This is the first article in a two-part series examining the relationship between sectarian violence and resource distribution in a changing Burma. The second part can be read here.

The recent conflagrations of sectarian violence in Burma have shocked the country and the world, having left thousands displaced, scores dead, and millions of kyat of property damaged.

They have also left a series of fragmented analyses, as commentators struggle to make sense of the slaughter. On one hand, some – incapable of seeing beyond a ‘big-bad Burma state’ paradigm – believe that the state is behind the current violence, and/or that disgruntled generals are orchestrating attacks from behind the scenes to legitimate the military’s institutional role. On the opposite end of the spectrum others argue that a deep-seated racism, fomented under the long years of the military regime, is now being ‘unleashed’ as the military relaxes controls.

Both of these perspectives draw from evidence that is partially correct – the military-state has spurred internal divisions and likely has orchestrated violence in the past; there is racism in Burma society against dark-skinned people. But neither encompasses the entire story.

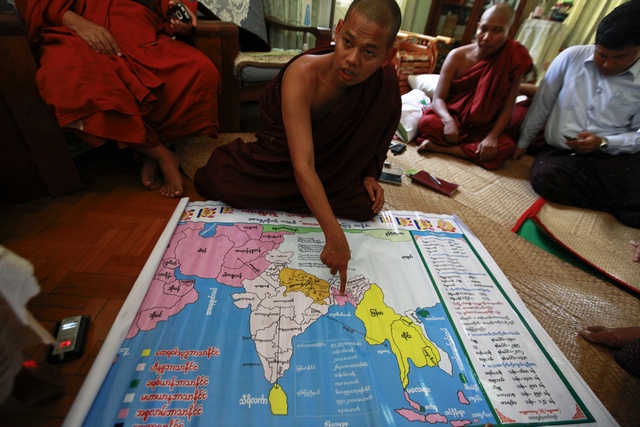

The Buddhist-monk-led anti-Muslim campaign that has generated much collective hatred cannot be construed as emerging from a conspiratorial state elite. Likewise, such hatred cannot be imagined outside of the context of state institutions which insist upon eternal racial and religious differences: ID cards demand that babies at birth be given either – but not both – a “Muslim” or a “Burmese” identity; state-enforced birth-limits directed only at certain Muslim communities present them as second-class citizens and demographic threats.

But understanding the spontaneous explosions of violence requires a consideration of the socio-economic context in which these attacks are occurring. Increasing economic stratification can help explain the growth in anxieties generated by concerns over resource distribution. The exclusion of perceived foreigners can be interpreted as an inter-class attempt to construct a community of legitimate claimants to this finally-growing – but unequally distributed – pie.

But this exclusion may not stop with these particular “others”. These intensifying feelings of being left out, combined with the failures of citizens and political leaders to articulate a conception of an inclusive Burmese civil political community, creates opportunities for a violence that may be uncontainable and may continue to attach to others who may seem suddenly or irreconcilably ‘foreign’. The risk is that Burma tears itself apart in its search for its ‘authentic’ core.

The Instability of Scapegoating

When Arakanese Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims first clashed in western Arakan state last summer, the violence was a regional issue. But it did not remain there. Discourse across Burmese society about the Rohingya soon exploded, with Buddhist monks, political leaders, and even other ethnic minority groups weighing in. They were all in agreement: the Rohingya were threats to the nation, were not part of it, and must be expelled.

A tiny ethnic minority kept in concentration camp conditions for years, periodically targeted for mass abuse and expulsions was suddenly imagined as a threat to the entire polity? How to make sense of this? Could this violence – and the violent discourse surrounding it – be interpreted as a tactic for building a collective ‘in-group’? Indeed, as the long years of the military regime gave way to a new, more ‘open’ society, the violence seemed to work as a way of trying to establish the definitions and limits of that new society.

This was especially true given the long-standing historical animosity between the majority Burmans and Burma’s other ethnic minorities. These ethnic minority groups, who scholar Matt Walton has identified as seeming “to enjoy only conditional membership in the national community… always subject to suspicion of disloyalty”, were suddenly being hailed as ‘indigenous races’ connected to the blood and soil of the nation.

These ethnic groups played their part, quickly drawing a distinction between themselves and the Rohingya. The National Democratic Front, a coalition representing eight nationality parties, was unequivocal: “‘Rohingya’ is not to be recognized as a nationality.”

But as “the inside” was apparently being established through the process of eradicating “the outside”, violence overflowed. From its initial scapegoat, violence began to be directed at Burma’s other “others”: in the central town of Meikhtila, in environs north of Rangoon, and in the northeastern city of Lashio, respective mobs have turned on Muslim citizens, burning property and murdering scores.

Critically, these Muslim citizens have been integrated into Burma society for generations, and so it is more accurate to say that they are being turned into”others”. Muslims in central Burma — who have no connection to Bangladesh — are now being called “Bengali“. This is also the name Burmese state security agents insist Rohingya call themselves.

Similarly, a Chinese Muslim (Panthay) colleague – whose light skin means she does not ‘look’ like the Muslims that Burmese often derisively refer to as kalar – told me last month in Rangoon that she is afraid that the violence will spill over to them as well. Days after our conversation, Panthays had their cinema burned to the ground in Lashio.

This progression of violence suggests that scapegoating is potentially uncontainable – from Rohingya to all Muslims, from Rohingya to all dark-skinned people, and potentially beyond.

For instance, in Rangoon I came across a number of propaganda pamphlets urging Buddhists to protect their race and religion. While the covers are adorned by fetuses (invoking Muslim population threat) and prehistoric beasts (invoking the supposed Muslim desire to consume the Burma nation), the texts implore readers to beware “the other races”, or the “evil other-race husbands”, which are terms eminently re-deployable to any group constructed as “other”.

But this cuts both ways: once one group is identified as “not part of” Burma, or “incompatible” with “our traditions”, Burmese citizens or traditions themselves are put into question, are even potentially undermined.

From animosity to violence

All of this animosity still does not explain the move to sporadic, spontaneous violence. Looking at economic indicators as a proximate cause provides helpful insight. Stanley Tambiah, in a study close to the Burmese case, shows how as far back as 1910 Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka were justifying violent attacks against non-Buddhists through the language of economic victimisation.

Tambiah cites a tract written by a Buddhist monk that argues that “the ‘merchants from Bombay and peddlers from South India’… trade in Ceylon while the ‘sons of the soil’ abandon agriculture and ‘work like galley slaves’ in urban clerical jobs.”

A similar phenomenon occurred in Burma and remains relevant today. Many Burmese still reference how Chettiars – money-lenders from Tamil Nadu – expropriated hundreds of thousands of hectares of land when the Great Depression undermined the ability of Burmese borrowers to repay agricultural loans.

[pullquote] “Increasing economic stratification can help explain the growth in anxieties generated by concerns over resource distribution” [/pullquote]

While Sean Turnell, author of a book on the period, tells me that these Chettiars were mostly non-Muslims (either Hindus or Christians), their South Asian physiognomy has largely been conflated with Muslim identity, especially given that today, as a 2002 Human Rights Watch report illustrates, “many Muslims are businessmen, shopkeepers and small-scale money changers.”

HRW argues that this position in the economy “means that [Muslims] are often targeted during times of economic hardship.” The difference now is that while the whole economy is still poor, there are signs that small swathes are improving drastically. As I’ve argued elsewhere, there is a palpable sense of anxiety in Burma today deriving from the speed of change and the feeling of missing out on the spoils associated with those changes.

And while there is no time-series data tracking increasing inequality in Burma over the past years, rapid growth that is concentrated in extractive industries will often accrue to narrow elites – especially when rampant land-grabs attend it, and when compensation – if given at all – considers only the market price today, not what it will become in a changing Burma.

Given all this, when political leaders such as Aung San Suu Kyi tell poor farmers in places like Latpadaung that they have to respect contracts written by the previous military regime and so must hand over their land to Chinese companies in the name of a rule of law that she has always insisted did not exist when those contracts were written, average people may begin to suspect from this utter nonsense that ‘democracy’ means nothing more than their freedom to continue to be exploited.

Thus abandoned, people take matters into their own hands. This does not mean that sectarian violence is inevitable (it has not occurred in Latpadaung, for instance), but rather that some in these situations lash-out at what they misperceive as their exploiters (and with the potential aim of looting the resources and appropriating the market positions of those one rung above them).

Within this logic, it is not surprising that the city of Meikhtila, long deeply-impoverished but now sporadically-growing by dint of its increasing importance in linking Rangoon with Mandalay, has become a site of sectarian strife. It is no wonder the Rohingya are being displaced and contained in an area where a Special Economic Zone is being built. Most convincing here is that the Buddhist ‘969 movement’ is above all an economic boycott that targets Muslim businesses.

Matt Schissler’s exploration of working-class Burmese Buddhist anti-Muslim sentiment shows how economic grievance fuels the legitimacy of that movement: whereas Buddhists can observe how Muslims do not always convert wives or children, that they often respect Buddhism, etc, demagogues and average people alike perceive Muslim wealth. In this context the 786 symbol that adorns Muslims shops signifies to Buddhists not only halal food but also a desire to dominate the economy.

As Maung Zarni, visiting fellow at London School of Economics, puts it, “some militant Buddhist preachers… effectively scapegoat the country’s Muslims for the general economic hardships and cultural decay in society, portraying the ethnic Burmese as victims at the hands of organised Muslim commercial leeches and parasites.” Commentator Sai Latt points out that economic exclusion is not a mere pretext for physical violence and exclusion, but rather directly leads to it.

This is particularly relevant now given that the conventional wisdom in Burma today assumes that economic development will act as a panacea for Burma’s internecine problems. It may do precisely the opposite.

Elliott Prasse-Freeman is Founding Research Associate Fellow of the Human Rights and Social Movements Program at Harvard Kennedy School’s Carr Center for Human Rights. He is also a PhD candidate in Anthropology at Yale University

-The opinions and views expressed in this piece are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect DVB’s editorial policy.