By Sippachai Kunnuwong for Fortify Rights

On January 20, 2023, Fortify Rights and 16 individual complainants from Myanmar filed a criminal complaint in Germany under universal jurisdiction against senior Myanmar military officials and others for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. This article is part of a four-part series profiling some of the complainants.

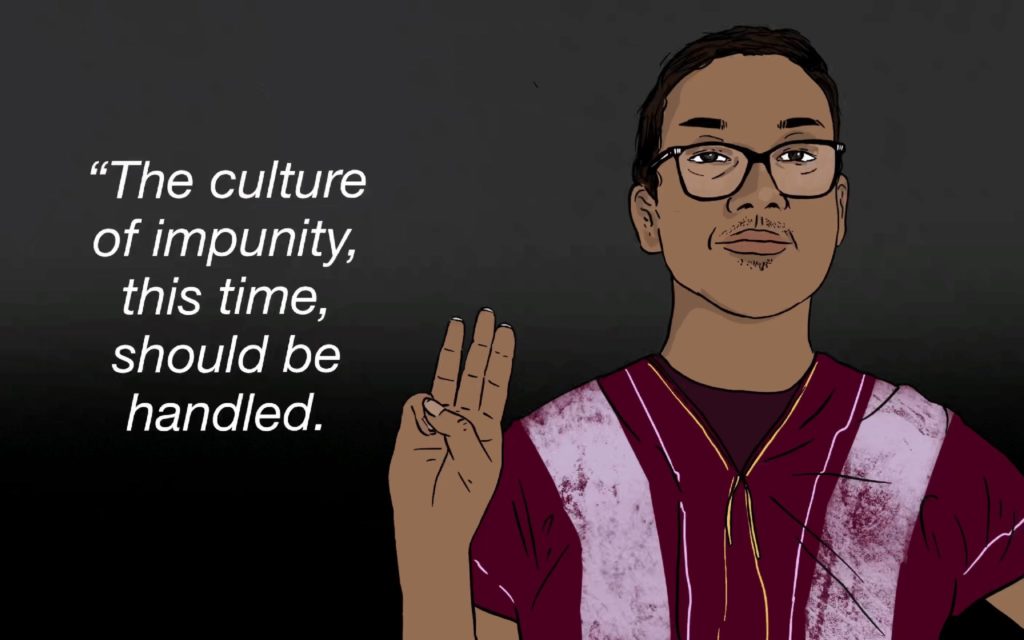

(BANGKOK, January 25, 2023)—Nickey Diamond, 39, is no stranger to the dangers of human rights work. Originally from Mandalay in central Myanmar, for many years his investigations into violations against the ethnic-Rohingya population and others in Myanmar led to death threats and other well-founded fears of persecution.

Since a military coup d’état on February 1, 2021, followed by the military’s deadly attacks against civilians nationwide, the risks he faced intensified. In 2021, the junta added Nickey to a “capture list” for his work.

“After the coup . . . I was told [by contacts in the Ministry of Home Affairs] that if I was captured, I would most likely be tortured and/or killed,” Nickey told Fortify Rights. “Around March 10, 2021, my family and I escaped.”

Now in Germany with his family and two young children, Nickey’s work continues.

“German people have real-life experiences as we do in Myanmar.”

On January 20, 2023, Nickey, 15 other survivors from Myanmar, and Fortify Rights filed a 215-page criminal complaint in Germany requesting the German Federal Prosecutor General to open an investigation into genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes committed by the Myanmar military.

While mounting evidence proves that the Myanmar military is responsible for committing atrocity crimes that continue until today, not a single perpetrator has been held accountable.

Germany’s has one of the world’s strongest “universal jurisdiction” laws, making it possible for German authorities to investigate and prosecute grave international crimes happening around the world, including in Myanmar.

Nickey reflected on the critical role Germany may play in advancing justice for Myanmar’s many victims and survivors.

“Germany has a dark history of the Holocaust,” Nickey said. “German people have real-life experiences as we do in Myanmar. If [the German authorities] accept the case and open the investigation, that would be a huge success.”

“She couldn’t get the remedy.”

Nickey grew up in a Muslim family in Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city.

In a Buddhist-majority country with a long history of anti-Muslim sentiment, Nickey said he experienced “bureaucratic” and other forms of discrimination throughout his life:

One of the biggest challenges for Muslims is citizenship. When I was 10-years old, I got what they called a “10-year-old” card…When I turned 18, I could get [a citizenship card]. When I was 18, I applied for citizenship. Because I’m a Muslim…the immigration officer asked me for a bribe. But I didn’t want to pay. So, it took me seven years to get my citizenship card.

However, his political awakening didn’t begin until the traumatic death of a college friend in Myit-Nge town near Mandalay in central Myanmar, as he recalled:

One day when she was farming, she was bitten by a poisonous snake. She couldn’t get the remedy. Her parents sent her to the nearest clinic, but they didn’t have a remedy or cure because it must be [stored] in a refrigerator. But the clinic didn’t have electricity. She was then sent to another public hospital. On the way to the hospital, she passed away.

Nickey blamed the loss on an incompetent government: “This is an area famous for snakes. They must provide some kind of action to help with these kind of situations. This kind of trigger drove me to become a human rights defender…to figure out how I could contribute to my community and society.”

“The victims and survivors were not alienated.”

Nickey’s first social activism began in 2007 when he founded the Youth for Social Change Myanmar (YSCM), a non-profit providing alternative education to impoverished youth. The project was inspired by his own struggle with Myanmar’s educational system.

“After my high school graduation, I believed that I couldn’t get a quality government education,” Nickey told Fortify Rights. “So, I went to the library and educated myself . . . We had a kind of social-study group at many libraries. Every week, we read one text and tried to understand [an] argument and discussed and shared our thoughts. Later, I thought this is a good practice [and] should be franchised, reaching out to other communities in different parts of the country.”

Then came military-led attacks against Rohingya-Muslim civilians in 2012, and then anti-Muslim violence by Buddhists in Meiktila in central Myanmar in 2013, making Nickey rethink his career path.

“I was disappointed to see people crossing their [moral] lines, killing people purposely,” Nickey said, adding that he spent the next few years in Thailand working toward a master’s degree in human rights.

In 2015, Nickey joined Fortify Rights as a Human Rights Specialist, where he continued to investigate and document violations committed by the Myanmar authorities against Muslims as well as support communities affected by violations.

Elaborating on his human rights work, Nickey said:

At Fortify Rights, I maintained my relationships with the victims and survivors. Whenever human rights violations happened, we would conduct research and interview. . . . They called me and updated me on what their situations were. I feel like the victims and survivors–the people on the ground–were not alienated.

“Because of our engagement in the affected community, we have the privilege to access the information regarding the new situation and issues…we can talk to the media and let the world know what happened to [these communities],” he added.

This work came with risks.

“I received death threats most of the time when I was working [with] Rohingya and victims of Meiktila. At the time . . . talking about or defending the rights of marginalized people in Rakhine and other parts of the country was very dangerous. But I had an [intelligence connection] in the military . . . He [gave me] early warnings–[advised] what I should do or shouldn’t do.”

But following the 2021 military coup, Nickey shared how the situation shifted: “There were no rules and regulations or rule of law. [The authorities] not only wanted to arrest me but also [wanted to] kill me.”

“The culture of impunity, this time, should be handled.”

Nickey is now on the Board of Directors at Fortify Rights and studies anthropology at a German University, focusing specifically on anti-Muslim hate speech in Myanmar and its link to the persecution of Muslim communities.

He also continues his activism—giving talks and campaigning for democracy and human rights—despite his frustration that “international accountability and justice [is taking a long] time.”

However, he remains hopeful about the prospect of a criminal complaint in Germany against the junta officials and others, explaining:

Some [Myanmar military and junta officials] in the targeted list have visas in Europe and frequently travel there. If Germany receives the case and opens an investigation, [when the authorities] issue the warrant [against them], we can arrest some of them for prosecution . . . This could be one option to press the European Union and other European countries on Myanmar.

He added: “[The previous civilian government in Myanmar] didn’t pay attention to transitional justice, so the military has been doing whatever they like given the strong culture of impunity [in Myanmar]. But the culture of impunity, this time, should be handled.”

Sippachai Kunnuwong is a Communications Associate with Fortify Rights. Follow him on Twitter @10pachai.