FROM THE DVB NEWSROOM

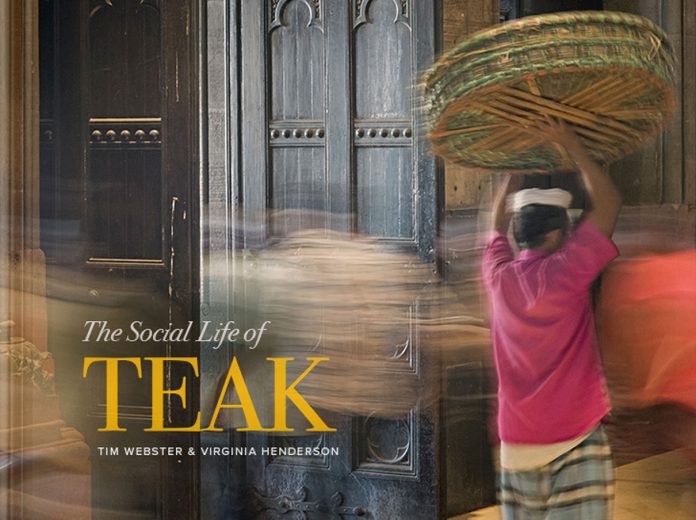

Extraordinary stories from people in Myanmar whose lives have been shaped by their connection to teak are told in a new book The Social Life of Teak, which traces human interaction with a wood that has been revered, exploited and fought over for centuries

Authors Tim Webster and Virginia Henderson photographed and interviewed people in many parts of Myanmar as they collected stories across the teak zone in South and Southeast Asia and beyond.

From planters and forest rangers to merchants and high officials, their book throws light on the ways that this highly-prized tropical hardwood has been harvested, traded and crafted over time. Perspectives range from people working with teak to indigenous Kayah people who see the forest as a spiritual home, a larder and a refuge.

“I love living among trees I’ve planted. It’s very peaceful.”

TEAK PLANTER, TAUNG NA WIN FOREST RESERVE, PEGU YOMA.

Storytellers speak candidly of respect for natural harmony and industrial endeavour, and their desires for fairness, opportunity and autonomy. Matters of legacy and custody rub against ideas of access, equity and ongoing struggles over rights to a remnant natural bounty.

Interviews were conducted in Myanmar from 2015-2019, a period the authors describe as ”that brief window of democratic possibility.” It was a time of forestry reform after the feeding frenzy of the 1990s when the military government’s appetite for funds, coupled with mechanisation, destroyed entire forests.

“During that open time of democratic transition before the coup, people were willing and able to speak about what was happening in forestry, reflecting honestly on what had worked and what hadn’t,” said Virginia Henderson. “They shared ideas of how to rein in the excesses and how efforts to enshrine sustainability wilted in the face of hunger and financial gain. These are rare stories captured at a special time.”

“The military government and its cronies degraded our forests and earned the income. Everybody knows.“

Forest pathologist, Yezin, Myanmar.

The authors told DVB their rarest insights came thanks to an official invitation from the Myanmar government to talk to people at the state-owned extraction company, Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE).

A forester from Pakokku recounted investigating cases of illegal extraction and being sent to arrest a small businessman who had illegally cut a few trees, even though his shop was beside a compound holding 10,000 teak logs.

“I asked my supervisor, why don’t you arrest the big company? If you arrest them you can get more of the illegal teak? The company was in the name of the daughter of a general. My superior took action. He reassigned me far away from Yangon.”

Forester, Pakokku, Myanmar.

The book shows how teak is used for both basic needs and the finest cultural expressions.

“Around here there used to be all kinds of fields. Most people don’t own or work in them any more. Today there are few buffalo and oxen so this village doesn’t use many cartwheels. Last year we made 40. This year we made 10.”

Cartwheel maker, Kyi Taung Kan village, Nay Pyi Taw.

Personal accounts speak of change and survival. One man described how he spent 12 years planting 500 acres of teak each year for the Forest Department, calculating that he had planted 3,240,000 trees over that time. He said he no longer recognised the places where he once lived and worked.

“Forests and plantations have become rice paddy fields. Dams have flooded landscapes. There were big teak forests here. Now there’s not a single tree left. The sadness I feel is not for myself. It’s a great sense of loss of everything.”

Forest department worker, Pauk Kaung, Bago Yoma.

A photo that reflects how much has changed in Myanmar since the book was researched features Tin Thit posing in front of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw. He is now Minister of Defence in the National Unity Government (NUG), which was formed by ousted parliamentarians after the 2021 coup.

“My village Kyi Daung Kun was once surrounded by rich teak forests. Now it’s all gone. The forest was an ideal hiding place for the Burma Communist Party fighters and it also harboured malaria mosquitoes. These are the reasons the military government gave for cutting them down.”

Tin Thit, Nay Pyi Taw.

At a recent book launch in Chiang Mai, Thailand, the authors spoke of their experiences researching The Social Life of Teak, describing by the authors as a listening project, an enquiry into the significance of teak.

“Listening to hundreds of people across thousands of kilometres express their connections to teak laid bare confounding inconsistencies, frightening destruction, staggering quantities, overt inequalities, astonishing creativity and remarkable resilience,”

Find out more in the DVB Newsroom interview with Tim Webster and Virginia Henderson on Monday, Dec. 11. For information about The Social Life of Teak, visit www.timwebster.com.au.