Lu Kyaw for Reporting ASEAN

I get so angry when someone calls me ‘a soldier’s wife’. I don’t want to hear those words anymore. I don’t want to be connected to that community [military] anymore,” Ma Aye said, visibly irritated.

For most of her life and until the February 2021 coup in Burma, Ma Aye was part of the country’s military community. Her father had been a private assigned to the army infantry, and she herself married a soldier. Her childhood days were spent with other youngsters, like her children of rank-and file members of the armed forces.

But these days, Ma Aye is a teacher in Burma’s central dry zone, in an area controlled by the National Unity Government (NUG), the country’s parallel government that was formed after the junta, called the State Administrative Council, seized power.

Her husband, who was a warrant officer who designed military barracks for the armed forces, has been fighting the military junta’s troops as a member of a local People’s Defence Force, units that have been in armed conflict with the junta across Burma. The couple’s two adult daughters are in the security unit of the local PDF group.

“I am happier (now) because my two daughters are revolutionaries. I am proud of them,” 43-year-old Ma Aye said, her Burmese accent reflecting her roots in Sagaing region.

Life has been far from easy since her family left the military and joined the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) in June 2021, four months after the coup. But, she added, “I don’t worry about my daughters. Whether we live or die is according to our karma. Whatever it is, death for the revolution is a holy death.”

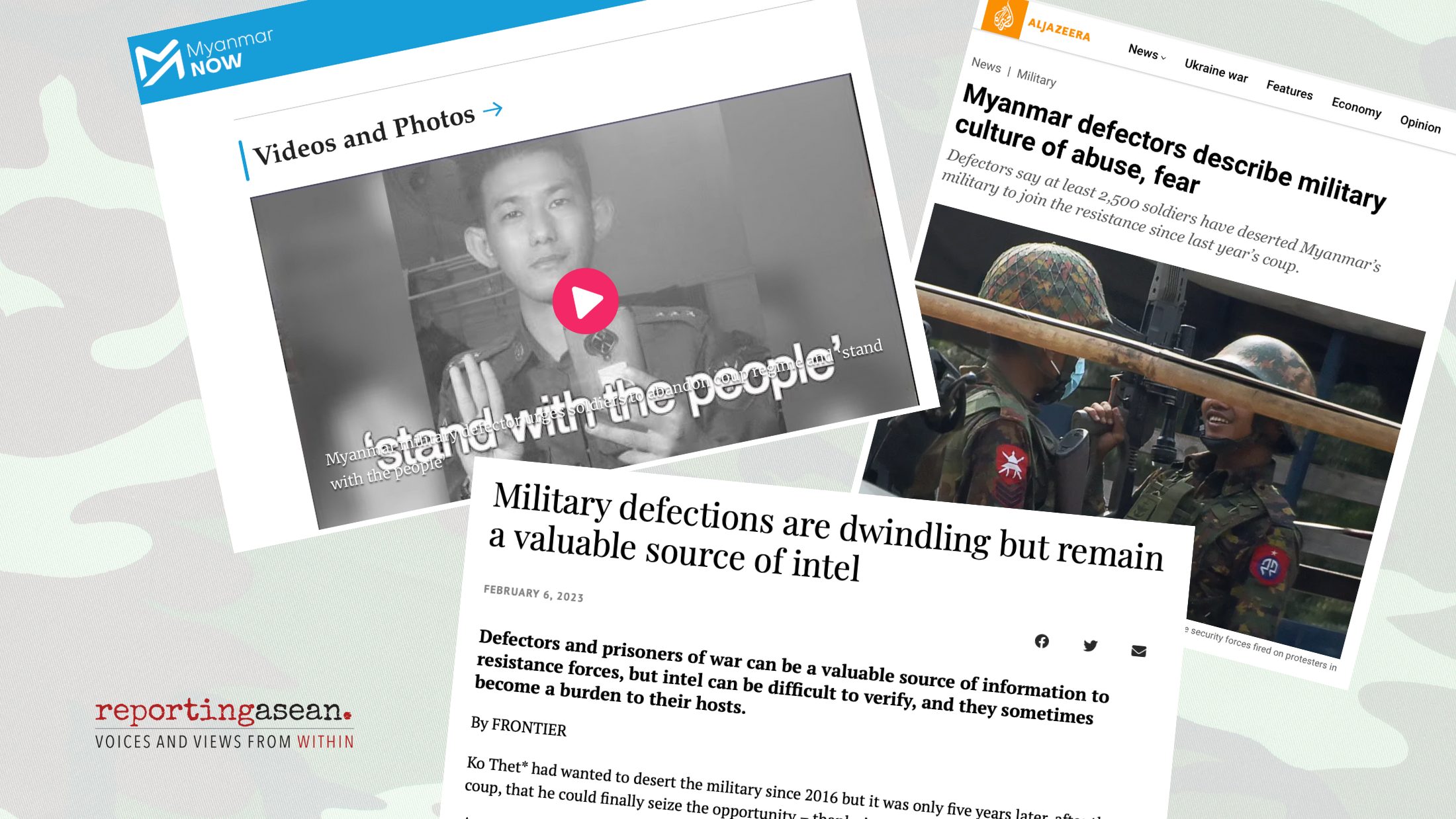

Estimates of how many soldiers have deserted and left the military, or joined the anti-junta resistance, are hard to come by. People’s Embrace, a group formed by military defectors, says 8,000 troops left in 2021 but that this had fallen to 2,000 from January to October 2022, according to a February 2022 news report by Frontier Myanmar. By another count, the NUG said in April 2022 that more than 3,000 soldiers had joined the CDM since the coup, Myanmar Now reported.

“I am happier (now) because my two daughters are revolutionaries. I am proud of them,” said 43-year-old Ma Aye, whose husband defected from the military in 2021.

The most common estimates put the military’s size at 300,000 personnel, in an institution that sees itself as the force that has held the nation together since independence in 1948. Various military regimes have ruled the country through the decades, except for the decade of political transition that started in 2011 and was cut short by the military coup.

A state within a state, the military is known to be corrupt, pay soldiers poorly and force troops to invest in military companies. Over decades, its human rights atrocities have documented by independent groups. It has also sought to firmly control its personnel and their families.

RANK ISN’T JUST FOR SOLDIERS

Accounts by those who have left the armed forces, like Ma Aye and her family, offer a peek into its culture. Rank, privilege and power are levers that operate not only within the military structure, but extends to the spouses of soldiers and their children.

“They discriminate according to the position of the parents,” Ma Aye recalled. “Most of the children of officers discriminate against us [children of rank-and-file soldiers].”

Officers routinely require subordinates and their spouses to provide ‘services’ – for free – to personal businesses and households. Ma Aye’s mother had to do domestic work for her husband’s superiors, and her husband had to do tasks for his officers’ businesses.

Moreover, on the days when she went to do this forced labour, “my mom had to bring food not only for herself but for the officers and their families,” Ma Aye said. Her mother also ‘helped’ in tending to the chicken and other animals in officers’ households.

At one point, she says, her father was physically beaten and called “useless” when he could not raise some amount of money for the army that his officers wanted him to raise from business deals on farming, among others.

Her parents’ experiences made her long for a life outside the military. After her father’s death, Ma Aye welcomed the chance to move away from military circles. Military families like Ma Aye’s give up their housing after their enlisted member passes away.

Ma Aye continued her studies, and got her university degree. A man she met at her graduation rites – a classmate’s friend – later became her boyfriend. She had resolved to cut ties with the military, but learned that the man she was dating was a private in the engineering infantry.

“I thought that I didn’t want to marry a soldier, but I was falling in love with one. This disturbed me,” she recalled, adding that she eventually learned to accept this. After they got married, Ma Aye was back to living in military housing – and to the culture she had wanted no part of.

Her husband’s pay at the time, around 2006, was just 20,000 Burmese kyat or about $20 US dollars. While military personnel get rations such as low-quality rice and sugar, these were inadequate. Like many others, her husband needed to make other income, such driving motorcycle taxis and being a real estate broker for modest houses in his free time.

The couple’s children experienced the same discrimination that Ma Aye and her three siblings went through in the past.

“They [children of high-ranking officers] think that only they should have enough to be able to do things – spend money, visit tourist sites, eat good food. The children of officers don’t want to associate with the children of non-officers, so they looked down on our children,” she explained.

A RERUN OF THE PAST

Like her mother, Ma Aye found herself being asked to do domestic work in officers’ homes. She declined and said that she had to look after her children, and her husband also refused the ‘requests’.

“They [officers’ wives] wanted me to serve them like their maid. My husband replied that his wife was a [university] graduate and didn’t need to be a maid,” she recalled. He told them that while he had to “serve as their [officers’] slaves”, his family did not.

The pressure stopped, but the consequences of standing up to military higher-ups were evident. Subsequently, her husband’s superiors did not assign him duties that provided what is called “outside money” – in this case, soldiers’ extra and illegal income from tasks like the construction of buildings and roads. He got passed over in promotions.

During election time, Burma’s military hierarchy demanded that soldiers vote for the military’s political party and proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), Ma Aye says.

“In the 2015 election, we had to vote for them (USDP). The officers forced us to vote for them. They forced us in the 2020 election too. They showed us the USDP logo, and asked us to vote for it. But most of the soldiers and family members in our housing didn’t vote for them,” she said. “So they lost even in the military-influenced townships [where voters are mostly soldiers and their families].”

At the national level, the NLD, led by the now-detained State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, won a landslide victory with 83% of seats in the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, the union parliament. It was the convening of this parliament on 1 February 2021, where the NLD was to form a new government, that the military coup blocked. The USDP got just 5% of the vote.

Despite the military’s refrain about the coup being necessary due to election fraud by the NLD, some soldiers and their family members were critical of the power grab, Ma Aye says. She recounted: “They said the coup was a kind of bullying using arms, but no one dared to criticize openly. They whispered their criticism, talked to each other about this. They said that the coup is not good and shameful.“

Some soldiers’ children took part in the street protests that erupted soon after the coup. When some posted and shared critical views on Facebook, their soldier-parents got warnings from their superiors.

“I have friends on Facebook who support NLD and democracy, but I dared not react, or like their posts. The [soldiers’] children who reacted with likes to the critical posts of their Facebook friends were interrogated at the military office,” Ma Aye said. “They scolded the parents because they couldn’t control of their children. And all of us had to give a list of all the Facebook accounts of our family members.”

Some children from military families joined the anti-coup forces. “Some called my daughter to go with them. They had already bought guns for themselves. They used their own money for these,” she added. “One girl told my daughter that she had two guns, and would provide one for my daughter. My daughter thought about me and didn’t follow.”

In June 2021, Ma Aye’s family left their military quarters, and life in the armed forces, for good. “I didn’t worry for myself [when we left]. But I worried seriously for my two daughters and son, very seriously, especially for my two teenage daughters,” she said.

‘WE MUST WIN’

Joining the resistance was not easy since they came from the military, so it took them several attempts to find a new home in friendly, anti-junta territory.

After making contact with resistance groups, Ma Aye’s family walked for three to four days in the jungle to join them. One night, the truck that they and others headed for safer regions were travelling in, with supplies like bags of rice, was stopped by junta troops. “They asked where we were from, and where we were going. We lied and said we were headed for the monastery to donate meals to the monks the next morning,” she explained.

They eventually reached the village where Ma Aye and her family were warmly welcomed, and where they live today.

Many more soldiers want to leave the military, she believes. “Most of them. But high-ranking officers control them via their families, like kidnapping. So the soldiers worry about their families and dare not join CDM.”

She says that a victory by the anti-coup forces, in a more democratic Burma, should mean having a professional military. Ma Aye said: “We must win. If we win, we can get back our rights and dignity, our lives and all. If we lose, they [military junta] will make us their slaves for decades.”

(END/Reporting Asean/Edited by J Son)