LU KYAW FOR REPORTING ASEAN

10 DECEMBER 2022

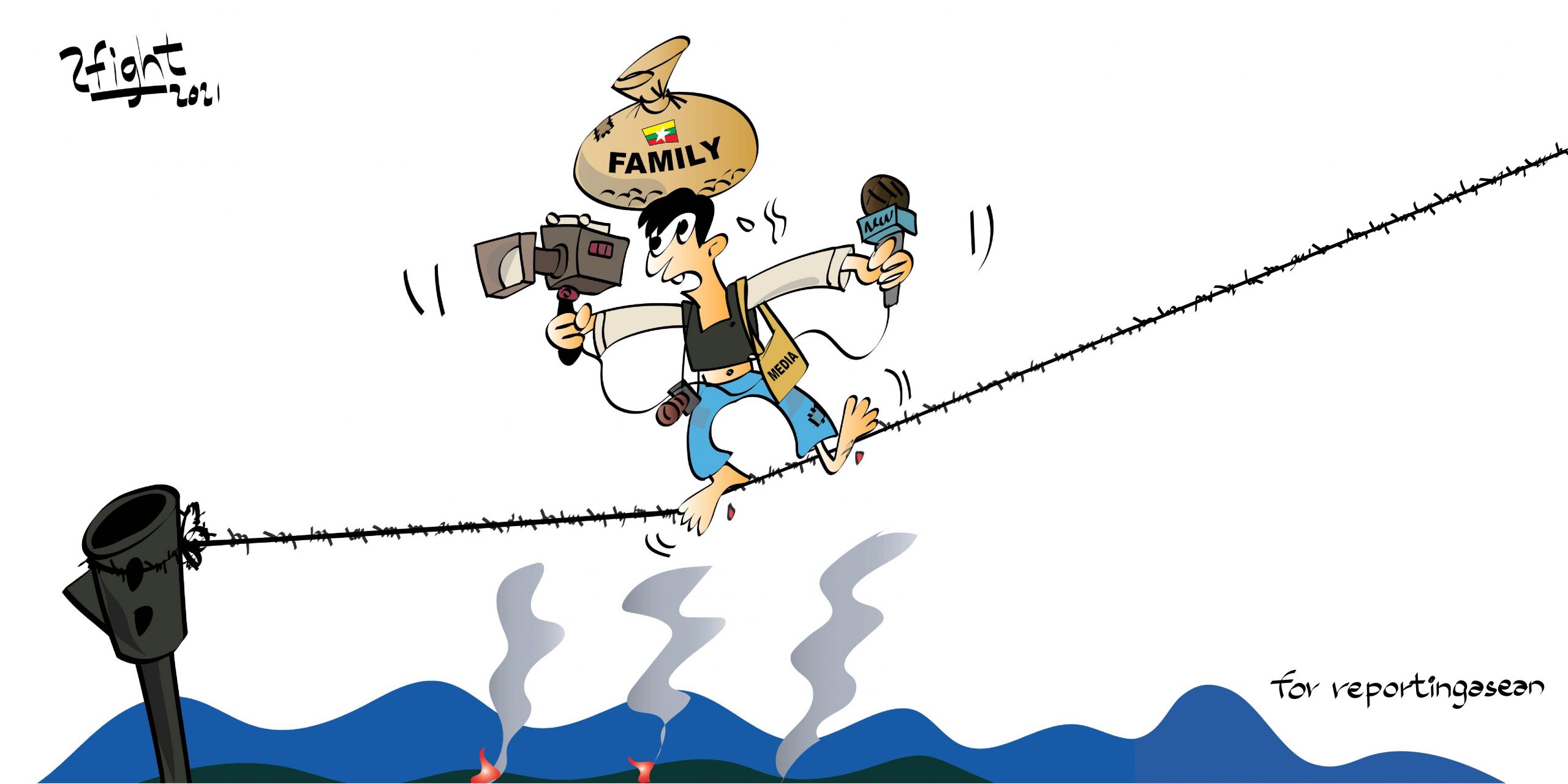

“The saying ‘journalism is not a crime’ does not work here. It’s the opposite. We (journalists) are afraid of everything. We have to worry about everything,” says Ma Khine, who has been in working in news for eight years now.

“We can do nothing (freely). Nothing. Can’t pull out the camera, can’t take photos in public areas,” she adds, given that Myanmar’s military regime continues to arrest and prosecute journalists and shut down independent news outfits.

“I dare not let people know that I am a journalist,” Ma Khine explains, not least because of the distrust that characterises the country’s political atmosphere since the military coup of February 2021.

The risks that come with being a journalist in Myanmar have been reported widely, but individuals like Ma Khine live with these daily.

She continues to do news work inside the country, including in areas controlled by the military, despite the extremely risky news environment and inadequate income that journalism brings at a time of economic crisis.

But while she continues reporting from Yangon, the country’s commercial capital, she worries about her security.

“I haven’t been able to sleep well since the coup. I am afraid even of the clump-clump (the thud of footsteps) on the ladder (outside) my apartment. All through the day and night, I can’t feel at ease,” Ma Khine said. “If someone looks at me (for a bit longer than usual), I don’t feel secure.”

She has gotten used to moving homes again and again, keeping her news work to herself.

She has also witnessed the arrest of some of her journalist friends and has, on several occasions, fled protest sites to avoid being taken in, or shot at, by the junta’s security troops. “(It’s) not only some of my friends (who have been arrested). Other journalists who I know have been arrested by the military right in front of my eyes,” she recalled.

“When I was reporting about a demonstration against the military, soldiers fired on people and I ran and hid in a house together with the other guys. At that time, one of the policemen fired a random shot toward our hiding place and it hit the guy next to me,” she said. “I was so scared.”

Going by the count of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma), 163 media persons have been arrested since the coup, and 30 held in prison, as of 8 December 2022.

Myanmar’s military regime, or the State Administration Council (SAC), has also revoked the licenses of 14 news outlets.

Myanmar ranked 176th out of 180 countries in the 2022 World Press Freedom Index of the France-based Reporters Without Borders.

At end-December 2021, the prison census of the US-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) found the country to be the world’s second-worst jailer of journalists after China. Myanmar ranked eighth in the CPJ’s 2022 Global Impunity Index, which lists countries that have consistently failed to solve journalists’ murders.

Since the coup, many among Myanmar’s journalists have relocated to safer parts of the country, such as those held by ethnic armed organisations that have been fighting the military for decades. Many have gone into exile into neighbouring Thailand, or to other countries.

After the coup, Ma Khine’s parents, who are business people and have been managing to make ends meet, had asked her to return to their hometown. But “most of them (people in my hometown) know each other,” she explained. “I can’t continue to be a journalist there (for security reasons). I want to continue as a journalist, so I decided not to go back.”

“I can’t buy the kind of rice I ate before because prices have soared. I have to choose the cheapest for everything.”

She contributes news and features for free to news outlets that have limited editorial budgets. When media groups are able to pay her modest amounts, she sends some funds from these payments to assist detained journalists.

Many of Ma Khine’s stories are about anti-coup protests, crackdowns on protesters, the plight of political prisoners, and those killed, arrested or tortured under the military regime. At times, she also passes on information to journalists in exile.

As it is not possible to survive solely on income from news, Ma Khine makes some income from selling food that she cooks, or sourcing various items from other parts of the country for customers. “Those kinds of jobs are not my profession. But I have to work in all of them to live in Yangon and continue as journalist,” she said.

Before the coup, she was making 400,000 Myanmar kyat (around 300 US dollars in early 2021) a month, an amount that she found enough for her basic needs. These days, her income is down by half, or 200,000 kyat (less than 70 dollars at current exchange rates) in a month.

The country’s economy has been in deep crisis since the coup, which also took place during COVID-19. As of September 2022, the World Food Programme says 15.2 million people in the country of over 55 million are facing “acute food insecurity”.

The cost of a basic food basket has increased by 62% year-on-year as of its September update, the WFP said. The price of cooking oil has jumped by 137 percent, rice by 53 percent and fuel prices by 94 percent from last year, it added.

No longer able to rent a flat as she did in the past, Ma Khine stays in a tiny room she rents for 40,000 kyat (15 dollars) each month.

Like many others, she has switched to buying cheaper food options. She no longer has regular breakfasts, as well as tea times. But if there are leftovers from the previous day, she has those in the morning.

“I am eating Sin Thwe, Ze Yar,” Ma Khine said, listing the cheap broken rice she uses these days. “I had never eaten those before. I can’t buy the kind of rice I ate before because prices have soared. I used sunflower oil to cook before, (but) I don’t know what kind of oil I use now. I have to choose the cheapest for everything.”

Journalists inside the country can find themselves safer if they take up work with local media houses that have been following the SAC’s rules for reporting news.

“I can get regular income from these,” she agreed. “But if I join them, I have to avoid (reporting on) the cases which need to be covered nowadays, and I would have to report other unimportant issues (instead). So, I don’t join them.”

“I will be a journalist till the end. It doesn’t matter they arrest or kill me,” Ma Khine said. “Even if I can’t report the news, I am happy to let people know the (on-the) ground situation of Myanmar through exiled journalists.”

(END/Reporting ASEAN/Edited by J Son)