Ten years ago today, two of the earth’s largest sub-layers of lithosphere – the Eurasian and the Indo-Australian tectonic plates – rubbed shoulders. The contact sent a shudder 1,000 miles up their common spine, from the epicenter off the west coast of Sumatra to the Nicobar Islands lying remote in the Andaman Ocean, through Burma’s Mergui Archipelago and into the Bay of Bengal.

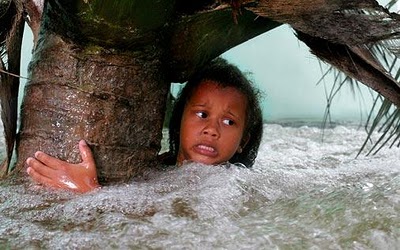

It was early in the morning and few people felt anything. Within 30 minutes the tide had receded 100 meters from the coastline in Sumatra due to the suction of the impact. An hour later it did the same in western Thailand. Fishermen puzzled as to why their boats were suddenly beached, while their wives grabbed a basket and quickly took advantage of the exposed crabs and molluscs along the shoreline.

In southwestern Thailand, thousands of tourists were awakening after a hearty Christmas dinner the night before. Some waded out to sea, others lay on the beaches of Phuket or Khao Lak.

Perhaps 10,000 Burmese migrants were working in that area when the tsunami hit. Many would have been nearby the coast, working as construction workers at holiday resorts, chambermaids in hotels, labourers, fishermen and agricultural workers.

The 1,000-mile rupture ran south to north, forcing waves to the west and east. The western seaboard of northern Indonesia and southern Thailand were devastated. Within 24 hours, at least 226,000 people had been killed by the ripple effect of that 8.8-magnitude earthquake, more than half in Banda Aceh in northwest Sumatra, but thousands of others as far away as Sri Lanka and Somalia.

According to seismologists West, Sanches and McNutt, writing in Science Magazine, the tremor caused the entire planet to vibrate as much as 1 cm and triggered other earthquakes as far away as Alaska.

The Burmese military government – pathologically driven to distort facts and figures of any event at that time – claimed 61 lives were lost in the country, all of whom were fishermen and islanders. In the years ahead, non-government studies would increase the accepted number to around 600.

In Thailand, more than 8,000 perished – 5,395 confirmed dead and 2,932 missing. More than 2,000 of the total figure are known to be foreign tourists, many of them Swedes and Germans – mostly package tourists, staying at beachside hotels in the resort of Khao Lak, which was hardest hit, with waves reaching 10 meters.

But while foreign embassies rushed to help families identify loved ones, and provide flights home to those affected by the tsunami, Burma’s pariah government remained mute.

The Burmese victims were invariably working illegally, and their surviving relatives were often too afraid of imprisonment to come forward to identify remains. It is only years later that Thai officials and migrant assistance organisations can cast a final guess at the number of Burmese deaths – through process of elimination – to be about 2,000.

Of that number, there are arguably hundreds of bodies that were recovered but are yet to be identified.

Of the nearly 4,000 bodies where DNA and data was taken in Thailand, 369 have yet to be claimed. The remains of those 369 people are currently interred at Bang Ma Ruan cemetery in Phang Nga, the closet town to Khao Lak, situated just north of Phuket island. It is with a fair degree of certainty that most of these souls are Burmese.

Unless the victims had no living relatives, it stands to reason that someone would come forward after a period of time, realising that their family member had not returned from working abroad or from holiday. Although Thailand also has a great many illegal migrants from Laos and Cambodia, very few of them work in southwestern Thailand; cheap labour is almost exclusively from Burma.

I was a stretcher-bearer in Khao Lak in the wake of the tsunami, meaning I had volunteered to carry corpses on stretchers within the temple grounds where forensics teams were tagging them and distraught relatives were taken to identify them. It was a harrowing experience.

In effect, I was part of the chain that collected, identified, segregated and tagged each of the victims which were retrieved.

Like hundreds of others, I had traveled to Phuket to volunteer. The first thing that hit me when I got off the bus was the number of “missing” posters nailed and sellotaped to every available wall space.

[related]

I was meeting a group of volunteers from Chiang Mai and we headed in a pick-up truck to Patong Beach. It was a hot day: 29 December. The sea was crystal clear. The beach was pristine and the sand was white. Most palm trees were still standing. But behind the promenade the scene was like Hiroshima. Everything was down: hotels, bars, restaurants. It was all just rubble mixed in with the occasional everyday object – a chair, a parasol, a shoe.

Two cars had wedged together between a garage and a restaurant. They looked as if they had been interrupted in mid-flight. A local man told me that they had to pry four bodies from that wreckage the other day.

Khao Lak was destroyed beyond recognition. A coastguard boat – about 30 metres long – had been dragged in on one of the waves and had ploughed over a cliff and landed in a forest some 800m from the beach.

I was assigned to Wat Yang Yao, the main temple in Khao Lak, and the focal point for all the forensics work. I was kitted out in rubber boots, a cape, rubber gloves, a shower cap and as many face masks as I needed. As soon as I entered the restricted area which was acting as a makeshift morgue, it was like landing on a different planet. I took the arms of one end of a stretcher and helped fill it with blocks of dry ice. We carried the ice into the temple grounds and laid them on the corpses, some of which were in body bags, others exposed. There were hundreds of bodies. Everywhere. As far as you could see.

I’ve heard it said that drowning is a nice way to die; the brain slowly shuts down and you drift away, something like that. Unfortunately I do not believe that many of the dead people I saw had drowned. They were battered to death – thrown into a giant washing machine with cars and fishing boats and concrete walls. I would like to believe that their souls departed their bodies quickly and peacefully, not tortured as their flesh and bone was.

Let me explain the process for the recovery of bodies. Many of the tsunami victims had been lost at sea for several days. If they had been floating, then rigor mortis had set their bodies into a horrific spread-eagled position. Men tend to float face up; women float face down due to the distribution of weight in their hips. By New Year’s Day, that position was often the only way to tell them apart, so decomposed and ravaged were the remains.

The bodies were collected by Thai rescue teams who combed the beaches, swamps, ruins and forests. Bodies were bagged and transported one by one to the morgue or a Buddhist temple. The trucks were met by stretcher-bearers who carried the corpses to a designated area (say Area A) where they are laid out on the ground on plastic sheets. In one day, over 1,000 bodies arrived, one truck after another. Stretcher-bearers would also carry dry ice back and forth and place it on top of the bodies.

Forensic teams worked one corpse at a time, around the clock. The stench alone would make you retch constantly. The doctors test the corpses in Area A to detect whether he or she is Asian, European or other race. Hair follicles and teeth are examined and, when identified, the corpses are then carried to Area B or C or D, depending on race; then separated again into males and females; adults and children. Burmese and Thais, therefore, were placed together.

Sometimes the results of the DNA tests were inconclusive, for instance, if the victim were a Eurasian. Then there were other teams who began the process of identification by photographing the dead. Any tattoos, rings or necklaces were collected and placed with the corpse in a photograph which was put up on a website for bereaved families to study at Phuket Hospital.

At the wat where I was posted, several days had already passed since the tsunami and therefore bodies were being cremated as soon as they were positively identified to prevent disease. Unclaimed bodies were kept “on ice” for a certain length of time, then tagged and buried in case they were identified at a later date.

Ten years later, just 369 bodies remain. It is not unusual for Burmese who migrate, especially rural folks, to disappear from home for years at a time. Few would have had access to Internet in 2004 and general post was considered unreliable. Mobile phones were not as prevalent among migrants as today.

“I recommend that those relatives still searching for tsunami victims to contact the 8th Region Police Office directly and bring as much information as they can, such as dental records, to match with the bodies in Bang Ma Ruan, Thailand’s Pol-Col Yutaphong has been reported saying recently.

Nowadays, Burmese migrants have the opportunity to register as foreign workers in Thailand. It may therefore be prudent for the Burmese government to use this 10th anniversary as an opportunity to appeal to families whose relatives went to Thailand and were never heard from again. Perhaps many of the 369 unclaimed bodies could be identified.

So, what lessons have been learnt since 2004? First, we are all suddenly experts in tsunamis, a word most of us never even knew before. Only a few persons at the scene of the disaster in western Thailand are known to have recognised the signs of an incoming tsunami – a biology teacher from Scotland, who evacuated tourists from Kamala Bay on Phuket, and a 10-year-old English girl named Tilly Smith who reportedly studied tsunamis in geography at school and remembered the warning signs of receding tide and frothing bubbles.

The Moken, or sea gypsies, also knew about the pending doom through folk tales. Many of them were instrumental in saving lives in the minutes and hours after the waves struck by sailing beyond the swell, then returning to pluck stranded victims from the water.

Today the Indian Ocean is peppered with tsunami warning systems. Some have proven to be faulty – in 2012 an 8.8-magnituade quake struck again off the coast of Banda Aceh, but the sirens remained silent.

Burmese migrants helped in the rebuilding of the resorts on the Thai coast and tourism is now flourishing again. The greatest danger on Phuket these days would seem to be the local taxi mafia. Resorts, hotels, bars and restaurants all vie for the prime real estate in front of the beach.

Today local knowledge includes a fear of tsunamis. Millions of people around Asia and Africa can now rely on first-hand nightmares to remind themselves and their children of what to do and where to run if the sea suddenly recedes and water froths in the tideline.

And many people will never look at the ocean the same way again.