Originally published on Mohinga Matters

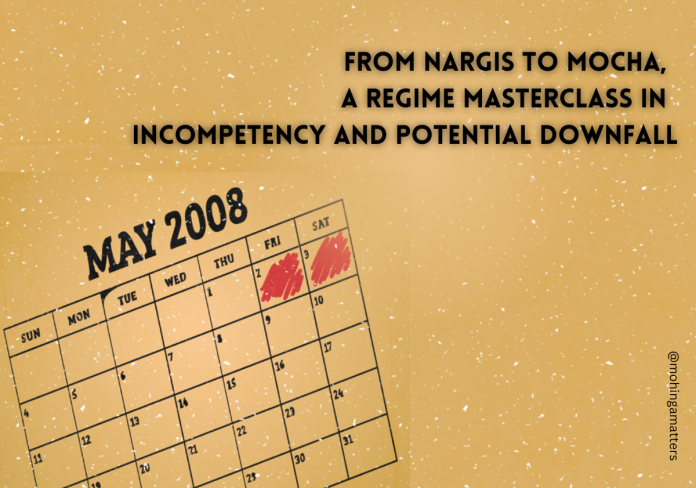

As the survivors of Cyclone Mocha cling to receive aid and resettlement in Sittwe and other affected areas, many recall what happened 15 years ago in the Ayeyarwaddy Region. Cyclone Nargis, which took place on May 2, 2008, is regarded as the most devastating natural disaster that ever took place in Myanmar. Although both Mocha and Nargis were said to be Category 4 storms, the latter’s impact was much more severe in terms of destruction. Despite its massive fury that resulted in significant death tolls, Nargis is remembered to this day for the then-military regime’s mismanagement.

The regime’s delayed response and underlying factors

Nargis affected more than 50 townships, mainly in Ayeyarwaddy and Yangon regions. With wind speeds of up to 200 km per hour accompanied by 3.6-meter-high waves, the cyclone caused the greatest damage in the Ayeyarwady Region. More than 140,000 people lost their lives and 800,000 were displaced. Thousands of families were broken up and it took the region nearly a decade to get back on its feet.

Although numerous international weather forecasts highlighted the potential cyclone heading towards the delta area of Myanmar in the last days of April 2008, both the military government and the public paid little attention. The regime, which was then led by Senior General Than Shwe, did not even issue proper warnings, let alone relocate people. There were rumors that the regime deliberately withheld alarming information to avoid causing panic. Also, people in the delta area were not accustomed to encountering storms of such magnitude, leading them to dismiss the weather news lightly. As a result, the combination of the regime’s misrule and the people’s ignorance contributed to the high death tolls.

When the catastrophe eventually struck, the regime not only delayed its own evacuation activities but also took a week to let in the first international aid due to “security concerns”. The military officials’ logic was that seeking outside assistance would raise a major question of their capability to govern. Consequently, when international aid was finally allowed, it came with many conditions. The aircraft had to take off immediately after dropping off supplies and only their soldiers were permitted to handle the distribution in the areas, etc.

Another factor that made the junta hesitant in accepting international help was the fear that the outsiders would witness not only the cyclone’s impact but also the internal state of the country, potentially risking an intervention. Although the chances were slim, speculations were not completely far off. It was reported that the US warships were on standby in the Andaman Sea, not far off the coast of Myanmar, to assist the relief effort. It was believed by many Myanmar people at that time that the US Marines were ready to barge into the country to evacuate the cyclone survivors and topple the military government while they were at it. At the same time, France’s then foreign minister, Bernard Kouchner attempted to convince the UN Security Council to adopt the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) Act and deliver aid to Myanmar by force. In the same week, Time magazine published an article titled “Is It Time to Invade Burma?”, expressing the international community’s frustration in being unable to help the people of Myanmar.

In short, the regime prioritized its own safety and image over the survival chances of its citizens..

The infamous referendum

In the same week when nearly millions of people were affected by a natural disaster, the regime had another agenda. After the generals arrested the members of the National League for Democracy (NLD) by calling their election victory in 1990 null and void, they spent fourteen years drafting a constitution that would later be known as the 2008 Constitution. The referendum to approve said constitution happened to be scheduled on May 10, 2008. Hence, instead of attending to the country’s greatest disaster, the generals were too busy staging an election that would guarantee the military a firm place in Myanmar’s politics with a constitution that reserves 25% of the parliamentarian seats for military representatives. Although it was widely recognized that the entire process was rigged and nobody in the country took it seriously, the generals ensured that the referendum took place as scheduled and received sufficient international media coverage. Some ironically said that at least it was nice of the generals to postpone the referendum in the disaster-stricken areas for two weeks. A man in his 70s from Bogale Town, where the epicenter of the cyclone took place, recalled the moment. “As I sat looking out of the empty land where my house used to be, hoping for food supplies, the military’s men came and told me to come vote for the referendum. I told them they were free to cast on my behalf as I had other priorities”.

In the end, the regime achieved what it wanted: more than 90% of the alleged approval of the constitution that had been developed by 702 handpicked delegates chosen by the generals.

Than Shwe, the man behind the curtain

There was a rumor that the daughter of the Senior General made a callous remark “Fishes will feast on the dead bodies, why bother cleaning up” when Than Shwe’s management was questioned over piles of bodies being stuck in the rivers of disaster-affected areas. As if he had been listening to his daughter, Than Shwe and his men never managed or planned to dispose of thousands of bodies. All that was seen from the military in the aftermath was chopping down trees that fell on the streets of Yangon and acting as middlemen for the distribution of relief goods from the outside. And even while doing just that, the regime managed to add to the people’s suffering. Several individuals including the popular Myanmar comedian Zaganar were arrested for engaging in relief activities and talking to the international media without consulting the authorities. Moreover, fortified biscuits and other supplies handed over to the regime for redistribution ended up being sold on the black market.

Even when his daughter voiced her lack of sensitivity in this crisis, the regime leader himself remained largely silent throughout. He was pictured greeting refugees in a few camps in nothing less than propaganda images. Other than that, Than Shwe did not step out of his comfort zone, refusing to lead the evacuation efforts. In the meantime, he masterminded the referendum, held the general election in 2010, and orchestrated a transfer of power among his most loyal followers: Thein Sein (then President), Min Aung Hlaing (the current commander-in-chief of the military) and Thura Shwe Mann (then speaker of parliament and an outcast now). Since then, Than Shwe has stayed behind the scenes and distanced himself from active politics. By doing that, he must have believed he managed to deceive the world into forgetting his role in ordering massacres and acts of violence throughout his two-decade reign as a military leader.

However, little did he know that at the very least people still remember him as the man responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands during the Nargis cyclone. And the time is near when he will face the consequences for his crimes, above and beyond.

History repeating itself?

Than Shwe’s plan to ease out his escape came to an end with Min Aung Hlaing’s coup in February 2021. The 90-year-old former ruler’s name resurfaced in the political scene since the early days of the coup. People speculated whether Than Shwe once again orchestrated the coup or his most loyal follower did the unthinkable without consulting the master. Regardless, whatever Than Shwe may have gotten away with the transition of power to “civilian government” twelve years ago has now been undone. Through the Spring Revolution, the people have vowed to eradicate the military institution entirely from the political landscape, and hold every military general, past and present, accountable for their crimes. Than Shwe’s most cherished 2008 Constitution has been torn apart.

As a clever, cunning, and experienced dictator, Than Shwe must have sensed the danger. Once again, he appeared again in the country’s political news when China’s foreign minister Qin Gang visited him in Naypyidaw in early May 2023. Qin Gang was the highest-ranking Chinese official to set foot in Myanmar since the coup, and he ensured that he paid a visit to the old military leader. According to reports, Than Shwe expressed gratitude to Beijing for its “strong assistance to Myanmar’s economic and social development” while Qin also commended Than Shwe’s “important contribution to the development of China-Myanmar relations”. Whatever Than Shwe may have in his mind about the coup, he seems determined to safeguard his remaining years and his family’s fortune from what’s to come.

Coincidentally, just as Than Shwe reappeared in the scene, another deadly cyclone struck Myanmar. And once again, the military regime has failed to take adequate action. While the number of casualties may be lower compared to Nargis, the losses are still significant, particularly in Sittwe City of Rakhine State and Rohingya camps. Hundreds of people died and some 400,000 were affected. Furthermore, Min Aung Hlaing’s council delayed the immediate entry of international aid. Essentially, we are witnessing similar actions by another generation of the regime’s generals in the aftermath of Cyclone Mocha.

Irrational wishful thinkings

Despite enduring oppression and suffering under successive military regimes, the people of Myanmar have always believed that better days are ahead. Each (ir)regular environmental event instills a ray of hope among the people. Be it an earthquake, a storm, or even a lunar eclipse, they are signs of imminent political change that will bring freedom and prosperity to the country. In the past, people relied on such wishful thinking to keep going, convincing themselves that things would eventually improve.

Today, the former and current dictators, who have failed to deal with two powerful cyclones on top of numerous crimes they have committed individually and together, seem to be back in the engine room, struggling to navigate the ship they have steered so low. Just the idea of US Navy vessels being positioned near Myanmar’s coast fifteen years ago was enough to make the generals paranoid. With the Spring Revolution gaining momentum, one can only wonder how they must be feeling now. Equipped with viable means, the people of Myanmar may not have to rely on a natural disaster to help topple the regime someday soon.

References

- Learning from Cyclone Nargis, United Nations Environment Programme, June 2009

- No Bad News for the King, Emma Larkin, 2011

- 10 years after, Cyclone Nargis still holds lessons for Myanmar, Gregory Gottlieb, May 2018

- China’s foreign minister touts ‘friendship’ on Myanmar visit, Aljazeera, May 2023

Mohinga Matters is a platform where aspiring writers share their thoughts, ideas and opinions freely.