Keeping ancient Shan medicinal practises and civil society alive in Thailand.

Ajarn Monglee Suriya doesn’t claim to have any supernatural powers. He doesn’t claim he can speak to ghosts or exorcise demons. Monglee is a medicine man who reads from an ancient textbook and makes diagnoses through mathematical calculations.

The interweaving practises of Horasart, numerology and palmistry are an ancient art of reading the past and foretelling the future throughout different spiritual realms. Popularity is slowly fading among the Shan peoples, particularly migrants, as they are increasingly absorbed into Thai culture and exposed to western medicine.

However, Ajarn Monglee remains a popular man in the Shan migrant community of Chiang Mai, where he acts as a leader of the Shan cultural preservation effort. He’s even beginning to gain a following among local Thai’s as word of his successful predictions spreads.The practise dates back to pre-Buddhist times, some suggest that the basic framework for palmistry finds its roots in ancient Greek mythology. Having traversed it’s way to east Asia over millenniums, the story of the Buddha’s mother having her palm read is commonly told to children by many Buddhist groups today.

Two decades ago and 800 kilometres away Ajarn Monglee (“ajarn” meaning “teacher” in both Shan and Thai) fled his home in Pang-yang in northern Shan State for Thailand when a Burmese army offensive reached the neighbouring towns of Konhein and Minesho. “If we’d stayed we would have died,” he said. “The Burmese came and shot everybody, even the monks and the women.”

While the regime in Burma doesn’t specifically target Buddhists, religious leaders from minority groups often find themselves at particularly high risk as they act as community leaders. As well as their religious practises, this civil structure of leadership within a community has found it’s way to Thailand as well.

Tucked away behind a main road in central Chiang Mai, Soi Sanam is a small, well-hidden but densely populated alleyway home to around 300 Shan migrants from Burma who have permanently settled in the city. Few Thai people know of it. The alley is only about 4 metres wide and 200 metres long, just wide enough for a car to pass through. Those who reside here make up one of the most solidly established migrant communities in the city, which is host to a plethora of minority groups.

As a young boy Monglee was trained by his grandfather in Horasart back in Shan State and began practising for the local Shan migrant community on Soi Sanam in around 1988.

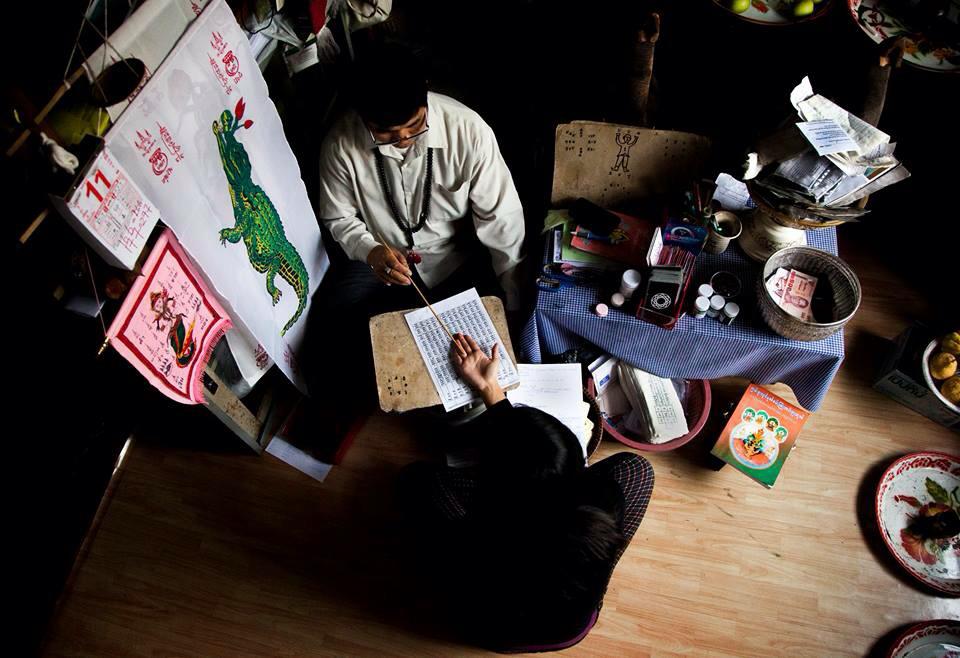

Today Ajarn Monglee, in his dark cluttered upstairs room, sits beside his musty shrine. The heavy smell of joss sticks hangs in the air creating an ethereal, hypnotic atmosphere. Across from him sits a young Thai woman, Chonlada. He begins by asking her date and place of birth before consulting a birth chart to find the precise day she was born, which delivers a number from one to seven. Next, a complex series of calculations revealing Chonlada’s past medical history and future health.

Chonlada sits for the reading quietly, only breaking her silence to murmur, “yes” in agreement with his specific recollections of her past ailments.

Patrons also come for general guidance – today it’s career advice. Ajarn Monglee reads Chonlada’s palm, which reveals further number sequences.

“Keep moving forward, for now follow the money. Later on in your life you’ll have financial issues so make as much as you can for now and save while you still have a chance.” Monglee claims that at age forty-two Chonlada will face her financial struggles, but adds, “you’ll be out of misery by the time you’re sixty-two.” Monglee speaks in a calm, direct matter-of-fact voice throughout. “Also you’re suited for education jobs, so maybe go in that direction.”

He asks Chonlada if she’s interested in her past life- she faintly nods in reply. Rather specifically he declares, “In your last life you were an elephant until your death, then you wandered as a forest spirit, after your death you befriended a monkey ghost who took your spirit to your mother.” Monglee suggests she should make a green bag to better connect with that part of her life, Chonlada gives a deep nod of contemplative understanding.

There is a certain vividness and attention to detail to Monglee’s claims, this perhaps is why he’s achieved such a large following. His customers believe he holds a certain aura and can bestow blessings. However, he says modestly, most of his advice comes from the book handed down to him from his grandfather. The origins of the book are a mystery, one that Monglee is keen to uphold, or perhaps he doesn’t know himself.

Ajarn Monglee pulls up his sleeves to reveal his heavily tattooed arms. The print is a combination of Shan and Thai, each line of text a different prayer or good-luck charm. The Shan people began tattooing religious texts on their bodies in the 15th century, when the Chinese invaded and burned the Shan holy books.

These tattoos are still popular among pious Shan men today. However, they cannot be read out loud for the sake of translation, as the prayer must not be said in vain, only when asking a favour of the gods.

Downstairs the family have gathered for a portrait at the clothing shop run by Ajarn Monglee’s wife, all dressed in traditional formal Shan clothes. Lining up, 10-year-old Chorkhun stands quietly at the front. Chorkhun is destined to inherit his father’s position. He flashes nervous glances towards the camera, always shuffling in his slightly oversized slippers.

Members of the local community chatter as they congregate behind to watch. “They come to me for anything I can help them with. If anything is bad, I can help make it better. Any secrets, illness- it can all be revealed by the palm and the numbers.”

“I specialise in medicine but also advise them on cultural teachings, religious matters, financial advice, education, career, anything. Many Thai’s come too, I’ve even had some Westerners,” he says.

To hold the position of Ajarn in a community is a great honour, and it means more than just ‘teacher’. The Ajarn in a community is often the unofficial leader, much like a village chief.

It’s remarkable that this small Shan community have picked themselves up from across the vast Shan region and relocated, not just themselves, but an entire religious and social order into the centre of one of Thailand’s largest cities. By doing so, they have kept alive a culture that has been under threat for generations.

[related]

Ajarn Monglee returned to Shan State for the first time three years ago. “The shootings have mostly stopped, but Burma today is still not much better than it was,” he says.

Over the past two decades the community in Soi Sanam have thrived in Chiang Mai. “Thailand is my homeland too, we don’t feel like refugees. I won’t ever permanently go back. We’re Shan and we’re Thai, this is our culture and we’re going to keep it alive, right here.”