“Can I get pregnant from sitting on a toilet seat?” asks one concerned young girl to a hotline counsellor in Rangoon. “A man used the public toilet before me and there was urine on the seat and I sat on it…”

Women in Burma are so worried about getting pregnant out of wedlock that 22-year-old youth counsellor Khin Su Yi receives many such phone calls every day.

The stigma is so great that if an unmarried woman becomes pregnant, “some women may be forced into marriage or will desperately seek out an illegal abortion that may be unsafe,” says Naw Kyuju Ni, sexual violence coordinator at faith-based organisation Tearfund.

The blame for unwanted pregnancies invariably falls on the woman, not the man. In some cases, the parents of the couple will force the couple to marry; in others, the woman will be thrown out of the family home. If that happens, she may be unable to continue her studies or find a job, and finding a future marriage partner becomes all but impossible, explains Khin Su Yi.

Abortion is also illegal, so a woman’s options are limited if she wants to terminate the pregnancy. Dr. Sid Naing, the country director of Marie Stopes International (MSI), a non-governmental organisation that provides contraception and safe abortion services in 38 countries, explains that this often leads to some dangerous decisions.

“Because medical interventions are not legal in such cases, women will usually have access to advice or interventions from unqualified and unskilled people in the community, which can lead to serious life and health consequences for them,” he says.

Despite all these risks, however, talking about contraception remains a major taboo in Burma. Sex education is nonexistent in schools, and parents shy away from talking about ways to prevent pregnancy because doing so is seen as encouraging promiscuous behaviour.

One lifeline for teens wanting information is a free counselling hotline service operated by the Myanmar Medical Youth Association, which has one phone number for boys and another for girls.

Counsellors for both boys and girls say there is no doubt young people are having sex before marriage — but what is worrying is they don’t have a basic understanding of available contraceptives.

Condoms and the pill: the big taboo

Khin Su Yi can’t recall receiving even a single request for information about condoms from a girl — not because they already know everything they need to know about them, but because it is culturally off-limits to discuss something that is considered to be the man’s choice. “They never even say the word aloud because they are shy,” says Khin Su Yi.

“Because of our male-dominated culture, men will choose if they use condoms or not. So girls don’t even ask, because if they said ‘use condoms’ to their boyfriends they are worried the boyfriend will think they have had previous experience,” she adds.

Pyae Sone, a 29-year-old counsellor, agrees that boys don’t want to use condoms. Surprisingly, he says a new trend is boys wanting to know about a woman’s menstruation cycle, so they can use the calendar method.

Another new trend is couples choosing to use the emergency contraceptive pill — the so-called “morning-after pill” — on a regular basis. “It only costs 500 or 1,000 kyat,” says Khin Su Yi, explaining the appeal of this approach.

The problem is that they don’t know about the possible side effects of frequently using the pill, and often don’t understand the importance of timing, which can affect how well it works. As the name implies, the pill should only be used for emergencies, says Dr. Sid Naing. “If a woman is known to be exposed to the risk of getting pregnant every week or so, it is no longer an emergency and she should then be on a more regular and safer contraceptive.”

UNFPA, Ministry of Health and Marie Stopes International under a new US$1 million program. (Photo: Libby Hogan / DVB)

While it seems to be men who get the final say on what contraception they use, it’s a woman’s fault if she becomes pregnant.

Dr. May Thit Lwin, who works at an MSI clinic in Thanlyin Township in Rangoon, says that from her own experience, younger women prefer the three-month Depo Provera injection to monthly pills. “Even if the injection is painful, they like this method as many say they forget to take the monthly pill every day.” As for older women, she says they mostly prefer the long-term Jadelle arm implant method, which prevents pregnancy for up to five years.

This clinic is receiving support from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and is operated by MSI under a new programme that is rolling out US$1 million worth of implant contraceptives — part of a $2.6-million supply of reproductive health-related products that is being made available.

This is a first for many women in Burma — to be offered the arm implant and the small-coil intrauterine device (IUD) free of charge for low-income families. Both are reversible implant contraceptives. Ma Ni Ni Khin, a 38-year-old mother of three, says she is very happy to receive her implant, although at first her husband was worried there might be side-effects or that the method was irreversible and would affect her health.

“It is easier for older women to discuss, they don’t have to persuade their husbands, parents or parents-in-law like younger women do,” she says, adding: “I only got information about different contraceptives after I got married — nothing during my school years.”

However, dealing with cultural sensitivities and taboos remains a challenge.

Dr. May Thit Lwin says the arm implant is more popular that the IUD. “Women are still afraid to feel the string [attached to the IUD] inside their vagina and scared to insert their finger inside their vagina,” she explains. Most of her clients have never used tampons during menstruation and believe the vagina should never be seen or touched by a woman herself.

Lack of information and unwanted pregnancy

“Girls have a right to complete their education,” says Janet E. Jackson, the UNFPA representative for Burma, explaining why it is so important to improve access to information about birth control.

But the loss of educational opportunities is not the worst thing that can happen to a young woman who has an unplanned pregnancy. According to data from Burma’s most recent census, girls and women between the ages of 15 and 24 accounted for 24 percent of all maternal mortality incidents reported in 2013.

“The biggest challenge is access and presenting comprehensive of information and services to young people,” says Jackson, emphasising the need for more information and more affordable access to contraceptives to prevent unwanted pregnancies and tackle the high mortality rate among young mothers.

But it’s not just about disseminating more information — it also has to be the right information.

Pyae Sone, the counsellor, says teens today are “facing information overload.” As Burma opens up, advertising increasingly bombards its young people — which might explain why Pyae Sone says more and more boys are asking him about drugs for longer-lasting sex, or whether having sex for a long time increases the risk of contracting HIV or other sexually-transmitted diseases.

“Although the questions I receive are very diverse, they all come down to the root cause of a very low understanding of basic facts, like HIV transmission,” he says.

Counsellor Khin Su Yi agrees, noting that she has often had to explain how the fertilisation process of an egg works when answering phone calls.

Because there are so many misconceptions about contraception shared between friends, trying to replace fiction with the facts is a major challenge. “It’s very difficult for us as counsellors to replace their misinformation as they have heard it from friends, who are often not trustworthy sources of information,” says Pyae Sone.

Future hopes

Providing the right information from the start of adolescence is another mission UNFPA and the Ministry of Health and Sports (MHS) are trying to implement. As reproductive health lessons are not taught in schools, UNFPA and MHS are supporting 70 health centres across the country to include a youth corner where they can have a quiet space to access information about contraceptives, among other topics .

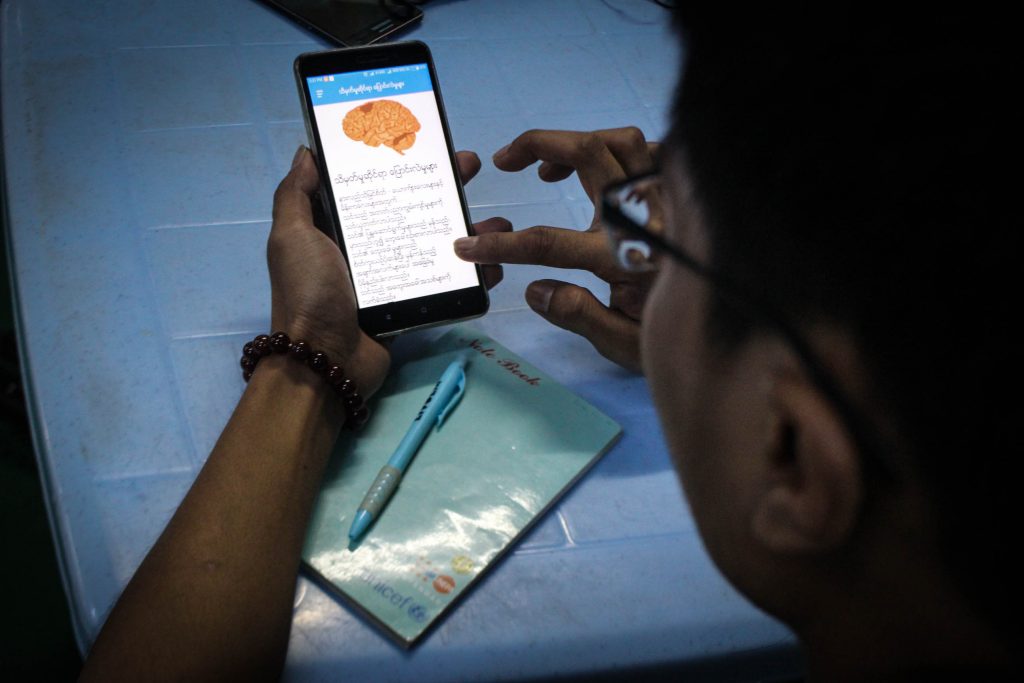

A new sexual health app has also been launched which provides information on topics such as safe sex with contraceptives, early marriage and unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections and HIV. “The launch of the app is exciting as it presents access to reliable data and trusted information that doesn’t push any choices but lets teenagers look up information privately when they choose,” says Jackson.

Khin Su Yi believes that age-appropriate body and reproductive health information should be compulsory at schools.

“Although the younger generation is eager to know information about sexual matters, the older generation, like parents and teachers, are still considering whether to talk about this information, whether it is shameful or taboo,” she says.

But 32-year-old Ma Saw Pyae Pyae Khine, who recently chose the implant methods, sees no shame in teaching children about their bodies. “I hope my children get this teaching at a younger age than I did and at a school level like in other countries,” she says.