Former information minister and presidential spokesperson Ye Htut has turned over a new leaf. No longer charged with the Sisyphean task of polishing the Burmese government’s image, he now spends his days as a senior visiting fellow at the Singapore-based Institute for Southeast Asian Studies. Along with the new job title has come a surprising new set of opinions on the Arakan State crisis.

In a new paper titled “Rakhine Crisis Challenges ASEAN’s Non-Interference Principle,” released by ISEAS, Ye Htut departs from a career built on suppressing the use of the name “Rohingya,” rejecting that community’s right to citizenship and defending the military’s human rights abuses. Instead, using the word “Rohingya” 33 times in seven pages, Ye Htut calls for citizenship for the Muslim minority and humanitarian intervention by ASEAN to end their persecution.

Ye Htut spoke to Coconuts Yangon by email on Friday and explained how working in a new, scholarly environment in Singapore has induced his change of heart on one of Burma’s most contentious issues.

In a move we would never have seen a year ago, Ye Htut and his co-author Hoang Thi Ha start off the paper by criticising the Myanmar government’s refusal to recognise the Rohingya by their chosen name.

“Framing the problem in a way that can effectively facilitate a regional approach to the problem is in itself a difficult challenge. Myanmar has, for example, rejected any use of the term ‘Rohingya,’” they write.

This reads like a criticism of State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, whose National League for Democracy party ousted Ye Htut from his post as information minister in the 2015 general election. In May, Suu Kyi brought smiles to the faces of Buddhist nationalists when she instructed foreign diplomats not to use the term “Rohingya.”

But the Burmese government’s rejection of this ethnic designation predates Suu Kyi’s election by years.

Ye Htut himself said at an ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Retreat in January 2014: “Myanmar people and the government do not accept this name Rohingya.”

In March of that year, he announced that the Burmese government would not include families in the national census if they identified as Rohingya.

Then, shortly after his party lost the general election in November 2015, he said: “Our government’s stance is that we wholly reject use of the term ‘Rohingya.’”

The former minister’s change of heart about the use of the term is tied to his newfound — though partial — acceptance of the group’s quest for citizenship. In a series of recommendations aimed at ASEAN, Ye Htut writes:

“A sense of compromise should be inculcated to bridge the two apparently irreconcilable positions regarding the term ‘Rohingya.’ One proposed solution is to use ‘Rohingya’ as a name for a community (like the Chinese, Indian and Nepali). This needs to be a package deal that requires compromises from all sides: (i) the Rohingya should renounce their quest for ethnic indigenous status and only seek citizenship; (ii) the Myanmar government should accept that Muslims in Rakhine [Arakan] have a right to self-identity and accelerate a proper and transparent process for their naturalization.”

Ye Htut told Coconuts Yangon that seeking inclusion for the Rohingya among Burma’s 135 “national races” would be futile. Therefore, seeking citizenship status analogous to that of other recent immigrant groups in Burma is “the only way to solve the problem.”

“The [government of Burma] and Myanmar people [will] never accept Rohingya as ethnic groups like Bamar, Rakhine, Kachin, Kayin, etc. [Burmese people know that] under British rule from 1824 to 1948, British official censuses and reports never mention the Rohingya name; it only appeared in the 1950s. Even Western embassies used the word ‘Bengali’ until 1992,” Ye Htut said, stressing that the only practical path to citizenship for the Rohingya would require the community to concede that they are relatively recent immigrants from Bangladesh.

He also thinks the Rohingya should embrace compromise rather than fussing over that distinction.

“Nearly all Bengalis do not understand the difference between ethnic rights and citizenship rights. Because of their religious leaders’ propaganda, they believe that only ethnics [national races] can enjoy citizenship rights in Myanmar,” he said, momentarily switching to his spokesman voice.

He said citizenship for the Rohingya must be granted through the 1982 Citizenship Law and should follow the model of Myebon township, where displaced Muslims were invited to apply for citizenship in 2014.

“Read about the pilot project in Myebon township in 2014, where 80 percent of Bengalis received citizenship,” he said, reminding us that old habits die hard.

But according to Reuters, out of 1,094 Muslims in the township who took part in the program, 209 were granted citizenship, and many were members of communities other than the Rohingya. Many refused to participate because the program required them to register as “Bengali.”

Ye Htut clarified that in a future program, they should be designated as “Rohingya.”

Rohingya citizenship is not the only new cause Ye Htut has taken up. He has also changed his tune on the issue of ASEAN intervention in Burma’s “internal” issues.

At the same 2014 ASEAN retreat mentioned above, Ye Htut said: “There were issues occurring between people of different religions in Myanmar in previous years. These problems were solved by the Myanmar government and [Myanmar] people because this was an internal issue for Myanmar.”

He went on to explain that the Burmese government would not accept discussion of the plight of the Rohingya community by ASEAN during Burma’s chairmanship of the regional bloc. From then until today, the Burmese government has deflected criticism from critics in ASEAN by invoking the association’s principle of non-interference.

But now, the former spokesman says it is “increasingly untenable for ASEAN to insulate itself from this unfolding crisis behind the shield of non-interference.”

“Beyond its political and security implications, the Rohingya issue has dealt a reputational blow to the credibility of the ASEAN Community that was launched last year. The notion of a caring and sharing community rings hollow in the absence of a meaningful response to this latest humanitarian challenge,” he writes in the paper.

He told Coconuts Yangon that this change of heart was motivated by concerns about terrorism.

“After the October 9 attacks, the situation in northern Rakhine State reached a new level. Ordinary Muslim villagers have been radicalised after the 2012 communal violence. That requires new initiatives to solve the problem. ISIS is starting to use the northern Rakhine crisis to recruit Muslims from Malaysia and Indonesia,” he said.

“Myanmar can no longer see it as internal security operation and needs to work with other ASEAN countries in an anti-terrorism campaign.”

Moreover, he has also come around to calls for independent documentation of the crisis in northern Rakhine State.

In October 2015, Fortify Rights released a report titled “Persecution of Rohingya Muslims,” which said there was “strong evidence” to “infer genocidal intent by security forces, government officials, local Rakhine, and others.”

Ye Htut denied the report’s claims without addressing them in detail. Instead, he said: “They made the report intentionally to make the situation complicated in Rakhine State … It is an intentional plot when the election is approaching.”

[related]

Ye Htut may still believe that was the case back then. But now, he calls on ASEAN to “persuade Myanmar to allow access by ASEAN representative[s] to the troubled areas, focusing on needs assessment for humanitarian assistance.”

“With conflicting narratives from the Myanmar government and Rohingya groups inflaming resentment, an objective evaluation of the situation by ASEAN is a good first step toward reconciliation,” he writes in the ISEAS paper.

Worsening conditions in Burma, a job outside government and perhaps some self-interest may have helped the former information minister warm up to the international perspective on Burma’s most sensitive issue.

In his own words: “My concept about the Rohingyas’ demand for [national race] status has not changed. But the academic atmosphere at ISEAS has made me understand reality more and more.”

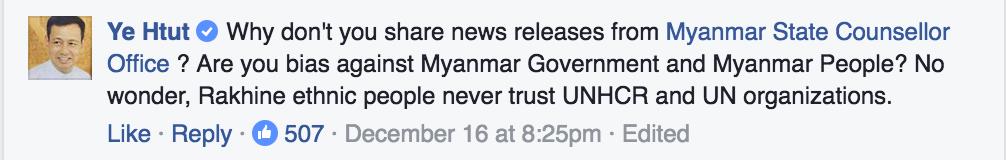

Whether U Ye Htut harbours any of his old sentiments toward the Rohingya is hard to assess. The “Facebook Minister” has remained active on social media, even after his tenure as government spokesman ended. A few days before his ISEAS paper was published, he left a comment under a photo posted by the United Nations Information Centre in Yangon. The photo depicts a Rohingya man crying and praying, and the caption quotes him as saying: “If the authorities have nothing to hide, then why is there such reluctance to grant us access? Given the continued failure to grant us access, we can only fear the worst.”

The top comment, left by the former minister, says:

Calling for balanced coverage doesn’t necessarily mean Ye Htut condones the government’s actions. Indeed, he does the opposite of that in the ISEAS paper. But until his public image matches his opinions in the paper, his followers may continue to see him as he has been seen in the past.

This may not change anytime soon. He told Coconuts Yangon he would not use his public platform to galvanise public support for Rohingya citizenship.

“I am not activist,” he said. “I only share my academic view.”