The Ethnic Community Development Forum (ECDF) released a statement on Thursday which slammed Burma’s draft National Land Use Policy for failing to protect small-scale farmers and ethnic minorities—in part because the policy’s approach to “virgin lands” overlooks traditional shifting agricultural practices of certain ethnic groups in Burma.

In its statement, the coalition of local ethnic NGOs said, “We do not accept the land classification of ‘Vacant, Fallow, Virgin Land.’ There is no [such land] in ethnic territories.”

The Burmese government seems to think otherwise, and is planning to convert what it considers “wasteland” into “productive” land by selling it to large-scale agriculture and industrial companies.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation has created a “30-year Master Plan” which it hopes will encourage foreign investors to transform 10 million acres of “wasteland” into textile factories and rubber, palm oil and cassava plantations.

The idea is to use Burma’s cheap labour force and supposedly ample supply of “unused” land to mass produce exports for its three large neighbouring markets: China, India and ASEAN.

Danny Marks, a PhD Candidate at the University of Sydney who has researched smallholder agriculture in Southeast Asia, told DVB that the National Land Use Policy is just another way of legitimising the government’s master agricultural plan—a process that could destroy the livelihoods of millions of small-scale farmers.

“It’s a shame that the draft Land Use Policy gives higher priority to the interests of foreign investors than smallholder farmers even though smallholders are the backbone of Myanmar’s [Burma’s] economy. This policy could ignite already-existing social discontent among smallholder farmers,” he said.

Marks also said the draft policy is driven by short-term economic interest, and that “in the long run, it will worsen food security and degrade the country’s environment.”

According to a paper written by Kevin Woods, an expert on Southeast Asian resource politics at the Transnational Institute (TNI), the draft land use policy will serve as a blueprint for the third major land law passed by Burma’s quasi-civilian government. Woods indicates that these laws—coupled with Burma’s generous foreign investment rules—are designed to dispossess local farmers from their land in favour of foreign investors. He also indicates that Burma’s land law regime will only perpetuate a process that has been going on for years.

Wood’s paper, entitled “The politics of the emerging agro-industrial complex in Asia’s ‘final frontier’,” says that as of March 2012, the government had allocated 3.5 million hectares of land to local agribusiness companies—the vast majority of which were affiliated with the Burmese military. During this “allocation” process, Woods notes that smallholder farmers were forcibly evicted, received scant compensation and were even arrested for protesting.

[related]

Recently, many farmers have attempted to fight back by engaging in “plough protests,” whereby they grow crops on land which the military previously confiscated from them. DVB has covered several of these protests, and often times the protestors have wound up in prison.

In August, for example, local farmers from Mandalay Division’s Sintgai Township were sentenced to eight months’ imprisonment for trespassing and destroying property during a plough protest.

According to the ECDF statement, another sticking point is that large-scale development projects continue to be launched in many ethnic areas where ongoing armed conflict has already ravaged communities. These projects also have a tendency to exacerbate old conflicts and spark new clashes.

Perhaps the most destructive example of the latter situation is the role played by the Myitsone Dam in sparking widespread conflict in Kachin State. In the past few years, NGOs have issued multiple statements and reports condemning large-scale development projects for destroying local ecosystems; forcing people off their land; and damaging ethnic communities in various ways.

The Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) issued a report in May which documented a rising number of landgrabbing cases in southeastern Burma following the 2011 ceasefire between the Karen National Union and the Burmese army—a phenomenon which the NGO attributed, in part, to large-scale development projects in the region.

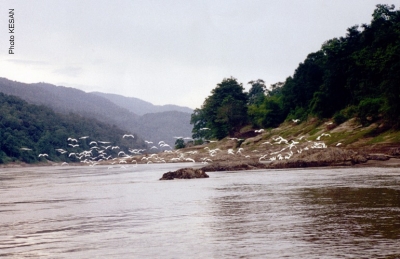

In its report, KHRG cited the Hatgyi Dam as just one of several examples in which development projects have incited conflict and displaced locals from their land. In an article published by the Karen News Group (KNG), the KHRG report was cited as saying the following:

“Armed conflict broke out between [government-allied border guard forces and Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA) soldiers] over the Hatgyi Dam in 2012, which caused villagers to flee and be displaced from their homes for a short period of time. Because of land confiscation, tens of thousands of villagers have been displaced and communities face increasing water contamination and damage to land because of development projects.”

KNG also reported in September that a coalition of local NGOs in Shan State called for a moratorium on large resource-extraction projects after locals complained that one project had “contaminated the water supplies of nine villages in the area and destroyed 100 acres of farmland because of pollution.”

The draft National Land Use Policy appears to address some of these problems by proposing a “temporary suspension of investments which require land acquisitions” until the policy is approved, but ECDF says the draft’s focus on “investments which require land acquisitions” is actually a red-herring that ignores the larger problem.

Instead of suspending just one subset of projects, ECDF insists there is an “immediate need … to postpone all … investments in ethnic areas during the current national reconciliation and peace-building process” in order to avoid further land conflict.

In its statement, ECDF said it rejects the draft policy on grounds that it was drawn up without sufficient public input. The government gave the public three weeks to submit comments on the draft, but ECDF believes this time period was not long enough given the length and complexity of the document—not to mention the lack of a political atmosphere conducive to open dialogue. As a result, the NGO coalition said that many important stakeholders did not have a meaningful opportunity to participate in the process.

In particular, ECDF said the land use policy was drawn up without consulting small-scale farmers, ethnic groups, women and others who are liable to suffer if the draft policy is approved.

Speaking to DVB by telephone, Danny Marks said, “The three-week time period was just too short. The government should have had meaningful public consultations and allowed smallholder farmers to suggest amendments because they’re the ones who will be most affected by this policy.”