On Valentine’s Day, an event called “Loving Myanmar@CMU” was held at the Faculty of Humanities Department at Chiang Mai University (CMU) on Feb. 14. A professor in the Burmese Division at CMU told DVB that this event allowed Thai students, who are studying Burmese, to practice their language skills and learn more about Myanmar culture. Read more and check out our photo essay.

Showing love for Myanmar on Valentine’s Day in Thailand

How the US funding freeze and aid suspension affects Myanmar refugees

Guest contributor

Pacifist Farooq

The 90-day suspension of funding to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) by the Trump administration in the U.S. has affected millions of people around the world.

The deprivation of medicine and treatment to patients with HIV/AIDS across the globe, flight cancellations for refugees in Malaysia, and the shutdown of field hospitals in refugee camps in Thailand, including in the world’s largest refugee camp in Bangladesh.

President Trump’s executive orders have further pushed the vulnerable to the brink. Among those most affected are the Rohingya, who have faced decades of persecution and genocide in Myanmar simply because of their race and Islamic religion.

On Jan. 20, the Trump administration withdrew all U.S. foreign aid, including Bangladesh, which hosts over one million Rohingya refugees who survived the 2016-17 military crackdown in northern Arakan State, which has been called ethnic cleansing by the U.N. and genocide by the U.S. in 2022.

It’s also the basis for a 2019 genocide case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and an arrest warrant request for Min Aung Hlaing on crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court (ICC) by its Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan.

Following a meeting between Khalilur Rahman, the high representative of Bangladesh’s interim leader Mohammad Yunus, and the U.S. embassy in Dhaka, it confirmed that life-saving food and nutritional support for the Rohingya sheltering in Bangladesh are exempted from the U.S. aid freeze.

However, site management and landfill activities were not included, and the operations of at least five hospitals in the Bangladesh refugee camp were suspended due to the U.S. cuts, according to Bangladesh’s Office of Refugee, Relief, and Repatriation (RRRC) Commissioner Mizanur Rahman.

The decision to suspend funds will have a devastating impact on the lives of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. The refugee camps around Cox’s Bazar is an already organised hell fenced with barbed wire, where the refugees are fully dependent on World Food Programme (WFP) assistance.

Many rarely have access to fish in their meals, except for a few of those who are versed in English and fortunate to find a job at an international non-governmental organization (NGO).

I know this because I lived there for over five years. When we try to leave the camp to work, their fates end up with detention and deportation back to the refugee camps.

Moreover, formal education is unavailable for Rohingya children, who can only receive up to class eight of non-formal education from NGOs. The Rohingya youth are feeling hopeless and desperate.

As a result, they can easily be convinced to join armed groups. Besides the shortage of food and limited education, healthcare is far worse. Due to congestion and malnutrition, refugees are usually affected by measles, scabies, and hepatitis C.

The healthcare facilities can only provide medication and treatment to patients in critical condition because of insufficient funds. The situation of Rohingya refugees is becoming appalling.

A reduction in aid means a deepening shortage of food and malnutrition, destruction of hundreds of children’s lives, and limited access to life-saving medications, maternal health services, and vaccinations, increasing the risk of outbreaks of disease.

The U.S. funding freeze will not only increase the vulnerability of Rohingya in the Bangladesh refugee camps but it will also threaten the existence of Rohingya remaining in Arakan.

Most of them are internally displaced persons (IDPs). They are somehow surviving by eating whatever they can. The insecurity, military blockades, and movement restrictions, have severely reduced the ability of humanitarian aid deliveries to reach those in need.

With their movement restricted even from one village to another, the Rohingya have been facing a severe humanitarian crisis for many years. The suspension of funds will further deteriorate the situation and force them to leave Arakan for neighbouring countries to avoide famine.

The suspension of aid may also jeopardise Rohingya advocacy and political representation. The Rohingya have long been struggling for political representation both inside and outside of Myanmar.

In Myanmar, we are sometimes labelled as “Bengali”, sometimes “Muslim”, and at other times “foreigners”. The same is true with Bangladesh.

For those of us who have survived the genocide in Myanmar and took refuge in Bangladesh, we have no documents identifying us as Rohingya but have become known as “forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals.”

Everything for us is decided by others. We don’t even have the right to decide our own name. The loss of financial support could further worsen the Rohingya representation in policy-making processes.

Regarding Rohingya advocacy, many of the organizations that advocate for Rohingya rights are dependent on U.S. funding. These organisations have done some excellent jobs, such as documenting human rights violations committed by the Myanmar military and lobbying for legal action at the ICJ and the ICC.

Without U.S. funding, these human rights organisations may find it difficult to run advocacy programs that provide legal aid and document the recent human rights violations committed against the Rohingya by both the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA), a Buddhist Rakhine nationalist armed group that has gained control of fourteen out of seventeen townships in Arakan.

Most importantly, the withdrawal of funding could weaken international pressure over the Myanmar military regime, which has killed over 6,263 civilians and has detained over 21,793, arresting over 28,526 in total since the 2021 coup.

Over 3.5 million people have been displaced from their homes in Myanmar, according to the U.N. Tens, or potentially hundreds, of thousands of citizens have left the country.

The injustice and suffering imposed on innocent civilians nationwide is totally unjustifiable and unbearable. In the northern part of Arakan, even though the military is absent, its landmines are killing civilians there almost every day.

Sometimes I feel like I’m living in a jungle where there are no rules of law and accountability for the crimes perpetrated in my country. For years, the U.S. has used aid as a tool to pressure the Myanmar military into respecting human rights and democracy.

The USAID has played a crucial role in funding organizations that monitor human rights abuses, support refugees, and promote democracy. The suspension of funds will, in fact, weaken the international leverage on the Myanmar military to be held accountable for the genocide against the Rohingya and the crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, war crimes, and mass murder, committed against other ethnic nationalities across Myanmar.

Furthermore, President Trump’s funding freeze hits the students and scholars from Myanmar. During a signing ceremony at the White House, The president announced that he had “blocked $45 million [USD]” for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) scholarships for Myanmar students.

Those students whose scholarships were suspended are among the future leaders who could contribute to a more diverse and inclusive Myanmar. Those who did not have the opportunity to study are usually narrow-minded, illiberal, and racist.

These kinds of moves may hinder Myanmar from strengthening diversity and inclusiveness and could have a long term negative impact on the Rohingya community.

President Trump’s executive orders also limited the operations of Mizzima, an independent news media banned after the 2021 coup. Since then, all the independent media have fled, mostly to Thailand, as their licenses were revoked for reporting on human rights abuses by the military.

The independent media play a key role in educating the public about how to protect minority groups, including the Rohingya. For example, recent reports exposed that at least 250 Rohingya, who were due to be released from detention, were not by the regime.

If there is no independent media, there are no ways of such news getting out of Myanmar. Yet many news outlets, including Mizzima, are quite hesitant in covering the abuses against the Rohingya being perpetrated by the Arakan Army (AA).

Indeed, many Myanmar media were and are complicit in the genocide against the Rohingya. Nevertheless, there are very few independent news media left to report on these issues.

If we lose independent media, regime-controlled media would dominate the information space, spreading propaganda, disinformation, and hate speech against us again.

With the U.S. retreating, China is more likely to fill the media void and further expand its influence in Myanmar. It will further strengthen the military regime, which will lead to economic and strategic interests overtaking human rights and democracy. This will further exacerbate the Rohingya crisis.

Without sustained international support, the chance for Rohingya to have justice for the genocide is very slim. We might face even greater political isolation, reduced chances of regaining citizenship, and prolonged displacement.

For the Rohingya, the U.S. funding freeze and aid suspension is not just a financial setback, but it’s a matter of survival and existence on this planet.

Pacifist Farooq is a Rohingya poet, academic, and author of A Lost Bird Between Genocide and Displacement. He is now based in Malaysia.

DVB publishes a diversity of opinions that does not reflect DVB editorial policy. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our stories: [email protected]

Karenni State provisional government expands administration

The Karenni State Interim Executive Council (IEC), a provisional government established by resistance forces in 2023, announced on Feb. 10 that it has expanded 16 township-level administrative bodies in Karenni and in southern Shan states, located 262 km east of the capital Naypyidaw, along the Myanmar-Thailand border.

“Each township administration must include at least one woman, and representatives are elected by villagers through an election-style process. Additionally, we have included members from ethnic revolutionary organizations, with a minimum of one and a maximum of four members, alongside four to nine public representatives. This creates a hybrid-style township administrative body,” Khu Oo Reh, the IEC chairperson, told DVB.

The Karenni IEC formed township administrative bodies in Hpruso, Demoso (East), Nanmekhon, Mese, Ywa Thit, and Pekon townships. The latter is located in southern Shan. Furthermore, 16 police stations have been established across these townships.

“The main weakness is the lack of staff in the Home Affairs Department, which limits the provision of adequate public services. While people now have access to courts for legal proceedings, issues arise when cases involve military personnel. Since they are armed, people are often afraid to file complaints. When such complaints are brought to the IEC, responses can be weak due to limited human resources and administrative capacity,” a Demoso resident told DVB.

The Karenni IEC announced on Feb. 11 that all visitors and tourists in Karenni State must obtain a pass for safe passage. It also reported that it has generated over 5.5 billion kyats ($1.2 million USD) in revenue during 2024.

In its annual departmental performance report, the Karenni IEC detailed its revenue sources: 31 percent from tax collection, 29 percent from contributions by the National Unity Government (NUG), 28 percent from international organizations, and 12 percent from other sources.

The IEC was established in June 2023 as a provisional government and it operates under a federal democratic model, which has been cited as an example for the rest of Myanmar.

It has established 11 departments, including four sub-departments under the Home Affairs Department: the Public Administration Department, the Immigration Department, the Emergency Relief Department, and the Karenni State Police Department.

Karenni resistance forces claim full control over six towns in Karenni State, including Mese on the Myanmar-Thailand border.

Following an offensive launched on November 11, 2023, they seized most of the Karenni State capital Loikaw, but in June last year the military regained control of it. Currently, 80 percent of Karenni State, which historically includes parts of southern Shan, is under IEC control.

The regime in Naypyidaw controls Loikaw, Bawlakhe, and Hpasawng.

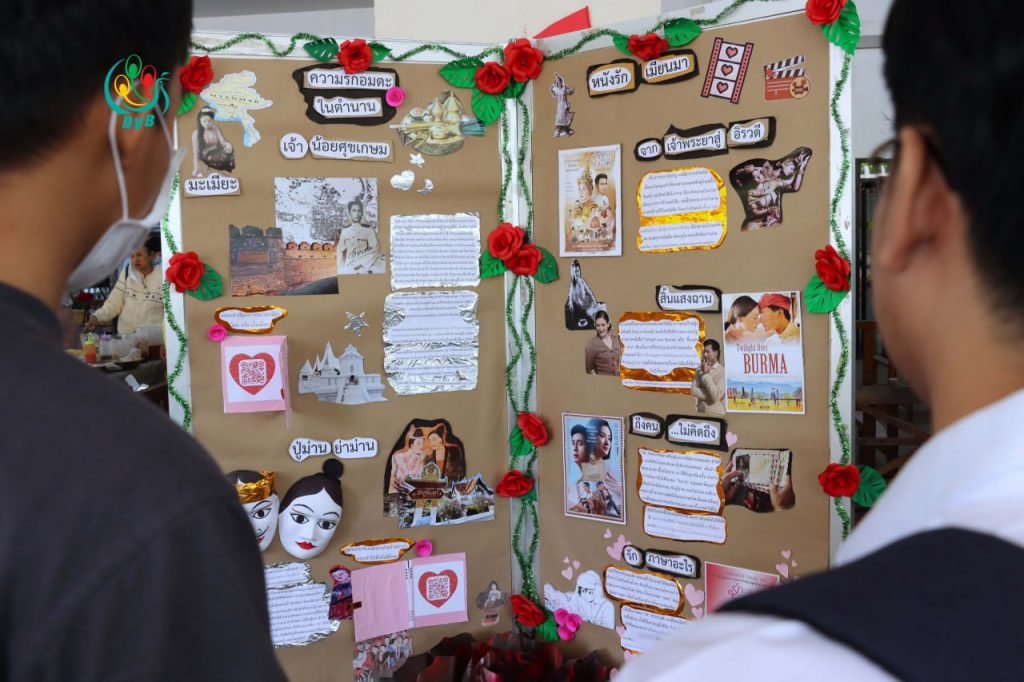

Loving Myanmar on Valentine’s Day in Chiang Mai, Thailand

On Valentine’s Day, an event called “Loving Myanmar@CMU” was held at the Faculty of Humanities Department at Chiang Mai University (CMU) on Feb. 14. A professor in the Burmese Division at CMU told DVB that this event allowed Thai students, who are studying Burmese, to practice their language skills and learn more about Myanmar culture.

“There are various competitions today. There is a Burmese speaking skill competition, a Burmese language singing competition, a calligraphy competition, a quiz competition, and even a photography competition,” said Ampika Rattanapitak, an assistant professor in the Burmese Division of the Department of Eastern Languages at CMU.

CMU opened its Burmese language department eight years ago for Thai students interested in learning the Myanmar language. “I want to know more about Myanmar, like Myanmar food, how to speak, how to listen, how to read and how to write [Burmese]. And this event shows you lots of things,” said Vachiravitch, a third-year political science student at CMU. Myanmar residents of Chiang Mai participated in the event, selling traditional gifts and food.

The rights violation of freezing US aid

As the Trump administration freezes funding to Southeast Asian initiatives, Beijing is stepping in to fill the void

Benedict Rogers for UCA News

Last month, within days of his inauguration, US President Donald Trump announced a 90-day freeze on foreign aid, and the U.S. State Department issued a “stop-work” order to all recipients of U.S. foreign assistance.

The dramatic measure threatens to have devastating consequences for millions of people around the world — especially those most vulnerable to poverty or displacement as a result of war or persecution — and those who defend basic human rights on the frontlines of the fight for freedom.

The United States is the world’s biggest international aid donor, spending $68 billion USD in 2023. The State Department notice appears to impact everything, from development assistance to humanitarian aid to civil society support and military aid.

A new administration is perfectly entitled to review its spending priorities. Given the size of U.S. aid spending, it is certainly within the new president’s rights to review how those funds are used.

It is also valid to argue that the rest of the world should reduce its dependency on the generosity of a single country — the United States.

The wealthy, developed, and free world should share the burden of caring for the world’s most vulnerable, and defending our values of freedom, together.

The European Union, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and wealthy democracies in Asia — Japan and Korea for example — should do more.

And long-term, there may be good reasons to re-order the aid budget — to root out corruption, to end the funding of politically-motivated, ideological agendas that don’t serve the needs of the poor or the interests of the U.S., and to ensure that taxpayers’ dollars are well-spent.

There is also a legitimate debate to be had about the balance between aid and trade in helping to lift people out of poverty.

There is the old adage — “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime”. There is much to be said for investing funds in skills development and enterprise.

And yet, there are emergencies around the world where people in dire need were dependent on U.S. aid for their very survival — and now have had their very legs cut out from under them and their lives literally jeopardized.

And there are struggles for freedom which it is both consistent with the values of — and in the interests of — the free world to support.

It is in no one’s interests — except those of repressive, authoritarian dictatorships — to see brave human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists, religious freedom champions and dissidents cut off from funding and thrown to the wolves.

In Myanmar, where famine looms and the U.S. is the single largest aid donor, one humanitarian worker described the situation as “mayhem.”

This week, it was reported that a 71-year-old woman, a refugee in a displacement camp along the Thailand-Myanmar border, died after she was discharged from a U.S.-funded healthcare facility and her oxygen supply was cut off.

Last November, as I wrote in this column, the United Nations warned of a “perfect storm brewing” which could result in a famine in Rakhine State in which two million people are at risk of starvation.

Without urgent action, nearly the entire population will, according to the U.N., “regress into survival mode”. They are facing “total economic collapse”.

That humanitarian crisis in one region of Myanmar is now compounded throughout the country as a result of the US aid freeze.

Refugees on the Thailand-Myanmar border are now even more vulnerable than ever, with sick children unable to access a doctor and the basic human rights of already extremely vulnerable people now facing an existential crisis.

At least 3.4 million people in Myanmar are displaced as a result of the military regime’s offensives, and the real figure is likely to be even higher. Around 40% of them are children. All are impacted by the U.S. aid freeze.

Elsewhere, many groups championing human rights in Hong Kong, for example, are suddenly faced with having to pause their work. So too are those who campaign for the Uyghurs or Tibet or human rights in China.

This all leads to real concerns that the U.S. freeze on aid will only benefit China, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region but also in Africa and Latin America, where China has already established a foothold to fill a vacuum.

The benefits to Beijing are two-fold.

As the Trump administration freezes funding to Southeast Asian initiatives, Beijing is already increasing its support. And that will be a clear setback, both for lives on the line and for the defense of human rights.

It reduces US soft power and increases China’s influence and the growth of its power, hard and soft. And as the U.S. freezes funding to civil society groups, media freedom initiatives, religious freedom projects, human rights defenders and pro-democracy movements, it undercuts the ability of the US — and the free world — to champion and defend the values on which our civilization has been built, emboldening repressive, tyrannical, authoritarian regimes and leaving those brave activists across Asia and the world, who champion freedom in their own countries, extremely exposed and vulnerable.

It is a grave foreign policy mistake which cannot be in the interests of the United States or the free world, and must be rapidly reversed.

The 90-day freeze was unnecessary, thoughtless, heartless and profoundly dangerous. A legitimate and much-needed review into corruption or spending priorities could have been conducted without plunging millions of vulnerable people into jeopardy and undermining the fundamental values of the free world.

I hope that U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio — who has a long, distinguished and admirable track record of championing human rights and freedom for many of the world’s most persecuted people — will find a way, as the ‘acting director’ of USAID, to restore funding to those most in need urgently, to review and reform the U.S. aid budget quickly to ensure that funds are well deployed and well spent, and to ensure that the United States returns to being the world’s champion of freedom and human rights and the most generous donor to the world’s most vulnerable people, while rooting out corruption, eliminating misuse of funds and focusing USAID on those who need it most: those who depend on aid for survival, and those who deserve our funding for their tireless and courageous defense of freedom.

*The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of UCA News.

Democratic Karen Benevolent Army hands over 261 trafficking victims from 19 countries to Thailand

The Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA) handed over 261 foreigners from 19 countries, who were trafficked into Myanmar to work at cyber scam centers in Karen State, to the Thai army on Wednesday.

The DKBA dismissed allegations of human trafficking into cyber scam centers in Payathonzu town, also known as Three Pagodas Pass, in Kyain Seikgyi Township of Karen State on Monday. Payathonzu is located 143 miles (230 km) south of the state capital Hpa-An and next to Nong Lu in Kanchanaburi Province of Thailand.

It issued a notice on Sunday instructing Chinese nationals “illegally” residing and working in DKBA-controlled territory to leave by Feb. 28.

“I have not seen any Kokang Chinese nationals involved in scam activities in Payathonzu. Some arrived after the battles in Laukkai and Lashio. These people are known for their involvement in gambling activities,” Saw Ae Wang, a DKBA tactical commander, told DVB.

Over half the 261 foreigners released into Thailand by the DKBA on Feb. 12 are reportedly from countries in Africa or Asia. The Thai authorities are currently assessing whether they were, in fact, human trafficking victims.

“Thai people always come to China and feel at home, so I hope that Chinese people can come to Thailand and feel at home as well,” Thailand’s Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra told China Daily during a visit to Beijing last Thursday.

The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) stated that over 6.3 million Chinese tourists had visited Thailand this year up to Dec. 8, making China the largest source of visitors.

Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra pledged to dismantle scam centers along the Thailand-Myanmar border during her meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping last week.

“The problem will not end unless its root cause is tackled,” said former Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, Paetongtarn Shinawatra’s father and the de facto leader of her ruling Pheu Thai Party. “If the scammers are booted out of the country, we will resume the supply of electricity and internet signals,” he added.

The DKBA is not the only ethnic armed group accused of human trafficking into cyber scam centers along the Thai-Myanmar border. The Karen State Border Guard Force (BGF) is also accused of human trafficking and forced labour at cyber scam centers located in BGF-controlled areas, which includes the casino complex of Shwe Kokko.

Prosecutors from Thailand’s Department of Special Investigation (DSI) Human Trafficking Crime Bureau have requested arrest warrants for the BGF leaders, including Saw Chit Thu, Saw Mote Thone and Saw Tin Win.

“The people who came here didn’t just fall from the sky; they were mainly individuals who traveled through Thailand,” Saw Chit Thu told DVB in an interview this week.

“I’ve been at the Thailand-Myanmar border for over 30 years. I’ve helped Thailand many times before. If they want to arrest me, I want to know under which laws they intend to do so,” he asked.

Thai media reported that the DSI received evidence from an Indian national who was rescued after being trafficked and forced to work at a cyber scam center in Myawaddy Township of Karen State.

Prosecutors have advised the DSI to gather additional evidence. Mywaddy is located 80 miles (128 km) east of Hpa-An and is next to Mae Sot in Tak Province of Thailand.

The Royal Thai Police (RTP) announced on Wednesday the formation of a committee to investigate five senior Thai police officers who were transferred from Tak Province, which is located along the Thai-Myanmar border, to Bangkok for alleged links to human trafficking into cyber scam centers in Myawaddy from Mae Sot.

Thai Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Phumtham Wechayachai has rejected accusations from the regime in Naypyidaw that “other countries” – a veiled reference to Thailand – is to blame for the proliferation of cyber scam centres along the 1,501 mile (2,416 km) long border.

He stated on Wednesday that BGF leader Saw Chit Thu will be arrested if he enters Thailand. The Thai government does not seem to be pursuing arrest warrants for DKBA leaders.