A ban on all raw timber exports from Burma came into effect on Tuesday, in an attempt to rein in one of the country’s highly lucrative and notoriously corrupt extractives. The new regulation, which criminalises cross-border trade of unrefined wood products, is meant to stop the flow of raw resources and encourage development of value-added processing industries, though many are sceptical of the government’s ability to accomplish that outcome.

“The main issue with the log export ban at this stage is the lack of state and private-sector support in establishing a more robust wood processing sector in the country,” said Kevin Woods, a researcher for the environmental rights group Forest Trends. Woods is one of many resource experts concerned that the ban could reinforce corruption in one of the country’s most opaque industries while doing nothing to moderate exploitation.

The government has not put forth any plans to increase processing industries, which according to researchers opens two possibilities: if in-country processing remains unsupported and undeveloped, illegal trade could actually increase in richly forested border areas; if the industry is concertedly developed, what is already known to be a state-owned monopoly could simply expand into even more businesses.

“No one has seen any official paperwork outlining the ban,” said Faith Doherty, Forest Team Leader at Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a UK-based environmental rights group that accused the government last week of complicity in illegal trade of timber.

“The Government’s official data on forestry and timber exports reveals endemic illegal logging and timber smuggling – crimes only possible through institutional corruption on a huge scale,” read a statement accompanying a report that examined government export records against imports documented by other nations. The data indicated a fiscal “black hole” amounting to US$6 billion worth of wood.

“Burma has absolutely no transparency within the sector,” said Doherty, upon DVB’s inquiry as to where the money could possibly be. “With US$6 billion unaccounted for, your question should be addressed to the government. We don’t know.”

[related]

The inquiry had, in fact, been initially directed to both Burma’s Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (MOECAF) and the managing director of the Myanma Timber Enterprise (MTE), neither of whom offered any explanation. The Ministry of Commerce also declined to comment.

The extent of corruption in Burma is “really quite stunning”, said Sam Zarifi, regional director of the International Commission of Jurists. Literally every sector, he said, is and will for some time remain dominated by government cronies, especially in the booming extractive sector, where profit margins are high.

Figures reported by EIA dealt only with recorded materials; much of the massive count of illicit timber was traded under the supervision of the MTE, which is a state-owned company established in 1989 to oversee all logging concessions and manage trade.

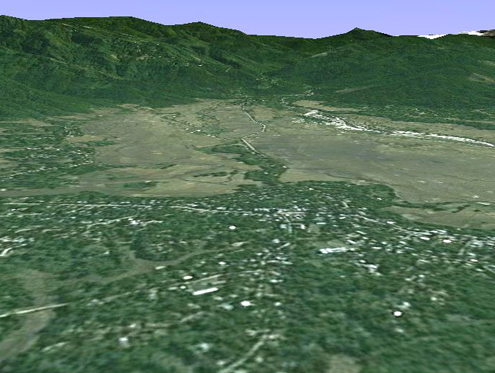

This means that much of the unauthorised trade occurred in areas controlled by the central government, and the numbers don’t even begin to account for logs traded in Burma’s many ethnically manned border regions, which frequently act as a conduit for illicit cross-border movement to China. In Kachin State, for instance, the illegal export of logs via the Burma-China land border has been estimated to bring in more than US$200 million per year, much of which is thought to fund rebel army operations. A recent visitor to the Sino-Burmese border said he observed a “constant stream of trucks” carrying logs from Sagaing Division to China via Kachin State, noting that “there’s very little old growth left in the Kachin hills thanks to the massive levels of logging that took place over the past decade”.

Deforestation is an added complexity to Burma’s logging problem; the new rules target commerce, but they don’t directly curb the rapid decline in forested lands. Estimates vary, but most environmentalists agree that during British colonial times some 80 percent of the country was wooded, diving to 60 percent in the 1960s. Deforestation accelerated under military rule, and government figures put Burma’s current forested area at around 47 percent, though some officials have offered lower estimates.

“The log export ban doesn’t mean much for actual logging, but rather what you do with the logs after you have them,” said Woods, explaining that while the ban could lead to decreased demand — if implementation stalls deliveries, for example — it is not, as some think, going to preserve Burma’s forests. The Burmese government has, however, committed to lowering its annual allowable cut (AAC) for teak and other hardwoods, which could bring some wins for preservationists.

Those successes could be very meaningful in Burma, where many still rely on the forest for basic needs like food, shelter and safety. Moreover, Woods suggested that the disappearance of both trees and vital non-timber forest products (NTFPs) can lead to all manner of consequences, for instance, scarcity of firewood and coal means that women travel longer distances to collect. In Burma’s extreme but real circumstances, “there is increased chance of rape, especially in conflict-prone areas.”

While the raw timber export ban is one step towards avoiding a regrettable transformation in one of Burma’s major industries, it may only work in tandem with additional reforms meant to tackle the country’s deep-seated corruption. The Burmese government has, at least, acknowledged the problem by committing to measures like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and forthcoming preparations to join the EU’s Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT) initiative, but has not yet proved the ability or the will to enforce violations.

“That’s, of course, the billion dollar question,” said Zarifi, emphasising that new media freedoms offer Burma’s strongest anti-corruption tool. Monitoring the logging and timber industries will largely be a task for journalists, activists and citizens, because information that incriminates cronies is unlikely to come from the government.

“Right now, that judicial capacity and that political will is quite low.”