were gunned down in a successful assassination plot during the mid-morning cabinet meeting. Despite the overwhelming evidence of Britain’s involvement, from multiple credible sources, U Nu, Aung San’s deputy and vice president of the AFPFL, and his colleagues attempted to conceal the instrumental role the British played in eliminating the most influential Burmese nationalist politician, who publicly talked about the intention of his post-colonial government to nationalize resource extractive industries such as oil and mining, as well as other strategic economic sectors.

In terms of Aung San’s national political program, he succeeded in persuading different ideological and ethnic representatives – who represented socialist leaning new ethnic masses, the centuries-old feudal ruling houses from the hill areas of western, northern and eastern Burma and tradition-bound Bamar nationalists with feudal outlook – to work together voluntarily and forge the former colony as a federalist democracy, an unprecedented historical vision.

The late Maha Devi (or chief queen) Sao Naw Hkan of the ruling house of Yaunghwe, southern Shan State wrote to her American friend and the resident economic adviser to U Nu’s Government named Louis Walinsky, that “it was Aung San who in fact offered the right of secession or self-determination in Panglong,” which is the founding treaty among different ethnic groups.

Apparently, Aung San wanted to convince the ethnic representatives who gathered at a small hill station town of Panglong hosted by her husband, Sao Shwe Thaike, that he meant business when he offered ethnic group equality.

I read the letter when I was sorting out the Burma collection after our mutual friend Lou’s death in Washington, DC. [She was the mother of Harn Yaunghwe who directs the Euro-Burma Office and advocates for peaceful political negotiation in the federalist spirit of Panglong as a way to end the 70-years of civil war raging with fluctuating degrees of ferocity.]

But Aung San’s federalist and democratic vision has had one big problem.

Neither his successor, the late Prime Minister U Nu, nor his own surviving daughter Aung San Suu Kyi shared this commitment to ethnic group equality. In a type-written copy of the Burmese language letter (dated 2 March 1973) – in my possession – written to his anti-military dictatorship armed comrades, when he was the figurehead, U Nu confessed that from the day he became the post-Aung San leader of independent Union of Burma he was opposed to the right of self-determination of any ethnic group, in direct breach of both the spirit and letter of the Union of Burma’s founding treaty of Panglong.

The 1947 Constitution of the Union of Burma, completed under Nu’s pre-independence leadership and after Aung San’s assassination in 1947, was “federal only in name, but unitary in substance.”

The late Chan Tun, the Cambridge-trained barrister and Aung San’s legal adviser on the constitution drafting committee, admitted this sordid fact to the late Edward Law-Yone, the chief editor of the then influential English daily, The Nation, in the 1950s when the discontent and strife over the unequal ethnic group relations were beginning to surface.

As a matter of fact, U Nu’s refusal to honour this group equality principle fractured the emerging armed resistance coalition of ethnic Bama, Mon and Karen movements with the common aim of ending General Ne Win’s dictatorship.

General Ne Win ousted the U Nu government in 1962, and jailed him for five years, after which he left the country and joined the armed resistance movement established along the Thai-Burma border by the likes of Law-Yone and other liberal democrats.

Likewise, despite the initial embrace and popular support among non-Bamar or – Burmese ethnic communities – which make up 30 to 40 percent of the country’s total population – Aung San Suu Kyi proved herself to be a Bamar and Buddhist nationalist, who treated representatives of other non-Bamar ethnic communities – and religious minorities – with stomach-turning condescension, barely concealed contempt and apparent ethnic chauvinism.

Today Myanmar’s plunge into the ferocious civil war is accelerating in various ethnic regions – from the coastal Rakhine and hilly Chin states on the western frontiers to northern Myanmar’s Kachin highlands, Shan plateau, Karenni, Karen and Mon states along the border regions.

The public is now waking up to the ugly reality: the territorial gains by the anti-dictatorship resistance organizations vis-à-vis the genocidal Myanmar national military do not signify a new, progressive and emancipatory political future for either the locals under the Arakan Army, the Kokang (ethnic Chinese) Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, the United Wa State Army, and so on, or the country at large.

On the contrary, the intra-minority group rifts and tensions are brewing as the military victorious “ethnic resistance organizations” are promoting their respective strains of ethnic-supremacy, whatever their name, with the exception of the Karen National Union and the Karenni National Progress Party.

Absent any inclusive, post-ethnic political framework that guarantees group equality (or federalist arrangement) among ethnic communities whose presence is now interspersed across different mono-ethnically named regions, commitment to universal human rights and democratic principles, Myanmar is heading towards a hybrid between dismembered Syria and the ethnically poisonous post-Yugoslavia states.

Of course, unlike the disintegration of Tito’s Yugoslavia which resulted in new republics allied with different external geopolitical powers such as Russia, the U.S., the EU and, (to a lesser extent, China), the late Aung San’s Union of Burma will remain a permanently divided society of overtly racist populations within its external boundaries primed for strategic exploitation via their local ethnic proxies, by different external actors such as China, India, Thailand, and the U.S.

On 6 August, my fellow co-founder Ro Nay San Lwin of the Free Rohingya Coalition alerted the world of rights activists, journalists and government officials to the video evidence of the Arakan Army’s latest genocidal slaughter of over 200 Rohingya children, men and women in his native northern Rakhine state. Neither Myanmar’s anti-military National Unity Government (on Zoom) nor any Ethnic Armed or Resistance Organisation have spoken out.

Not a single Myanmar language media outlet has covered this atrocity crime. Apparently, an anti-resistance group fighting for their own ethnic group’s freedom is committing atrocity crimes against Myanmar’s defenseless genocide survivor community of Rohingya is not deemed newsworthy to Myanmar journalists.

Myanmar today is home to multiple racisms, ethnicity-based violence and armed movements, conflicting commercial interests and territorial claims, multiple chains of command, countless armed groups.

You can kiss goodbye to a federalist democracy, with human rights.

Maung Zarni is a UK-exiled scholar and revolutionary from Burma with 35 years of direct political involvement in Burmese affairs.

DVB publishes a diversity of opinions that does not reflect DVB editorial policy. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our stories: [email protected]