Another school hit by airstrikes in Sagaing Region

At least two residents were killed and seven others were injured by three airstrikes and attacks on Henna village in Indaw Township of Sagaing Region on Monday, the People’s Defence Force (PDF) told DVB. Indaw, which is located 209 miles (336 km) north of the Sagaing Region capital Monywa, was seized by PDF-led resistance forces on April 7.

“The two jet fighters targeted the village school,” a PDF member in Indaw told DVB. The death toll from airstrikes on a school operated by the National Unity Government (NUG) in Depayin Township on Monday has risen to 24, according to the PDF in Depayin, which is located 40-163 miles (64-262 km) north of Monywa and south of Indaw.

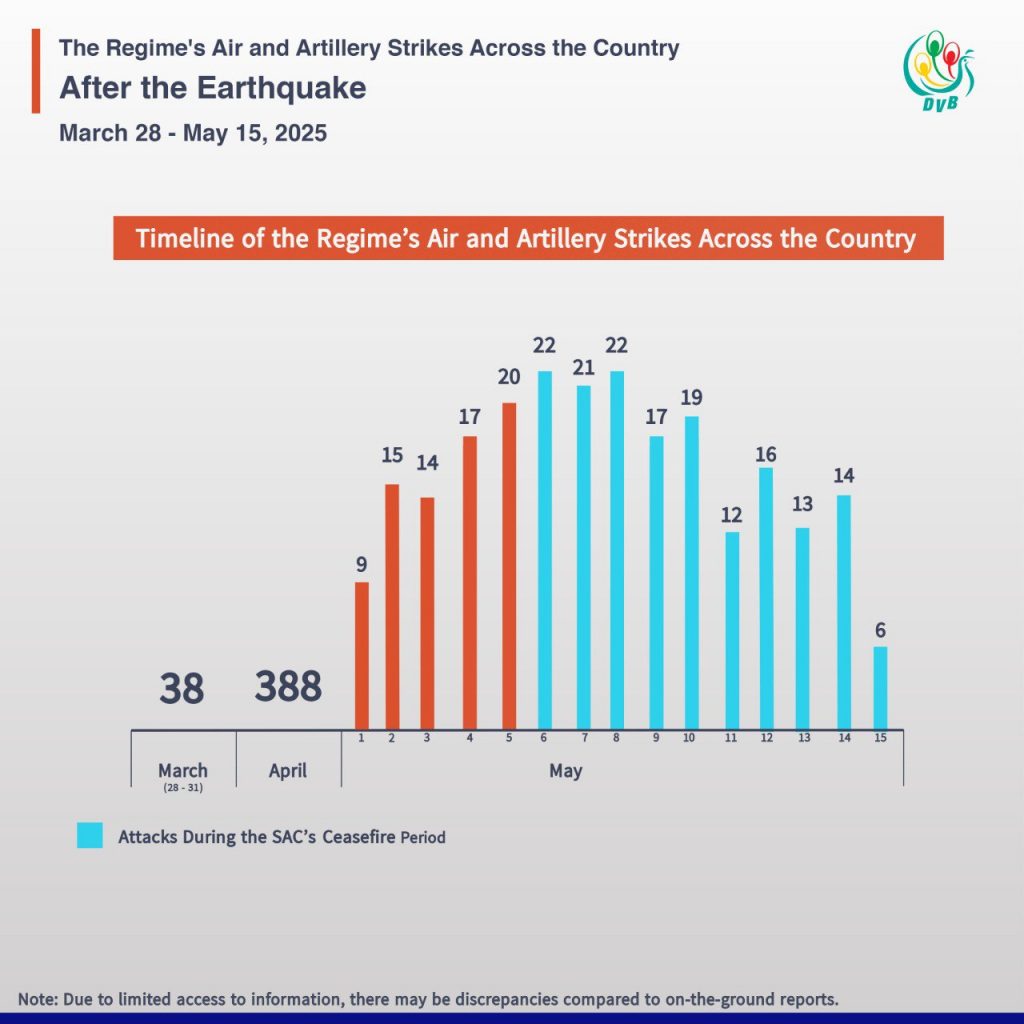

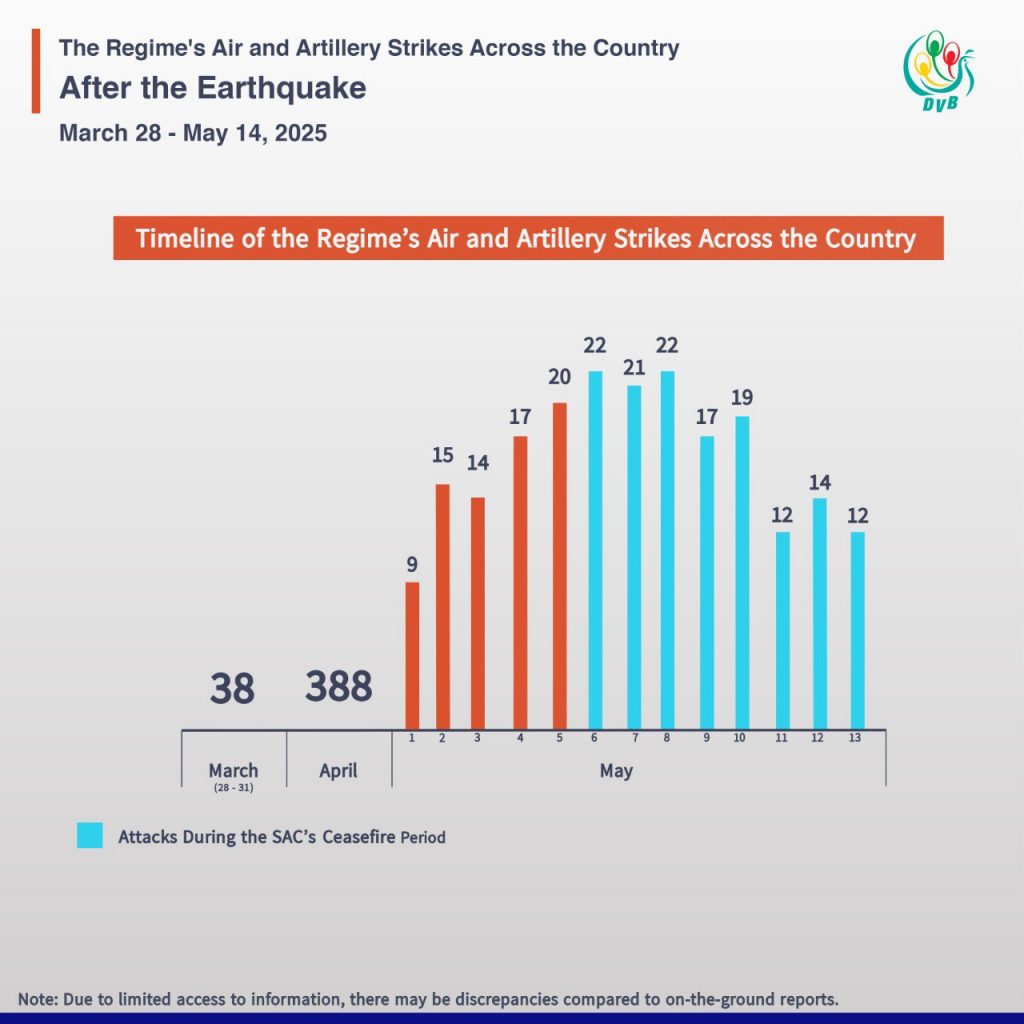

The NUG has documented that 240 schools have been damaged by 2,679 regime airstrikes from Jan. 1, 2023 up to May 12. At least 333 schools have been destroyed by regime attacks since the military coup on Feb. 1, 2021, according to DVB data. The regime renewed its April ceasefire on May 6 until the end of the month.

Indian Army operation kills 10 on Myanmar border

The Indian Army reported that it had killed at least 10 militants in an ongoing operation in its northeastern Manipur State near the India-Burma border. Reuters reported in November that Indian militant groups that sought refuge and fought in Burma’s conflict had begun crossing the border back into India.

“Ten [militants] were [killed] and a sizable quantity of arms and ammunition have been recovered,” the Indian Army shared in a post on social media on May 14. It was referring to a fighting between its forces and unnamed armed groups along the 1,021 mile (1,643 km) long India-Burma border.

Intercommunal violence in India’s Manipur State, which erupted in May 2023 has led to the deaths of nearly 260 people, with more than 60,000 displaced from their homes over the last two years. The state’s 3.2 million residents have been divided into two ethnic enclaves, a valley controlled by the ethnic majority Meiteis and the minority Kuki-dominated hills.

United Wa State Army stages another public execution

The United Wa State Army (UWSA) executed one of its members in Pangsang, the Wa Self-Administered Zone of northern Shan State, on Wednesday. The man was sentenced to death by the UWSA for selling ammunition to the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) without authorization, a resident told DVB. Pangsang is located 169 miles (271 km) east of the regional capital Lashio.

The resident added that the driver who allegedly helped transport the man convicted was sentenced to prison, but the length of his sentence is unknown. The man was convicted of selling 32,000 stolen bullets for over 400,000 Chinese yuan ($55,000 USD), according to a court report. He was arrested by the UWSA during a deal with the TNLA, a Wa media outlet affiliated with the UWSA reported.

The UWSA carried out a previous public execution in Hopang town on Oct. 30. Hopang is located 92 miles (148 km) east of Lashio. The UWSA was handed control of Hopang and neighbouring Panlong by the Brotherhood Alliance, which includes the TNLA, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Arakan Army (AA), on Jan. 10, 2024 after the towns were seized from regime forces during Operation 1027.

News by Region

ARAKAN—Kyauktaw Township residents told DVB that three civilians were killed and five were injured by airstrikes on Wednesday. This comes one day after airstrikes killed 13 civilians in Rathedaung Township on Tuesday. Rathedaung and Kyauktaw came under AA control one year ago.

The AA condemned the airstrikes on civilian areas in a statement on May 14. Kyauktaw is located 60 miles (96 km) north of the state capital Sittwe, which is controlled by the regime. The Brotherhood Alliance announced a unilateral ceasefire on March 30, which was extended until May 31.

MANDALAY—Mogok Township residents told DVB that a man died while in TNLA detention – three days after his arrest – on May 11. Mogok, located 124 miles (200 km) north of Mandalay city, came under TNLA control on July 24.

“We had nobody to turn to, or appeal to [for justice],” a family member of the victim told DVB on the condition of anonymity. The family added that the man was arrested for shouting at TNLA members on May 8. Relatives who saw the body said that he had bruises and a broken nose.

SHAN—Sources close to regime authorities in Lashio told DVB on Wednesday that former ward and village administrators were reappointed. Lashio is located 174 miles (280 km) northeast of Mandalay and 243 miles (391 km) north of the Shan State capital Taunggyi.

“They’ve brought back their original personnel,” a source told DVB on the condition of anonymity. The MNDAA withdrew from Lashio and completed its handover to the regime on April 21 as a part of its China-brokered ceasefire agreement signed on Jan. 18.

Lashio residents told DVB that the administration has yet to resume full operations due to ongoing repair work at its offices and at Lashio Airport, which were damaged during fighting between MNDAA and regime forces. No announcement has been made about when Lashio Airport will reopen.

(Exchange rate: $1 USD = 4,400 MMK)