Guest contributor

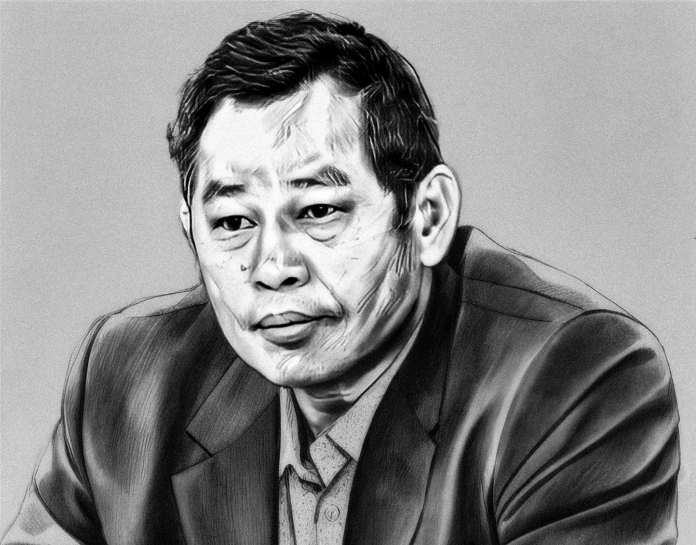

Maung Zarni

Who will protect the Rohingya in Myanmar? This is becoming an urgent question. And yet there are no easy answers.

The latest tactic by the Myanmar military is the forceful conscription of Rohingya males to fight against the ethnic Rakhine Arakan Army (AA).

The Rohingya have been caught between hostile but powerful actors inside their own ancestral region – namely the military and the AA.

Bangladesh is hosting 1.2 million Rohingya survivors of Myanmar’s different waves of genocidal expulsion.

Dhaka considers their presence a burden on the country and some perceive this population of “forcibly displaced Myanmar” as a threat to national security.

Accordingly, Bangladesh has neither accorded the Rohingya the international legal recognition as refugees nor has it provided them with any opportunities.

Nearly half of the 1.2 million Rohingya are school-aged youth languishing in open-air prisons called “refugee camps” in Cox’s Bazar, without any livelihood or educational opportunities.

A brief historical detour is in order.

Before it was annexed into the ethnic Bama kingdom at the end of 1784, Rakhine was formerly an independent coastal and cosmopolitan (multi-faith and multi-ethnic) kingdom known as Arakan which stretched well into the neighbouring East Bengal.

Rakhine is adjacent to present-day Bangladesh and central to both China and India’s mega-development projects such as deep sea-ports and transport hubs, as well as gas and oil projects.

In January 2020, I was at The Hague with Rohingya activist Nay San Lwin, co-founder of the Free Rohingya Coalition, when the sitting president of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) declared Rohingya – by their own group’s ethnic identity – were “a protected group” under the Genocide Convention in The Gambia vs. Myanmar case.

But the U.N. lacks enforcement mechanisms, unlike national courts backed by law enforcement agencies (and by extension, the armed forces), the ICJ judges can only look on helplessly when a state party breaches its obligations under international law.

Myanmar has for all intents and purposes disregarded the ICJ provisional measures to protect the remaining 600,000 Rohingya genocide survivors, along with the evidence of the crimes such as the villages burned down by the military.

What has complicated Myanmar’s genocide equation is that now the territories where the Rohingya remain have become a battlefield between the military and the AA.

On April 30, BBC Burmese aired a news story about Rohingya given basic military training and equipped with weapons by the military that has for decades carried out the genocide against them.

In the midst of the genocidal destruction of Rohingya in 2016-17, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing openly declared Rohingya in Myanmar “an unfinished business.”

The military has opted for the mobilization of 600,000 Rohingya still in Myanmar, and if the most recent BBC Burmese news report is accurate, along with Rohingya refugee youth from the camps in Bangladesh.

In the predominantly Rohingya town of Buthidaung, regime administrators instigated “anti-war protests” by Rohingya residents. The protesters carried signs targeting the AA and its placement of troops among Rohingya villages.

When the AA and its political wing, the United League of Arakan (ULA), officially rejected the Rohingya as indigenous co-residents of Arakan State, the Rohingya were forced to rethink their warming sentiments towards the AA.

Here’s my four objections:

First, the military is doing something illegal or unlawful when it recruits Rohingya because it doesn’t recognize them as Myanmar citizens, and only citizens can serve in the armed forces.

Well, there is no law as such. Not even the military is considered a lawful government. Why would it care about the legality of its deeds as far as its forced conscription of Rohingya?

Second, the Rohingya have always been native to Myanmar. It is the state that has forcibly stripped the entire population of their rightful citizenship since 1962 after former dictator General Ne Win’s views became increasingly Islamophobic.

Third, the world is now back to the future. The British East India Company used mercenaries as early as the 17th Century, and the Company used its mercenaries in the first Anglo-Burmese War during which the Bama-annexed Rakhine coastal region was snatched by the company as its possession.

Fourth, what other better options are there for the 600,000 Rohingya trapped without any protection? As a predominantly Muslim population, what are they supposed to do?

Do they stay put as unarmed civilians in their villages, wards and towns where they are sitting ducks caught in the crossfire between the military and the AA?

Should they get on rickety fishing boats, pay human trafficking gangs large sums of money and risk their lives on the Andaman Sea to escape to other countries such as Indonesia, Thailand or Malaysia?

As a matter of principle, I am absolutely against forced conscription, migration and violence.

But who I am leading a privileged life in the U.K. to pass moral judgement on Rohingya who live “in the tiger’s mouth” – as we say in Burmese – to receive military training, be equipped with AK-47s or Made-in-Myanmar rifles, and fight as auxiliaries in the genocidal military?

I will never know what choice I would make if I were in their dire situation.

These young Rohingya men live in constant and real danger of being killed in the crossfire. They have survived genocide. I can’t imagine the level of trauma, fear and concerns for their personal safety and that of their loved ones.

My vision as an exile for Myanmar is a post-national/ethnic state where all ethnic communities enjoy equality and where every person irrespective of faith, ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender enjoys basic human and political and civil rights.

There should be no distinction in group and individual rights for all inhabitants of the country where they were born.

But today Myanmar is the antithesis of my vision. Every ethnic community, irrespective of their faith, is armed. Buddhists are armed, despite Lord Buddha’s teaching for non-violence. Christians are armed despite Christ’s teaching to love thy neighbour.

Virtually all ethnic armed organizations are involved in one form of illicit trade or another. The World Bank doesn’t fund revolutions and resistance movements.

Only the Rohingya have remained unarmed. In a country where anarchy and chaos reigns supreme you are either unarmed sitting ducks waiting to be killed by others who are well-armed and hostile towards you, or you are armed and able to defend your community.

The Rohingya make their own pragmatic choices. I, for one, respect their choice.

Maung Zarni is a UK-exiled scholar and revolutionary from Burma with 35 years of direct political involvement in Burmese affairs.

DVB publishes a diversity of opinions that does not reflect DVB editorial policy. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our stories: [email protected]