“I cannot go back to Shan State because of the civil war. I came to Rangoon as there are a lot more jobs here,” says Nan Nge Bee, one of 12 apprentices learning the new skills of hospitality and food preparation in a free training programme for women from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The programme, at the Yangon Bakehouse, was developed by four women — a baker, a nutritionist, a businesswoman and a development consultant — who joined forces six years ago with the idea of setting up a business that would make a positive difference in the lives of young Burmese women.

Heatherly Bucher, a professional baker and one of the founders, recalls how she first saw an opportunity to help local women benefit from changes in Burma’s economy as the country started opening up.

“I had the idea of teaching a few women from my home kitchen the basics of European bread-making,” she explains. “In Rangoon, the supply was limited, but demand was growing.”

Later, a friend and future partner in the venture, Kelly McDonald, suggested opening a cafe built on the social-business model, in which a company aims to use its profits to benefit its employees and the wider community. Teaming up with two other women, Phyu Phyu Thin and Cavelle Dove, they began to scout for locations.

The first cafe was opened in Rangoon’s Botahtaung Township. Now the business has grown to two cafes and a catering and delivery service.

A business with a mission

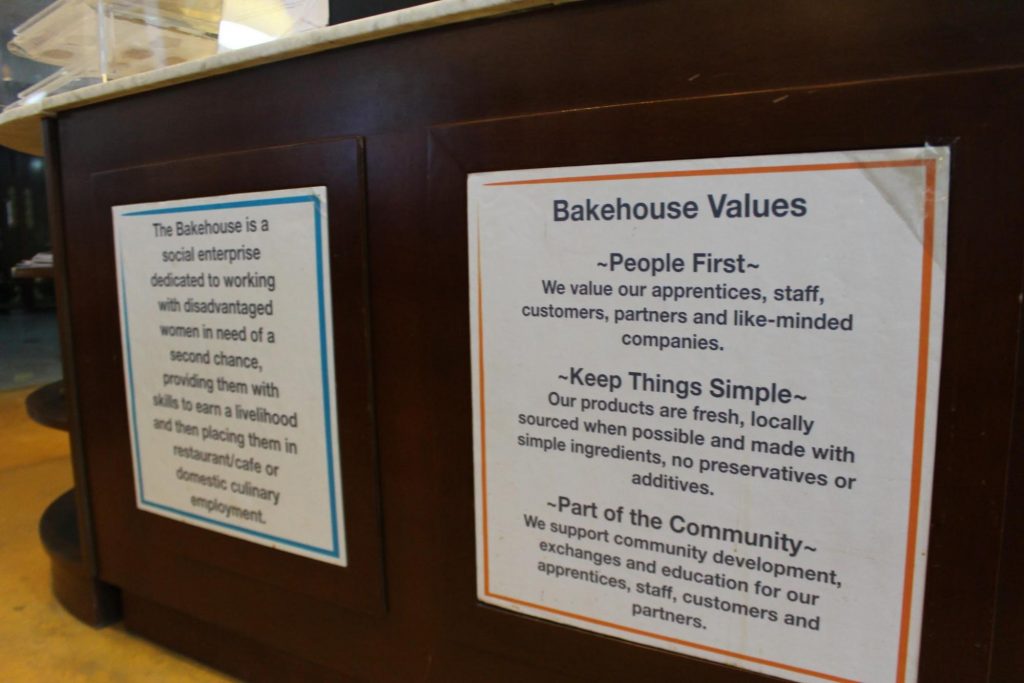

Taped to the cashier counter, under a row of chocolate-chip cookies and baked goods, is their mission statement, which declares their dedication to “disadvantaged women in need of a second chance, providing them with skills to earn a livelihood and then placing them in a restaurant/cafe or domestic culinary employment.”

The trainees come from all over Burma and have very diverse backgrounds. “Some never had the opportunity to complete secondary school. Some found themselves in dishonouring, destructive work. Others were imprisoned unjustly under the former regime,” says Bucher.

In a country where there is only five years of compulsory education and, according to UNESCO, only 50 percent of children are enrolled in secondary education (with the rates for girls considerably lower than for boys), women are often exploited for cheap labour and sometimes forced to enter the sex trade to survive. Despite their many differences, the one thing all of the trainees have in common, according to Bucher, is that previously “they didn’t have enough skills to earn a sustainable wage in an honourable way.”

A lot of women apply to become trainees, but funding constraints limit the number who can be accepted to just 12 women per class. In the 10-month programme, two classes of trainees learn English from volunteer Angus Johnstone and front-of-house skills and food preparation from Australian chef Dean Parrish.

The programme is a steep learning curve for the women, as many have never spoken a word of English before joining. However, the majority of participants manage to complete the course, with only one or two dropping out of each class.

The social-business model was chosen by the founders because they wanted a business structure that meets a social need but which could be sustainable and not dependent on grants. It’s a new business model that is slowly growing in Rangoon as more start-ups flock to Burma’s biggest city. “Even for-profit companies without any particular social values at heart are encouraged through customer interaction and purchasing power to consider being better citizens,” says Bucher.

However, starting a social business in Rangoon is no easy task. The city’s high rents, aging infrastructure and unreliable electricity supply make the city a challenging place to work. In addition, social business takes on additional burdens of transparency, funding terms and legal registration. Burma’s business laws are also constantly shifting, which does not encourage capital funding options.

Only a handful of social businesses like Yangon Bakehouse exist in Burma. However, companies like ProjectHub Yangon, SustainableMyanmar and SPA are now providing incubator workshops and entrepreneurship programmes, encouraging the people of Burma to launch their own businesses.

A focus on women

Allison Silvester, the co-founder of Project Hub Yangon, points out that social businesses are not yet recognised within Burma’s regulatory environment, and so aren’t subject to special tax breaks, while registration costs remain high.

“The business environment in Myanmar [Burma] is exceptionally challenging for young businesses,” says Silvester. After meeting talented women interested in starting businesses, in 2014 she co-founded Project W, an incubation programme that focused on women.

“We thought if we focused solely on a women’s cohort, it would help us bring women out of the woodwork,” says Silvester. She says two women successfully established and are now growing their businesses after completing the course. One is 28-year-old Cing Zeel Niang from Chin State, who went on to successfully set up her own business selling Chin textiles online via Facebook.

Empowering women with technical and life skills should be done by every business, says Silvester, whether they be social, private or non-profit.

Escaping the heat and traffic in Rangoon, many locals and tourists take refuge at Yangon Bakehouse at Pearl Condo, enjoying some homemade favourites like cinnamon buns and sourdough bread.

Trainee Nan Nge Bee prepares a baguette while discussing her training and ambitions after she completes her course.

“I like the bakery, that is my favourite part of work,” she says shyly, adding that she hopes to work in a similar style bakery in the future, or even set up her own business someday.

[related]

She’s assisted by Myo Min Tun, the manager of the cafe’s bakery, who applied for a job after hearing about the social-business model at Yangon Bakehouse.

“I worked in another hotel but when the Yangon Bakehouse opened up, I wanted to work here as this is a social business. It’s not only a business, but we support a lot of women,” he says.

Boucher says despite all the challenges, it has been rewarding to see women choose their own path of employment after completing their apprenticeship. Some become small-business owners, or return to rural areas to become a part of a cooperative, while others go on to do something that many women in Burma never have a chance to do: complete their formal education.