By May Soe for Reporting Asean

It’s 9 a.m. – before classes start – and children’s shouts and squeals of laughter fill the air of a school compound in a hilly area not far from the center of Mae Sot, a Thai city on the border with Myanmar.

The school is like many others, but also different. It is among the more than 65 schools in Tak Province that many children of exiles and others who fled Myanmar after the 2021 military coup go to.

While these have catered mainly to the children of migrant workers and people from Myanmar who had sought refuge in Thailand in decades past, student numbers have spiked in the continuing exodus of people from Myanmar.

“I wasn’t happy when I just arrived, but felt happy after I started attending school,” said 11-year-old Toe Toe, who is in grade four. “Now I can’t decide whether I want to go back or live here, because there is still some crisis in Myanmar. But I miss my relatives and friends sometimes.”

“I didn’t have any income. So I sent my children to migrant school, like other displaced persons,” said a mother who arrived with her teenage daughter and 11-year-old son. After finding a suitable school for her son, who was struggling with being away from home, she added: “Now he’s happy, and I’m also relieved.”

Seeing their children get some education is a huge relief for many parents. Schools also provide social support, keeping young people busy in six-hour class days and allowing normal interaction in the local community.

One mother recalled how her son fretted about returning to Myanmar after they were stopped by Thai police while out buying food. “So I sent my son to school just for him to be happy. I wanted him not to feel insecure. I asked him to go play in school,” she said.

At the same time, a mother in her late 30s, living here since the end of 2021, worries about her son’s future if and when their application for refugee resettlement is approved. “My son has to learn the subjects in Burmese and I’m afraid that he can’t catch up,” she said.

Some schools in Mae Sot provide elementary classes while others offer more levels, from kindergarten to high school, and take in students from age three to 18-years-old. Burmese is the language of instruction. Some schools have language classes in Thai and Karen, the ethnic language used by many here.

Some Myanmar teachers have been in Thailand for years, and some are teachers who joined the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) soon after the military coup. Others are foreign volunteers.

Schools follow Myanmar’s education curriculum for kindergarten to primary students up to grade 8. For grades 9 to 12, the schools use the General Educational Development (GED) programme, whose completion equips students with high school qualifications they can use to apply for university.

Some schools collect fees, while others do not. Parents pay from 300 to 2,000 Thai baht ($8.8 to 59 USD) per month for each student, apart from the one-time admission fee.

International schools take in Thai and foreign students, but the fee of around 6,000 Thai baht ($176 USD) per month is too expensive for many Myanmar families.

Before the 2021 coup, there were 65 migrant schools and some 13,000 Myanmar students in Tak Province, said *Daw May (not her real name), a senior manager at a school for migrant students. Most students are from Karen families who arrived a decade or more ago, but others are Kachin, Karenni, Mon and Bamar. Myanmar parents talk of a handful of schools, perhaps two or three, that have opened since 2021.

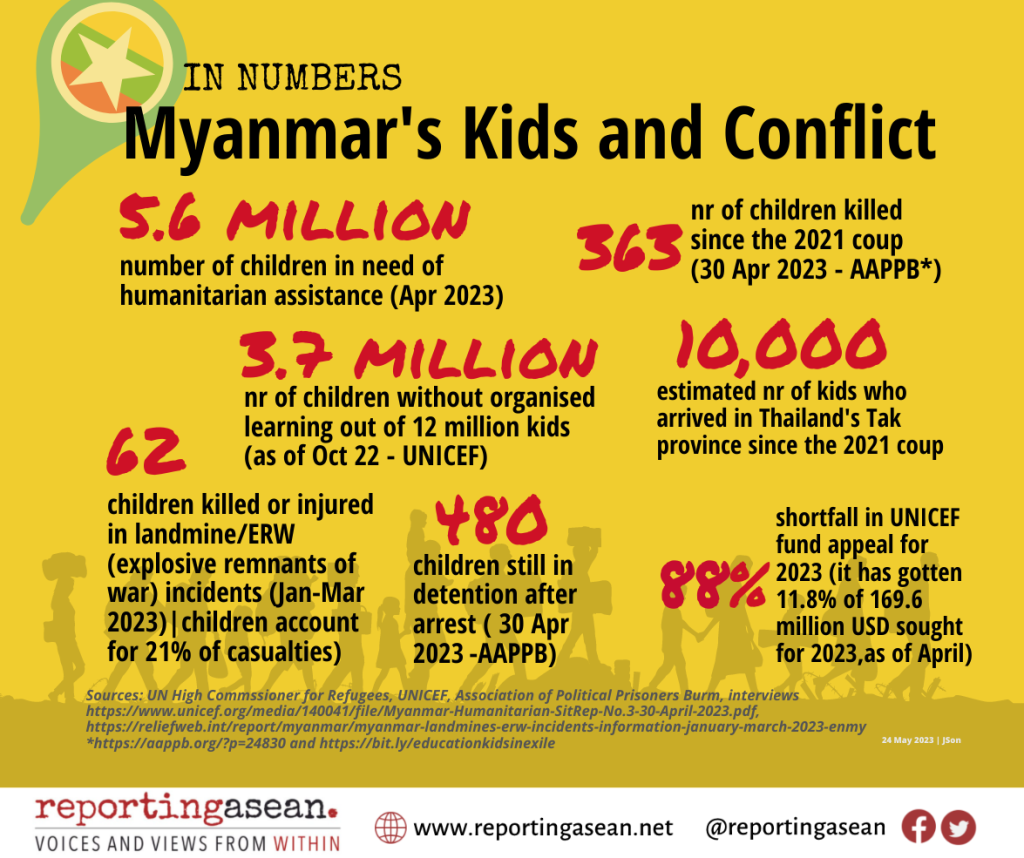

There is a long queue of children waiting to register for the 2023-2024 school year, which started June 1. More than 10,000 school-aged children and students have arrived in town since the February 2021 coup, estimated Daw May.

“About 5,000 students won’t be sure to get registration for the coming school year because every school in Mae Sot is full,” she said.

Her school – which takes in up to high school students – had 30% more students than it usually has, in the last (2022-23) term. It had more than 1,000 students, compared to the usual 700 or so. It can no longer accept new enrollments in the coming term. (Most schools have 100 to 500 students.)

Humanitarian funding helps keep the schools going, but education managers said that educational resources have fallen by 50 to 70 percent since the end of the last school term. “We face the need for infrastructure, learning materials, teaching honoraria and fees. We also have headaches about the cost of gasoline for school buses in the coming year,” added Daw May.

While education has been disrupted by Myanmar’s conflicts through the decades, the disruption after the 2021 military coup has been much more widespread – given the political, economic and humanitarian crises along with armed conflict and anti-military resistance across the country.

These come on top of the limited access to learning since school closures once the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020.

As of October 2022, at least 3.7 million young people out of the total 12 million learners prior to the school shutdown during the pandemic, “have not had access to organized learning for two years – initially due to COVID 19-related measures and now due to the current crisis,” said Frehiwot Yilma, the UNICEF Myanmar communications specialist, in an email interview.

The military reopened schools for in-person classes in June 2022. But there is a far from conducive environment for learning in Myanmar, where most regions are now affected by conflict, including in the Karenni, Karen, Chin, Kachin, Shan, Sagaing and Magway regions.

In its April update, UNICEF Myanmar stated that due to the continued rise in the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs), including children, in north-western Sagaing: ”This disrupts children’s opportunities to learn safely.” (As of 15 May, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees states there are 763,100 IDPs in Sagaing. A total of 1.5 million remain displaced since the coup)

A total of 5.5 million children need humanitarian assistance, UNICEF Myanmar stated. Still, some communities are bent on keeping avenues for learning open.

“Children in our region already had poor opportunities before. If we can’t give them some access to education, this [situation] will get worse,” said a volunteer teacher in Karenni State. “The main challenge is security, and the second is not having enough food.”

“Although we face difficulties and dangerous situations, we have to send our children to school,” said a father in Sagaing Region.

“The current political situation is blocking the future of children’s education,” said Daw May. “Some teenagers in the border areas are only interested in earning money for survival, and some have joined ethnic armed groups.”